Policy Recommendations

The following measures can play a role in promoting positive family planning and sexual and reproductive

health outcomes in India:

Promoting decentralised planning and

implementation of programmes related to

family planning and sexual and reproductive

health, with focus on local priorities and

vulnerable groups

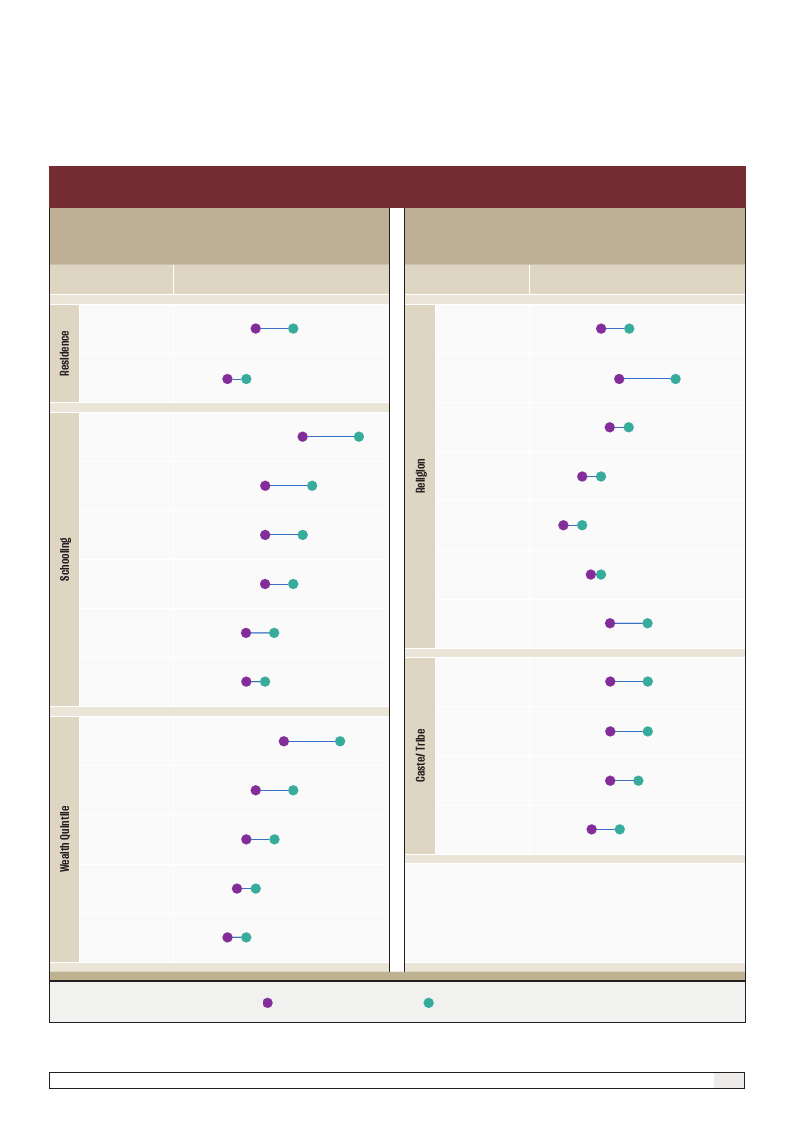

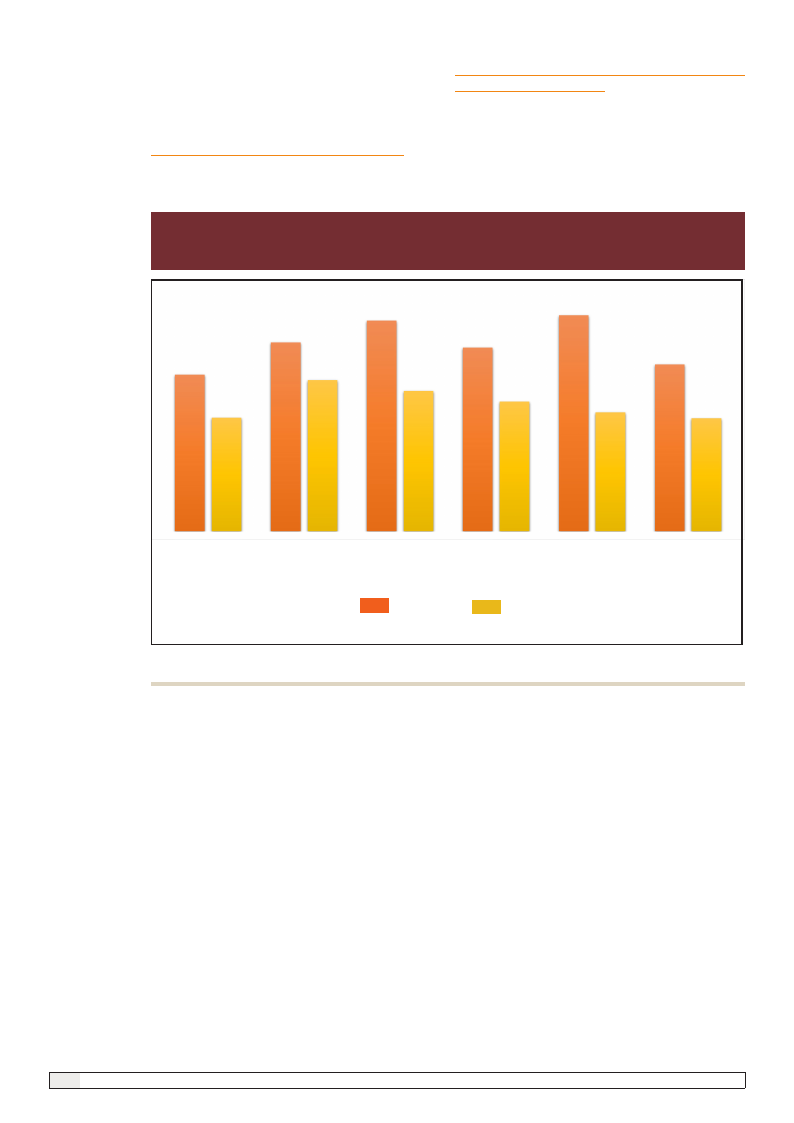

As the data for India shows, there are significant

inter-state and inter-regional variations in

health and fertility outcomes, due to unequal

investments in health infrastructure, education,

women’s empowerment, and overall development.

Consequently, the policy and programmatic

response needs to address systemic gaps at

the local level in the delivery of family planning

and sexual and reproductive health (FP–SRH)

services, so that they are accessible uniformly

across the country. The response also needs to

adopt a convergent inter-departmental planning

and implementation model to address the social

determinants of health and fertility behaviours,

such as girls’ education, gender norms, early

marriage, women’s decision-making autonomy, and

social justice.

Advancing informed and evidence-based

discourse on population issues to dispel

popular myths and misconceptions

needs to be utilised effectively by policymakers

through regular exchanges with researchers, civil

society organisations working at the grassroots

level, and state-, district- and sub-district level

functionaries who implement programmes.

Looking at FP-SRH as a key component

of people’s well-being and sustainable

development

Considering the lifelong and inter-generational

effect of fertility decisions, and their subsequent

impact on the country’s development trajectory,

policies and programmes on FP-SRH need to

be a national priority kept front and centre of

sustainable development strategies, rather than

being a subheading under women’s health. As a

signatory to the ICPD Programme of Action, India

has achieved significant progress in addressing

high population growth through a rights-based

approach to family planning. With the shifting

demographic profiles of states, policies and

programmes have to address the needs of aging

populations in some regions, while increasing

livelihood opportunities in others with younger

populations, and balance population stabilisation

with efficient resource utilisation for sustainable

development.

Survey and research data are the building-blocks

of governance, and India has a robust system

of regular monitoring and evaluation of family

planning programme delivery. This knowledge base

References

1United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022). World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. UN

DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 3.

2The average number of children a woman would have by the end of her childbearing years if she bore children at the current age-specific fertility

rates

3Sample Registration System Statistical Report 2020

4POPULATION PROIECTIONS FOR INDIA AND STATES 2011 – 2036, Census of India 2011

5The State of World Population 2014, UNFPA

6World Population Prospects 2022

7The average number of children a woman would have by the end of her childbearing years if she bore children at the current age-specific fertility

rates, minus unwanted births

8Including those who were sterilised – International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. 2021.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5),

2019-21: India: Volume I. Mumbai: IIPS.

9International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. 2021.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India: Volume I. Mumbai: IIPS.

10Nirmala Buch. Economic and Political Weekly. 2005. Law of Two-Child Norm in Panchayats

11United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2021). Global Population Growth and Sustainable Development.

UN DESA/POP/2021/TR/NO. 2.

India’s Population Growth And Policy Implications

7