|

Infant Mortality Relation to Fertility FPF IDRC |

|

1 Pages 1-10 |

▲back to top |

|

1.1 Page 1 |

▲back to top |

|

1.2 Page 2 |

▲back to top |

|

1.3 Page 3 |

▲back to top |

|

1.4 Page 4 |

▲back to top |

|

1.5 Page 5 |

▲back to top |

|

1.6 Page 6 |

▲back to top |

|

1.7 Page 7 |

▲back to top |

|

1.8 Page 8 |

▲back to top |

|

1.9 Page 9 |

▲back to top |

|

1.10 Page 10 |

▲back to top |

|

2 Pages 11-20 |

▲back to top |

|

2.1 Page 11 |

▲back to top |

|

2.2 Page 12 |

▲back to top |

|

2.3 Page 13 |

▲back to top |

|

2.4 Page 14 |

▲back to top |

|

2.5 Page 15 |

▲back to top |

|

2.6 Page 16 |

▲back to top |

|

2.7 Page 17 |

▲back to top |

|

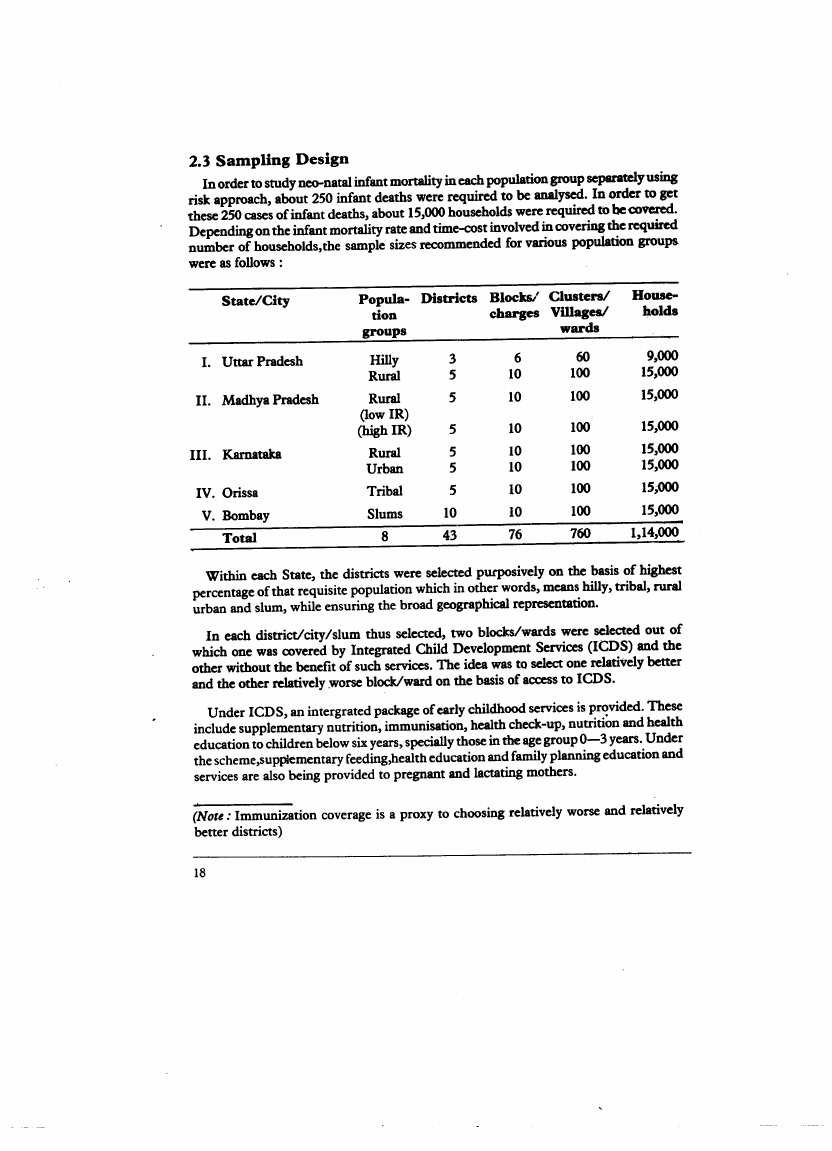

2.8 Page 18 |

▲back to top |

|

2.9 Page 19 |

▲back to top |

|

2.10 Page 20 |

▲back to top |

|

3 Pages 21-30 |

▲back to top |

|

3.1 Page 21 |

▲back to top |

|

3.2 Page 22 |

▲back to top |

|

3.3 Page 23 |

▲back to top |

|

3.4 Page 24 |

▲back to top |

|

3.5 Page 25 |

▲back to top |

|

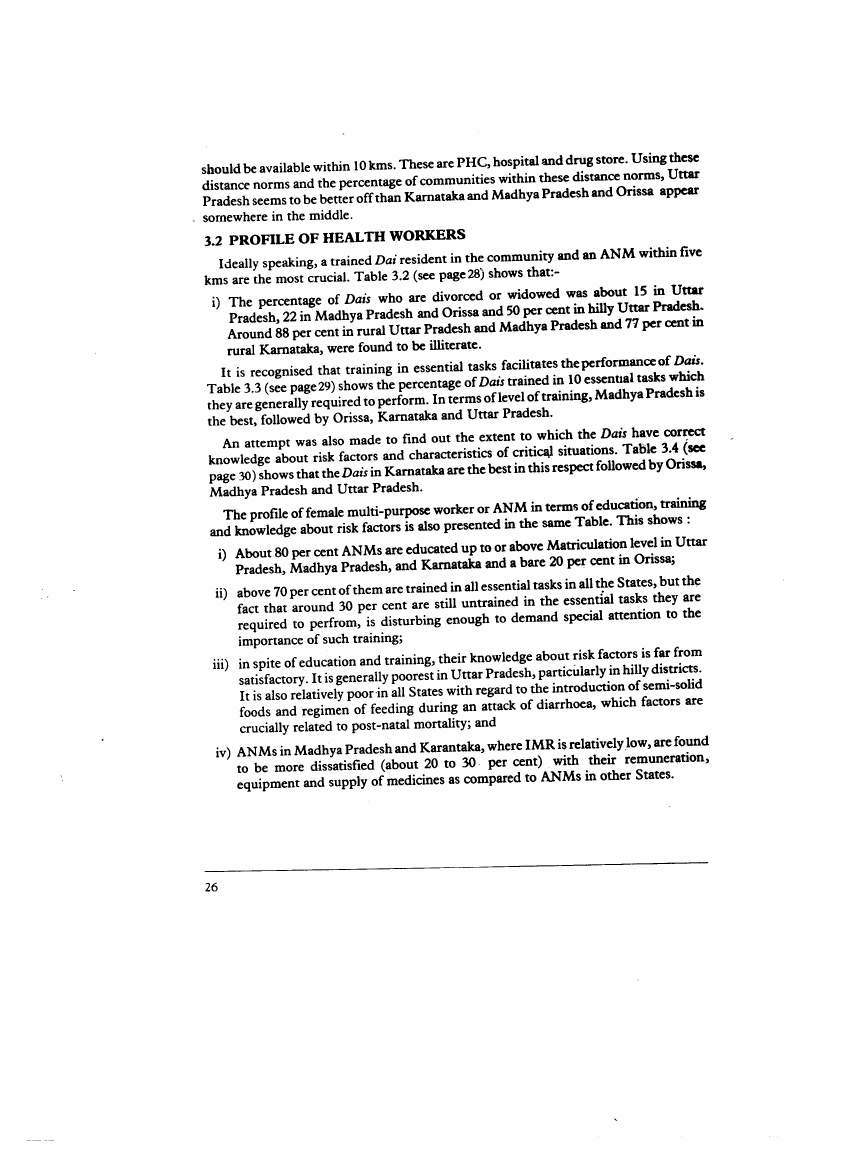

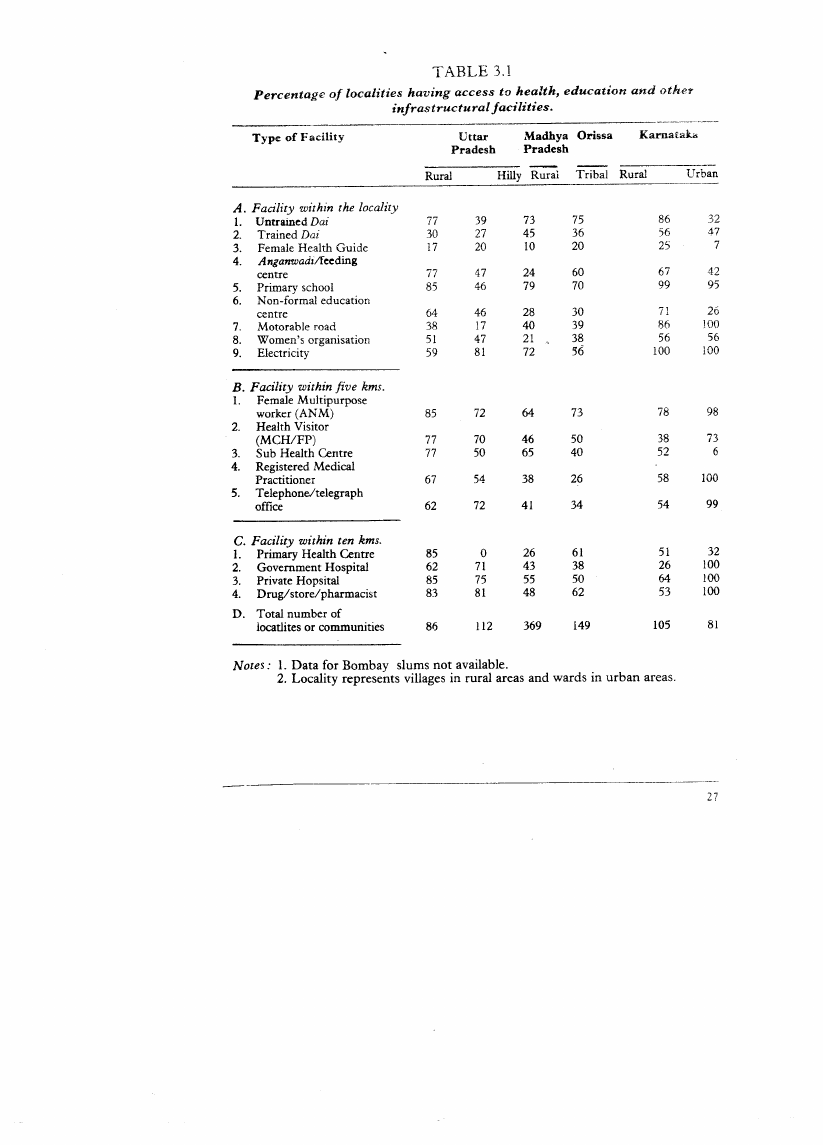

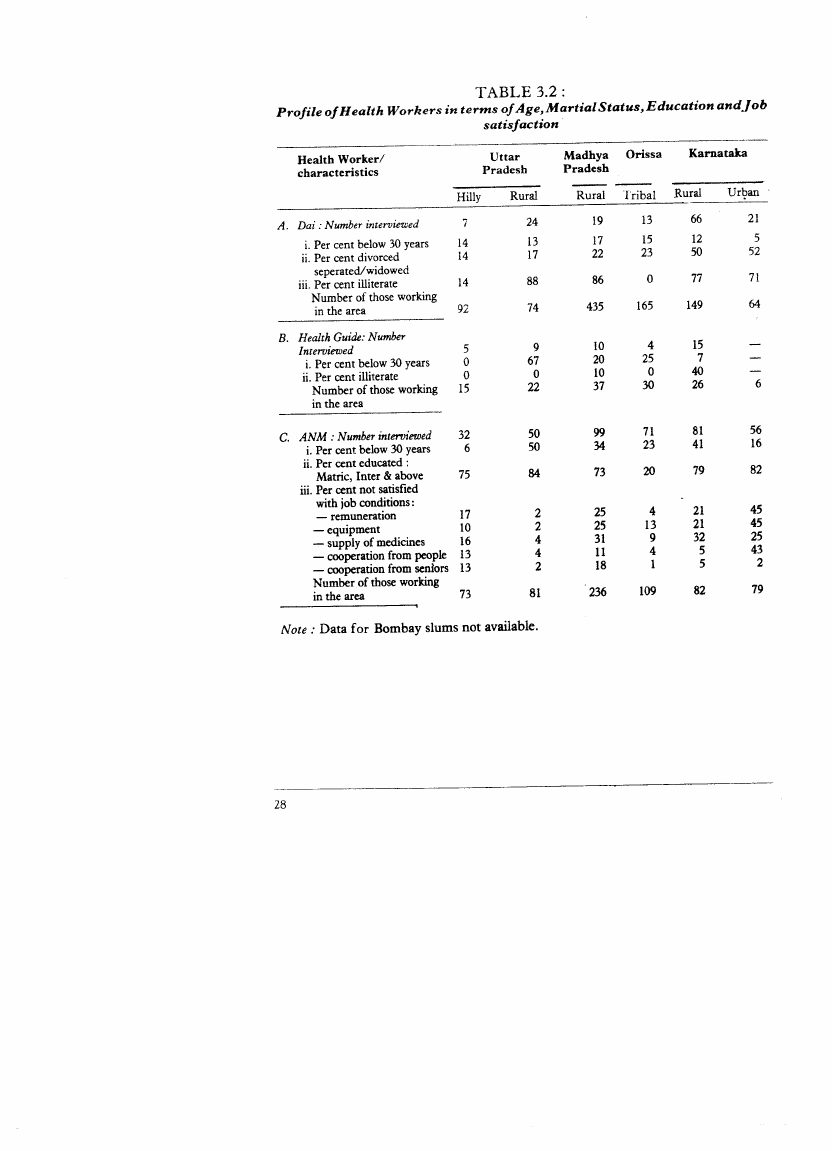

3.6 Page 26 |

▲back to top |

|

3.7 Page 27 |

▲back to top |

|

3.8 Page 28 |

▲back to top |

|

3.9 Page 29 |

▲back to top |

|

3.10 Page 30 |

▲back to top |

|

4 Pages 31-40 |

▲back to top |

|

4.1 Page 31 |

▲back to top |

|

4.2 Page 32 |

▲back to top |

|

4.3 Page 33 |

▲back to top |

|

4.4 Page 34 |

▲back to top |

|

4.5 Page 35 |

▲back to top |

|

4.6 Page 36 |

▲back to top |

|

4.7 Page 37 |

▲back to top |

|

4.8 Page 38 |

▲back to top |

|

4.9 Page 39 |

▲back to top |

|

4.10 Page 40 |

▲back to top |

|

5 Pages 41-50 |

▲back to top |

|

5.1 Page 41 |

▲back to top |

|

5.2 Page 42 |

▲back to top |

|

5.3 Page 43 |

▲back to top |

|

5.4 Page 44 |

▲back to top |

|

5.5 Page 45 |

▲back to top |

|

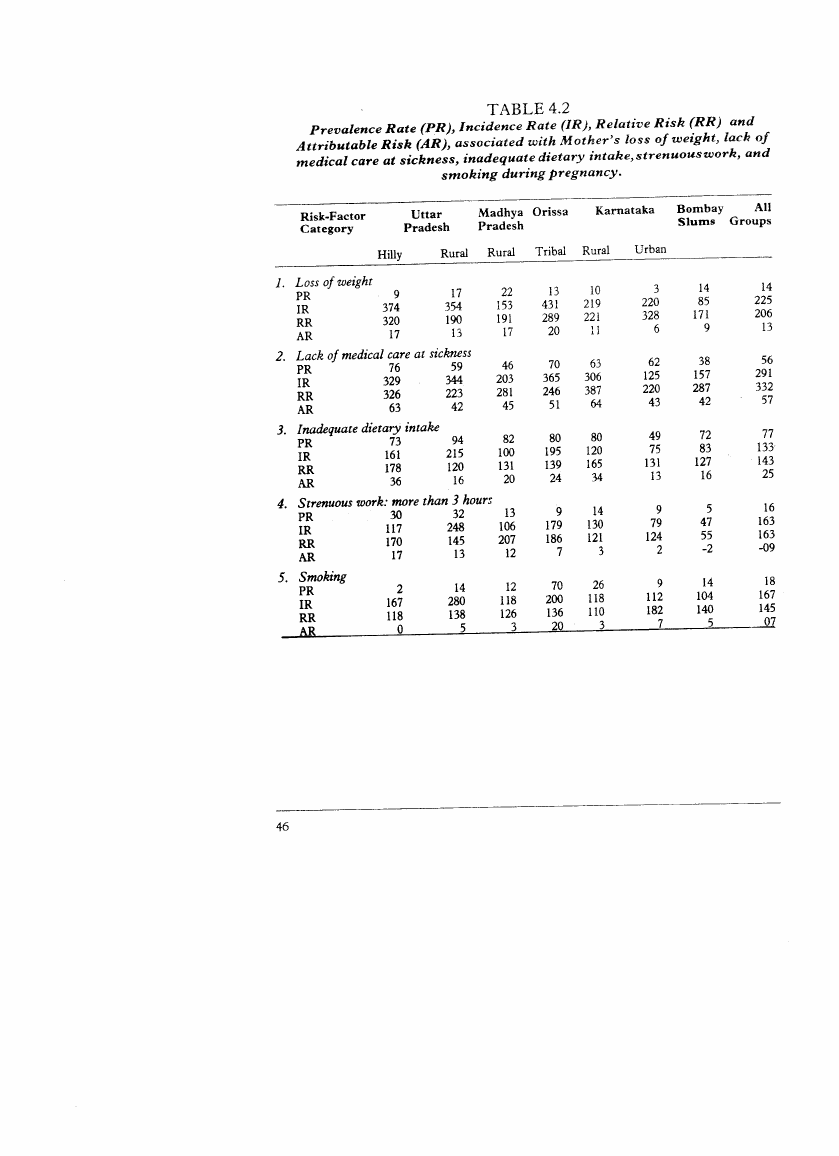

5.6 Page 46 |

▲back to top |

|

5.7 Page 47 |

▲back to top |

|

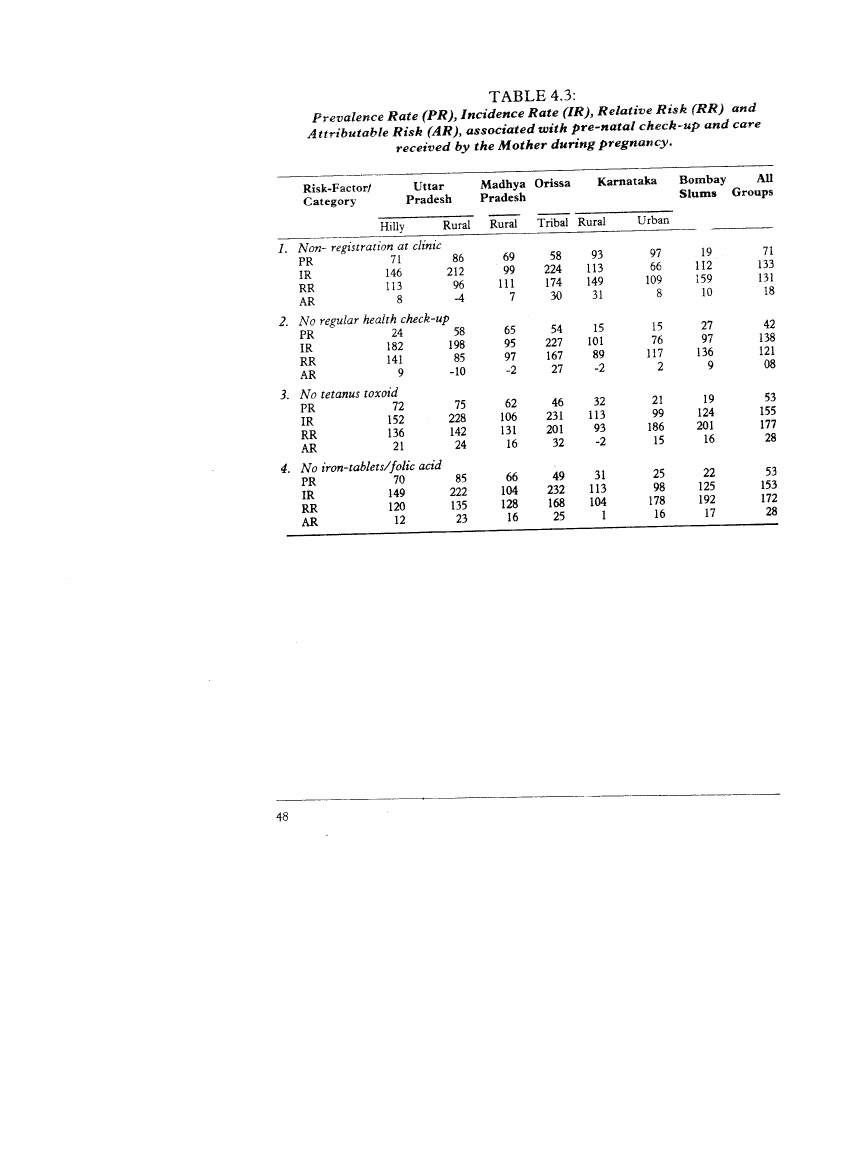

5.8 Page 48 |

▲back to top |

|

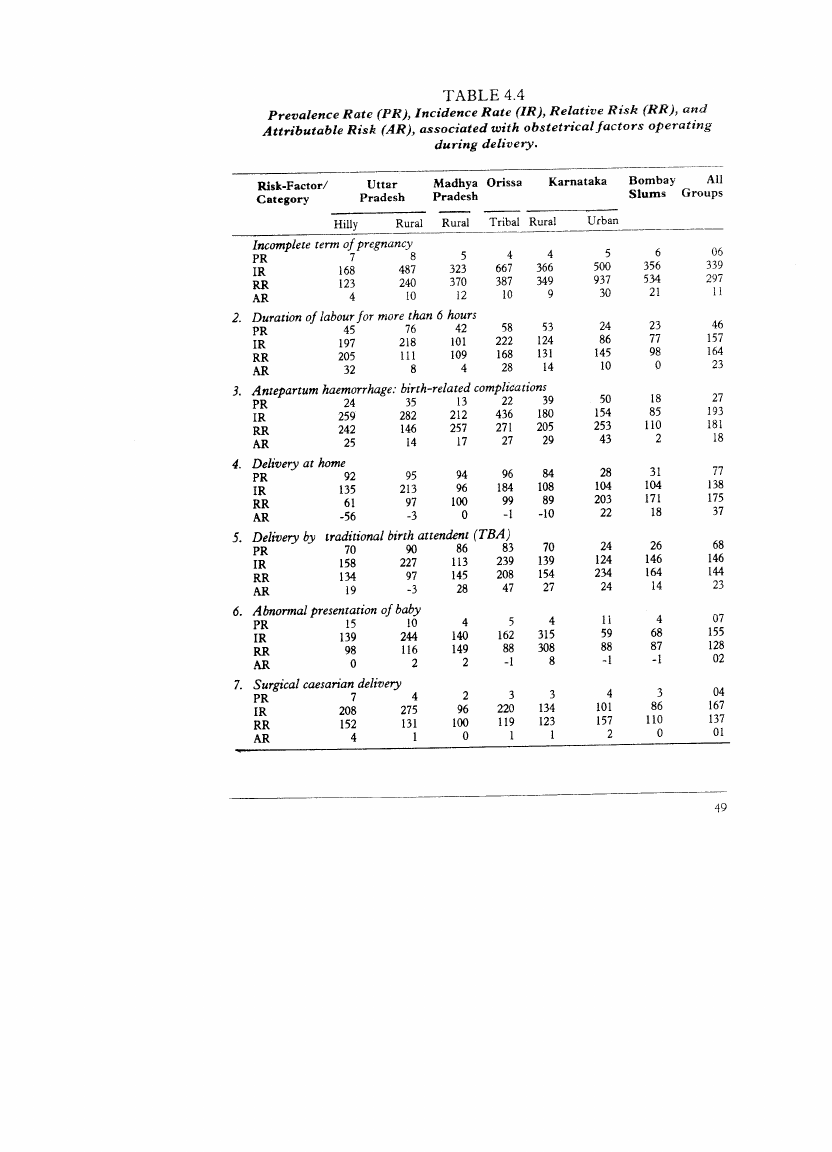

5.9 Page 49 |

▲back to top |

|

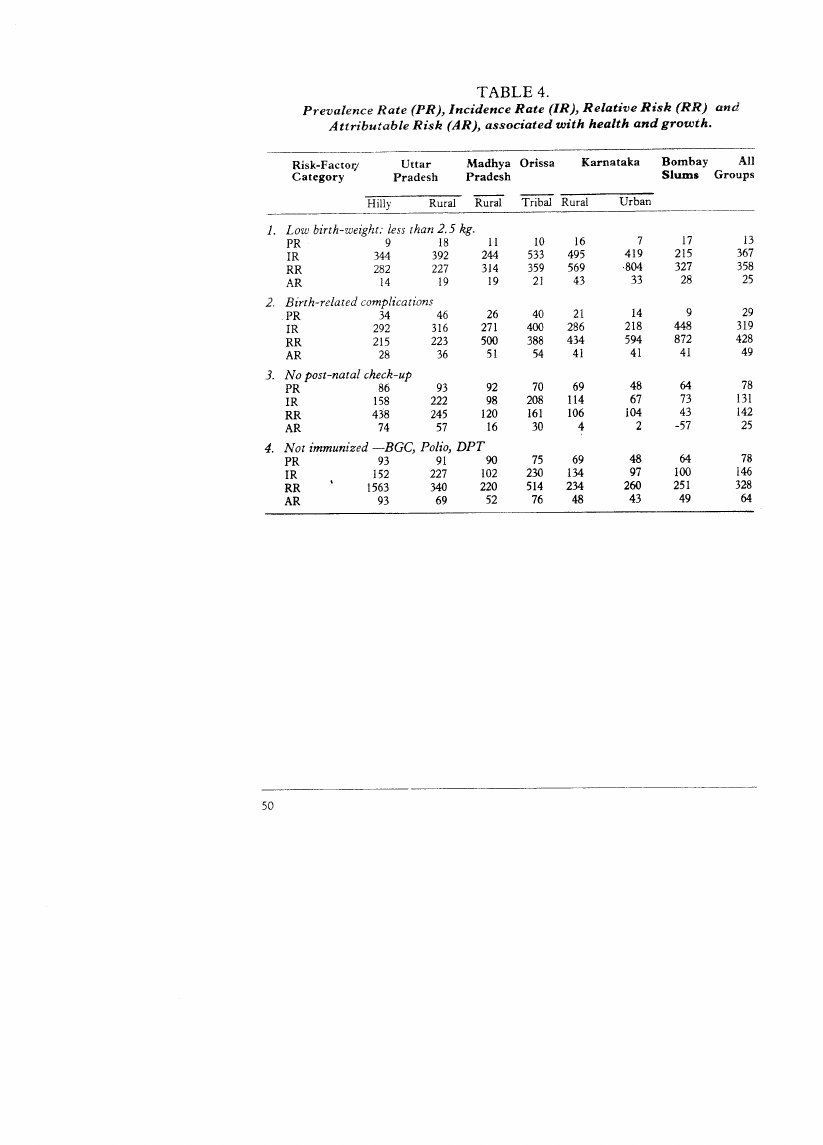

5.10 Page 50 |

▲back to top |

|

6 Pages 51-60 |

▲back to top |

|

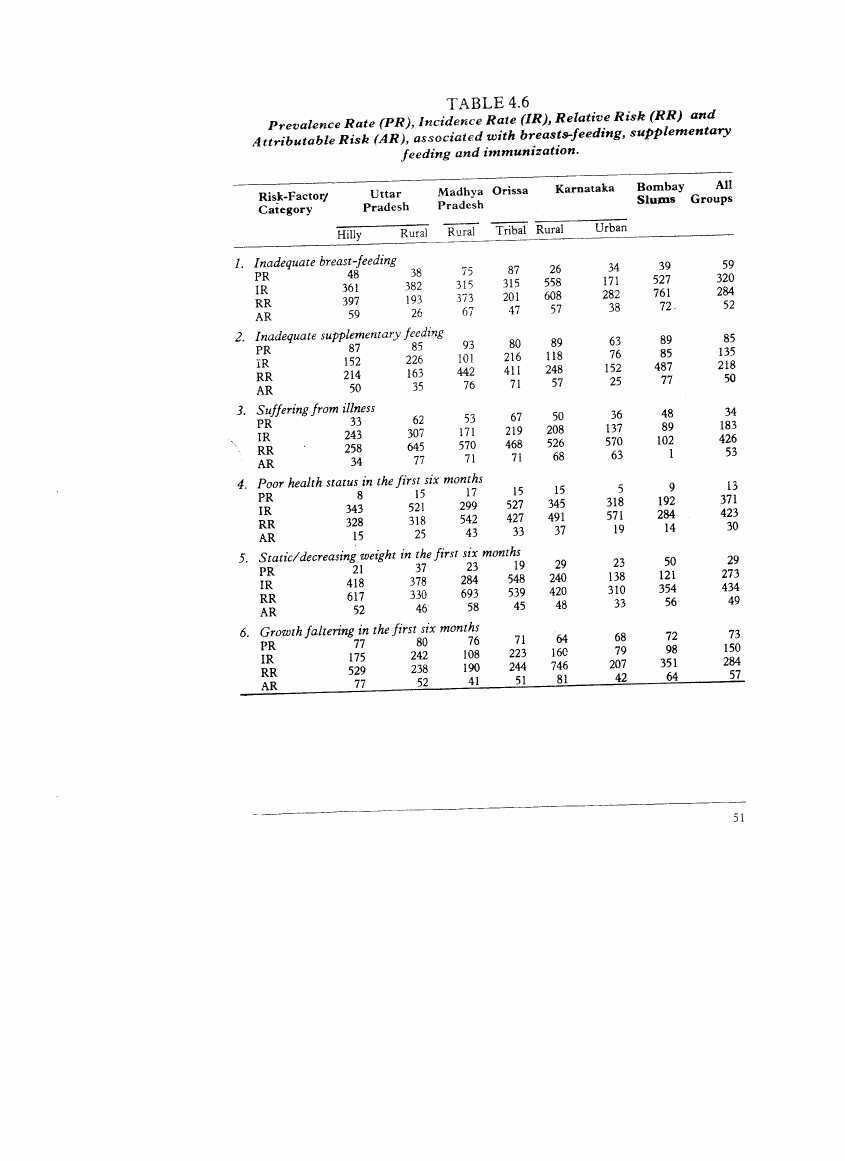

6.1 Page 51 |

▲back to top |

|

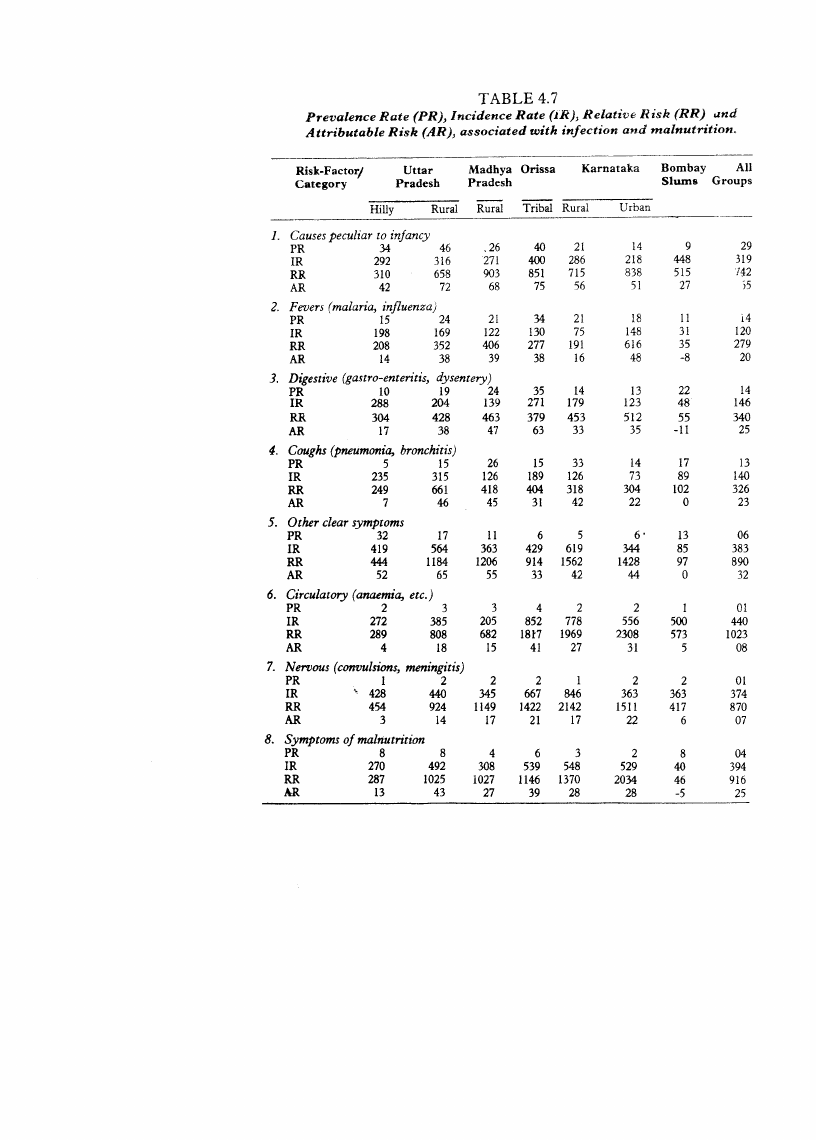

6.2 Page 52 |

▲back to top |

|

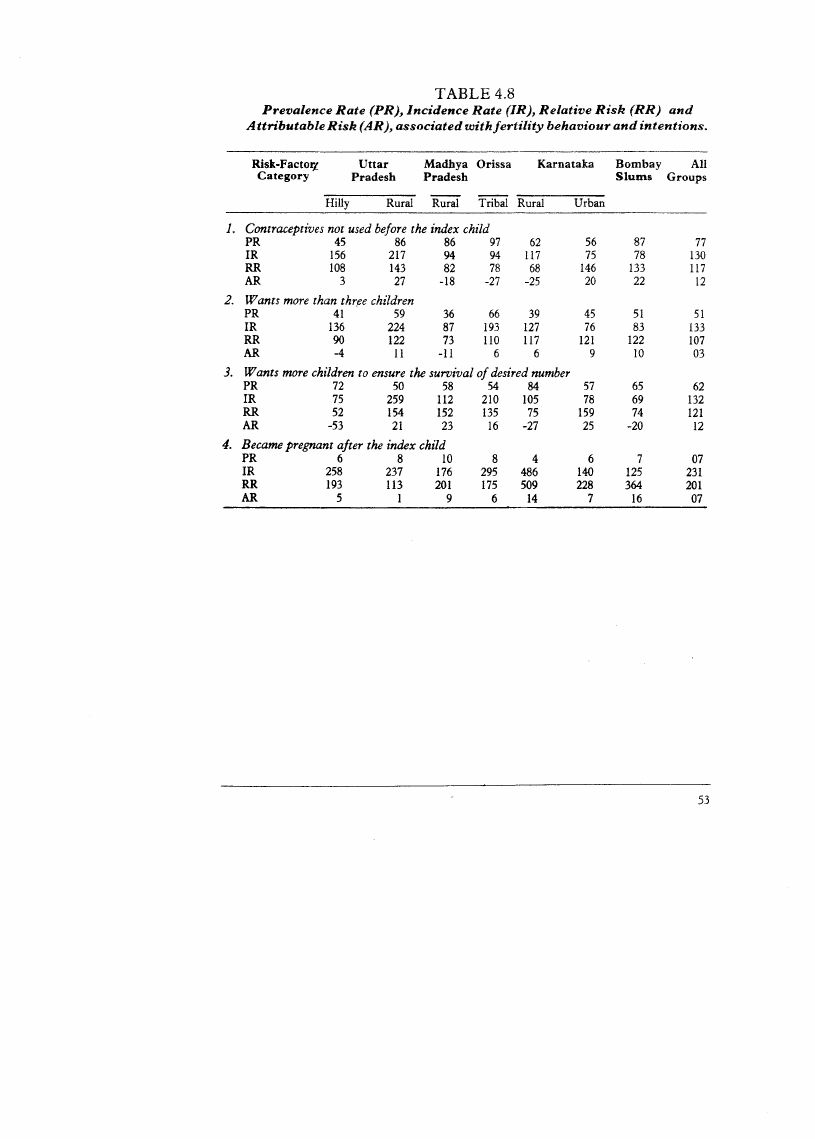

6.3 Page 53 |

▲back to top |

|

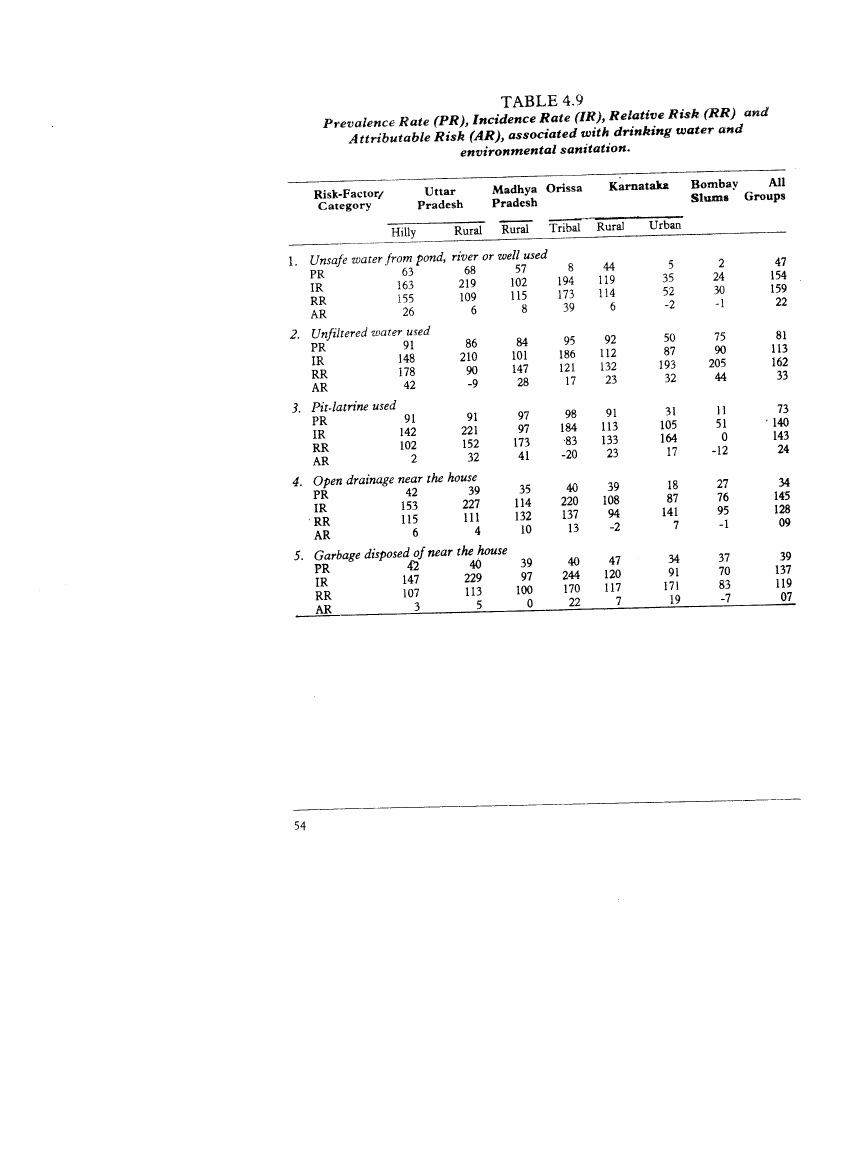

6.4 Page 54 |

▲back to top |

|

6.5 Page 55 |

▲back to top |

|

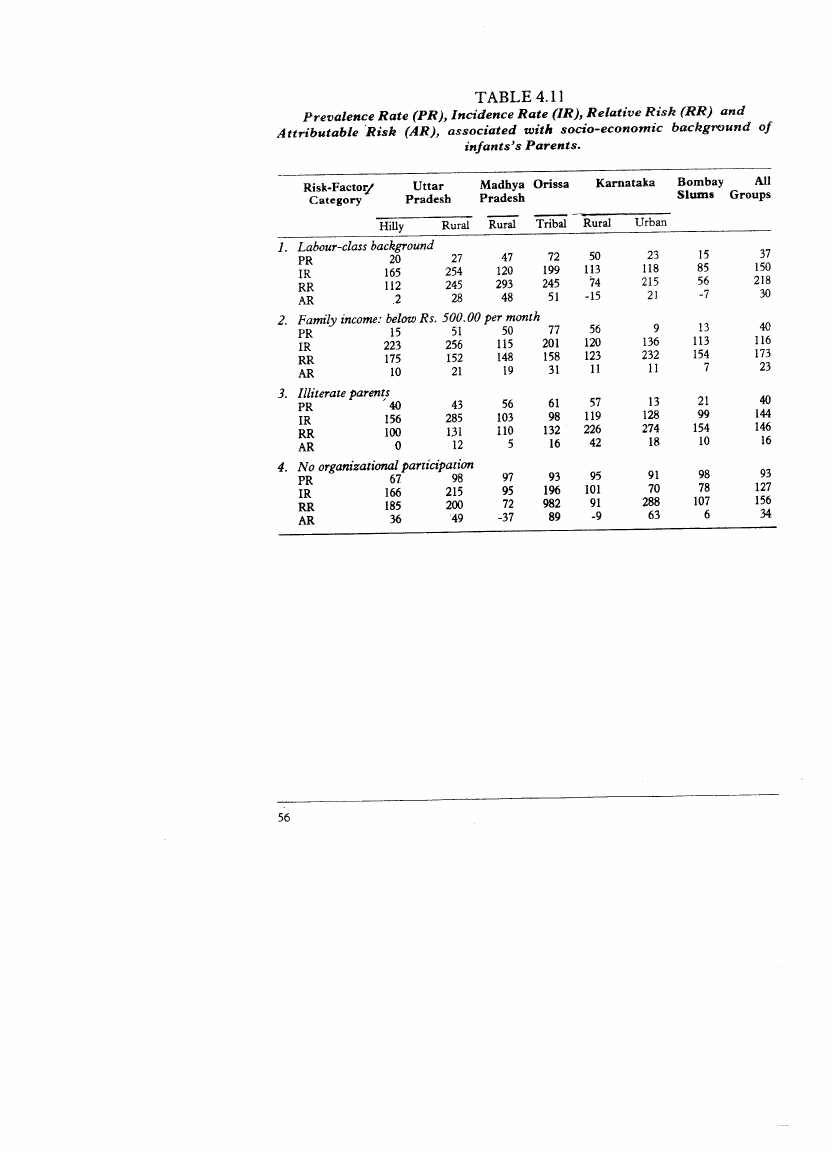

6.6 Page 56 |

▲back to top |

|

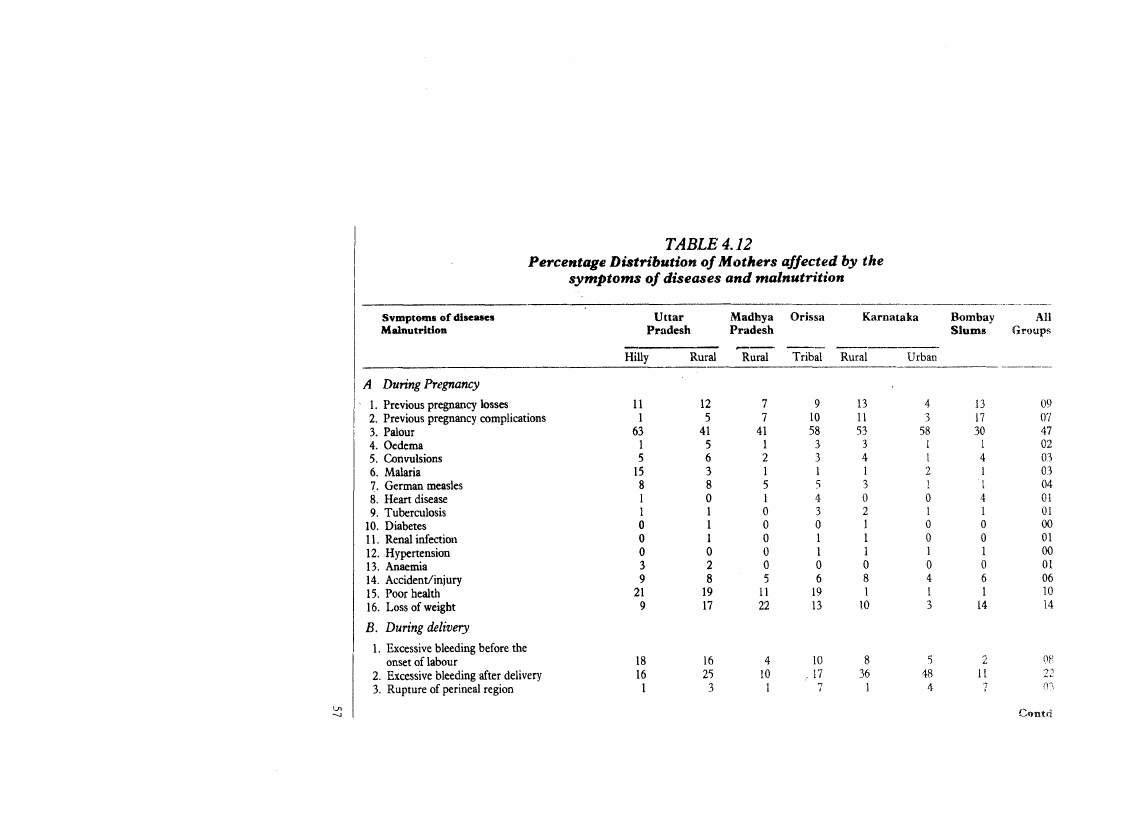

6.7 Page 57 |

▲back to top |

|

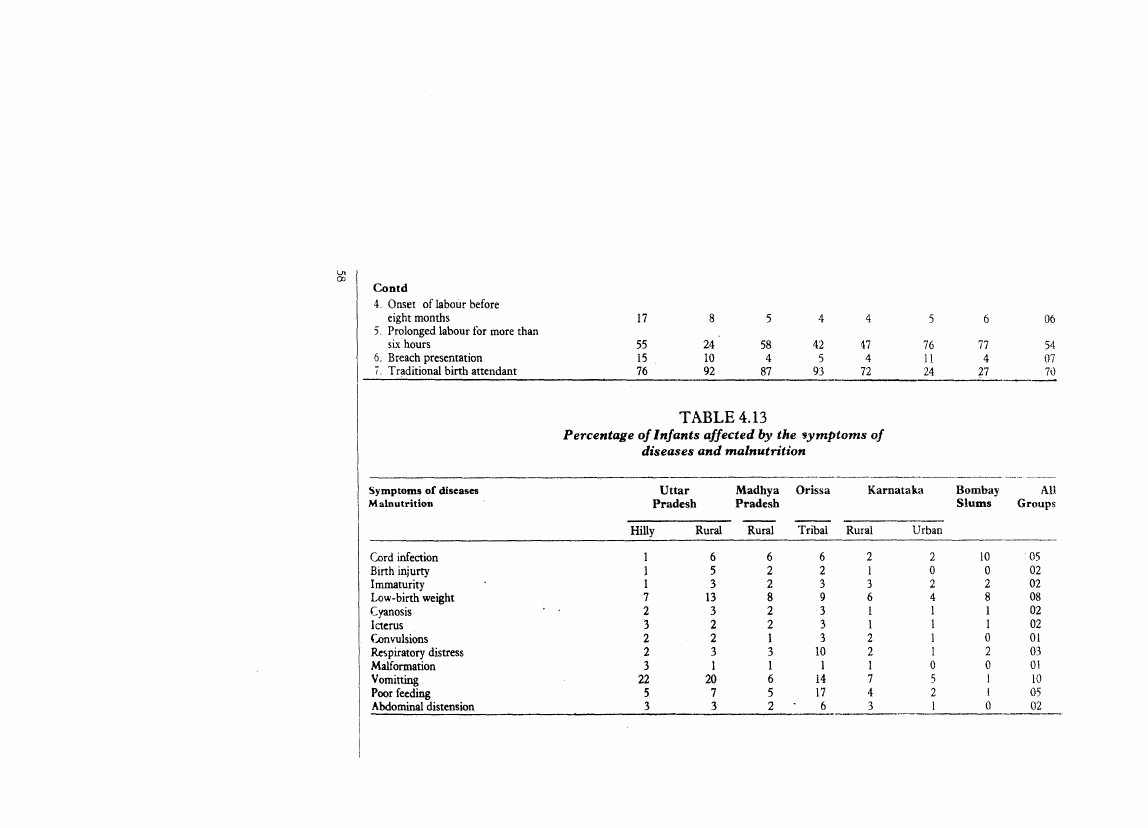

6.8 Page 58 |

▲back to top |

|

6.9 Page 59 |

▲back to top |

|

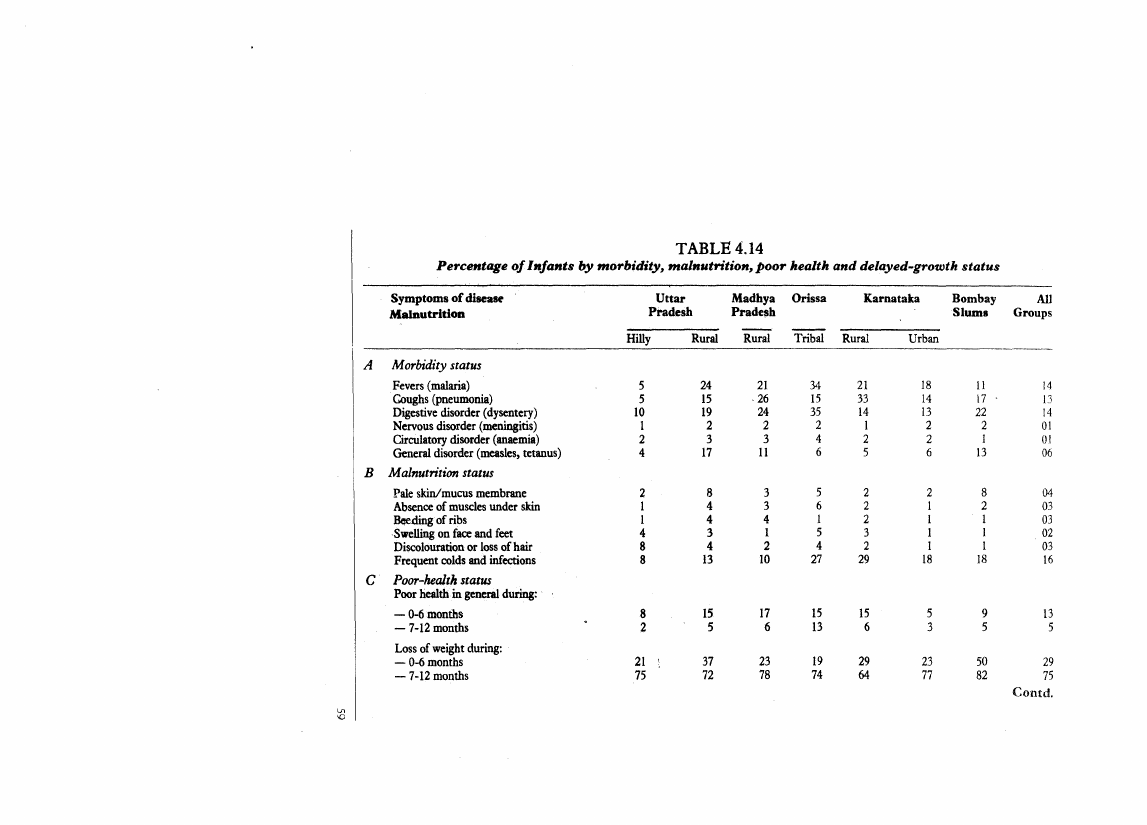

6.10 Page 60 |

▲back to top |

|

7 Pages 61-70 |

▲back to top |

|

7.1 Page 61 |

▲back to top |

|

7.2 Page 62 |

▲back to top |

|

7.3 Page 63 |

▲back to top |

|

7.4 Page 64 |

▲back to top |

|

7.5 Page 65 |

▲back to top |

|

7.6 Page 66 |

▲back to top |

|

7.7 Page 67 |

▲back to top |

|

7.8 Page 68 |

▲back to top |

|

7.9 Page 69 |

▲back to top |

|

7.10 Page 70 |

▲back to top |

|

8 Pages 71-80 |

▲back to top |

|

8.1 Page 71 |

▲back to top |

|

8.2 Page 72 |

▲back to top |

|

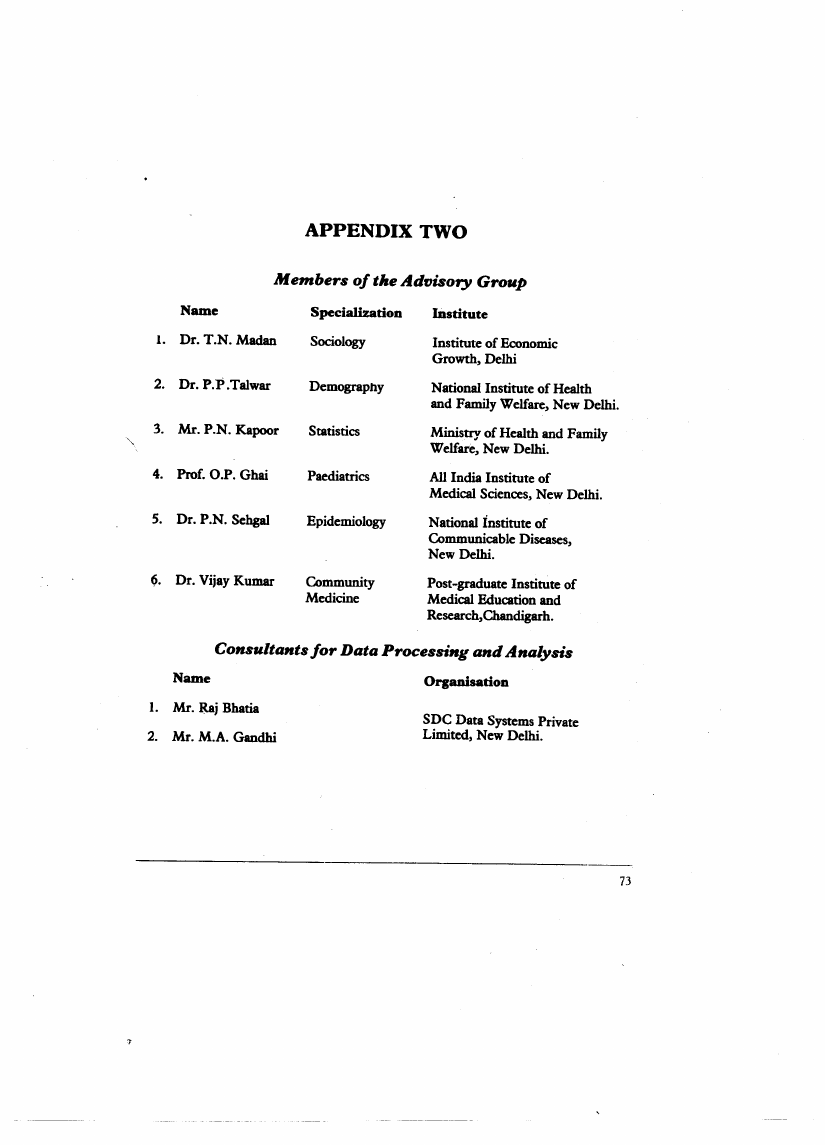

8.3 Page 73 |

▲back to top |

|

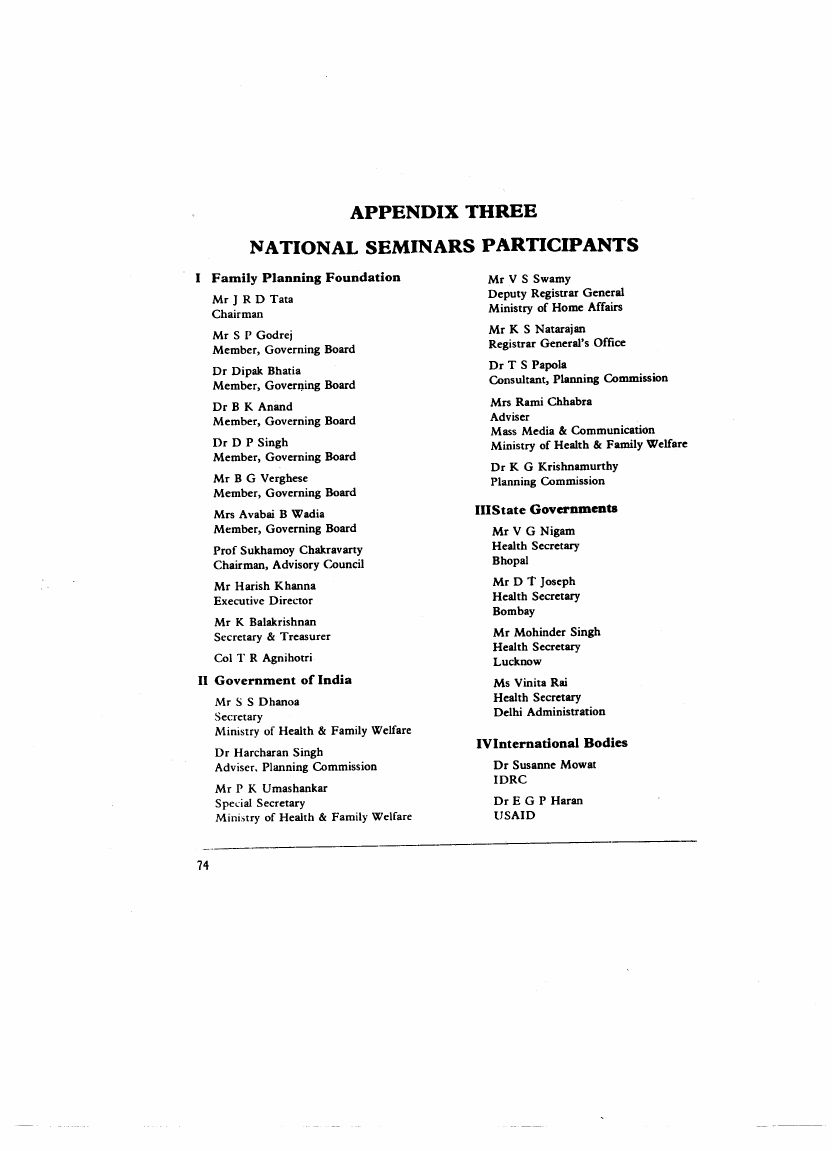

8.4 Page 74 |

▲back to top |

|

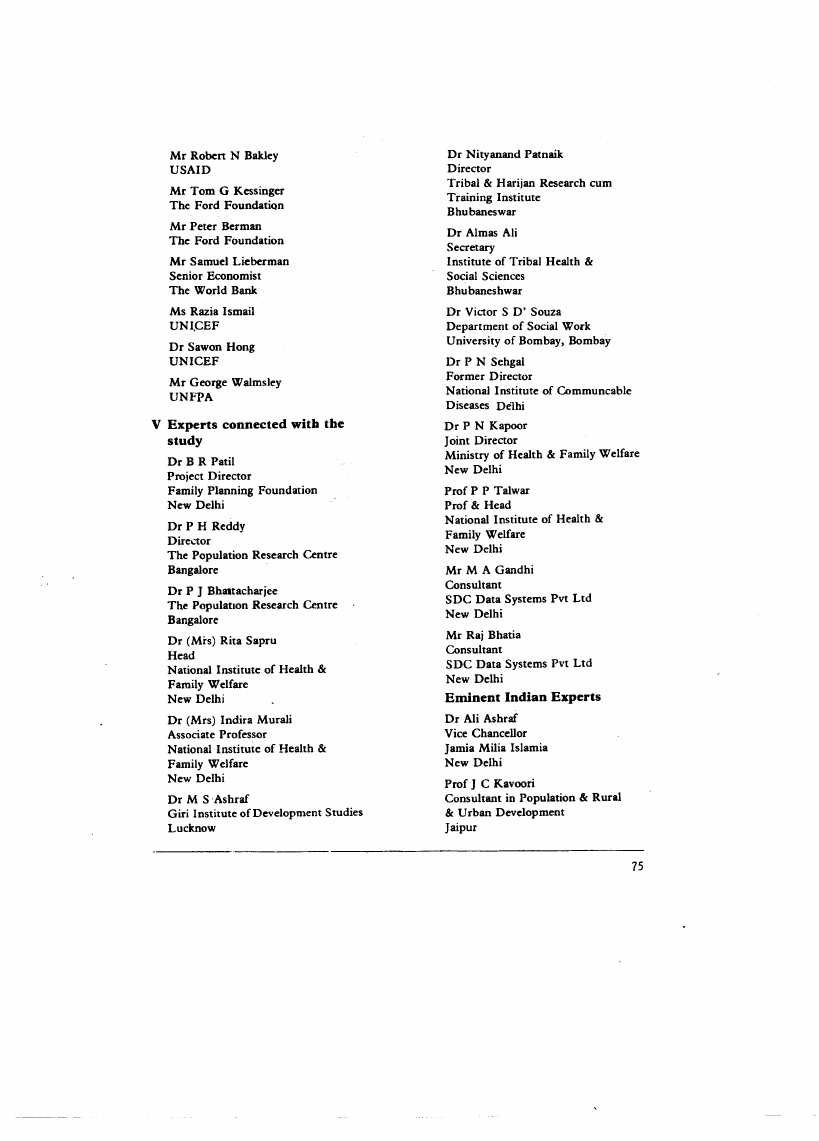

8.5 Page 75 |

▲back to top |

|

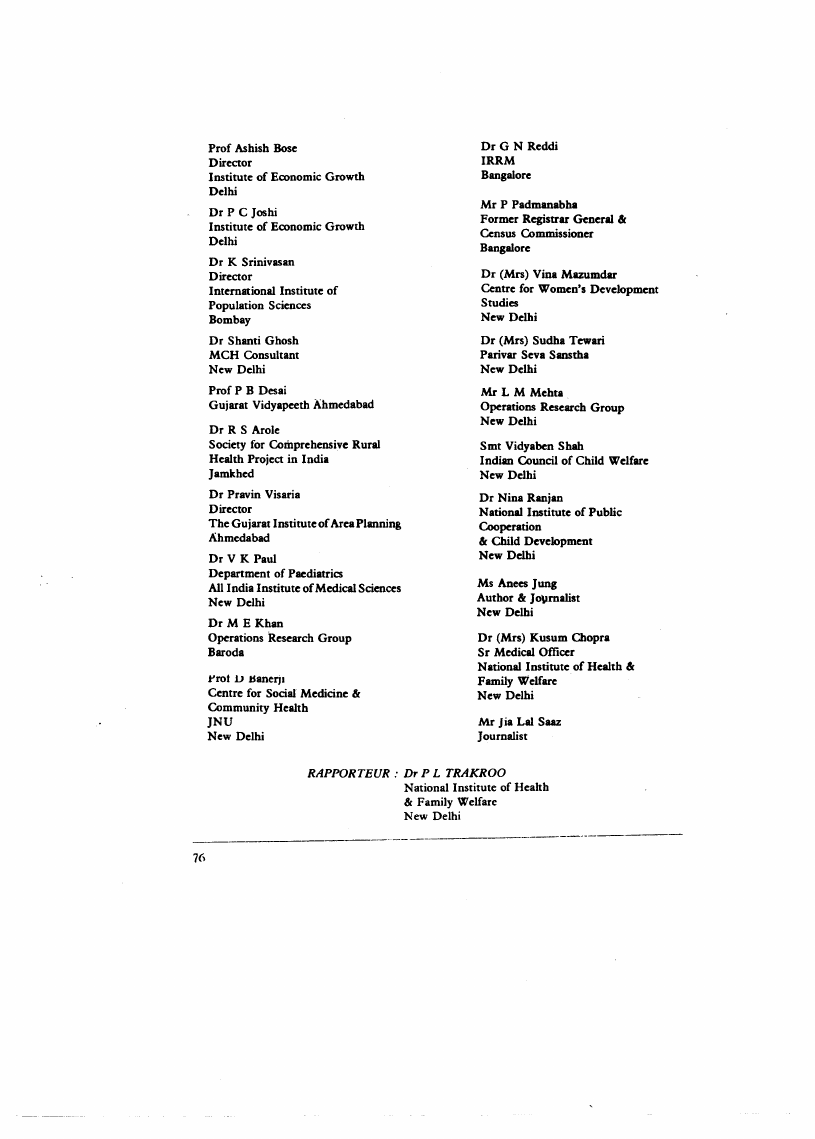

8.6 Page 76 |

▲back to top |

|

8.7 Page 77 |

▲back to top |

|

8.8 Page 78 |

▲back to top |

|

8.9 Page 79 |

▲back to top |

|

8.10 Page 80 |

▲back to top |

|

9 Pages 81-90 |

▲back to top |

|

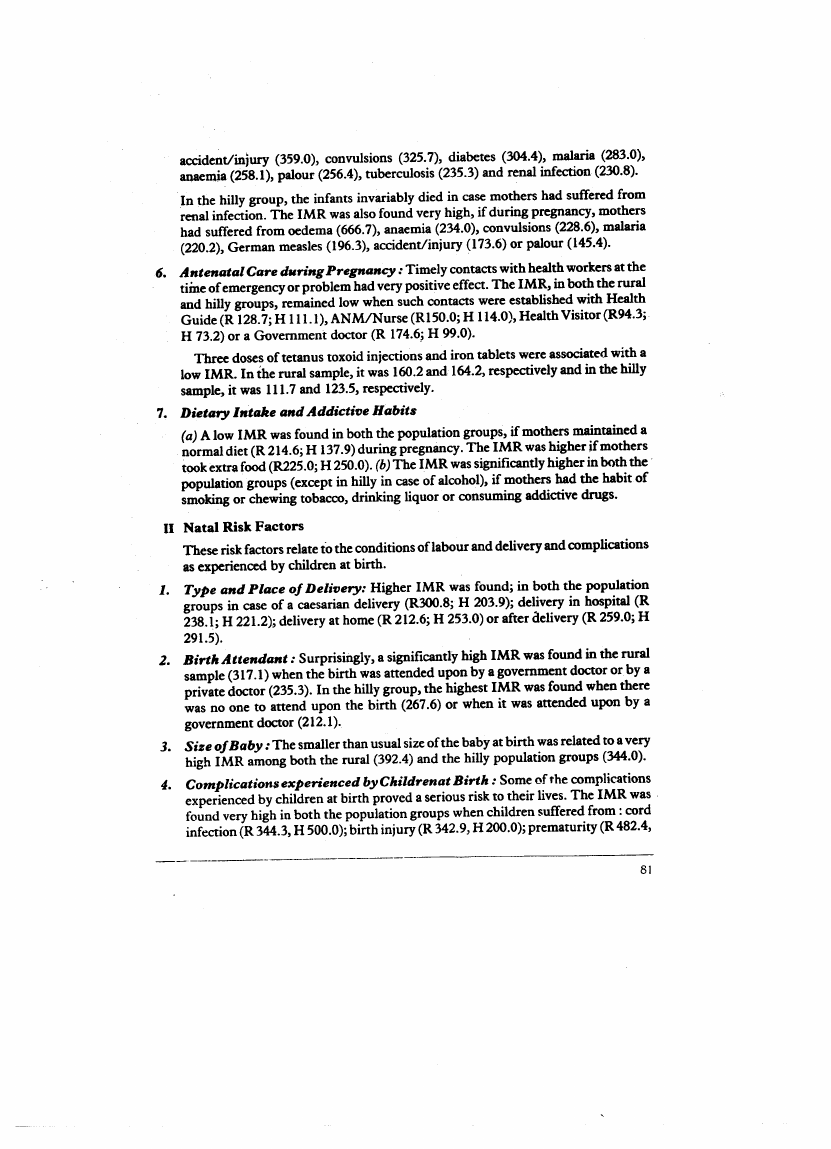

9.1 Page 81 |

▲back to top |

|

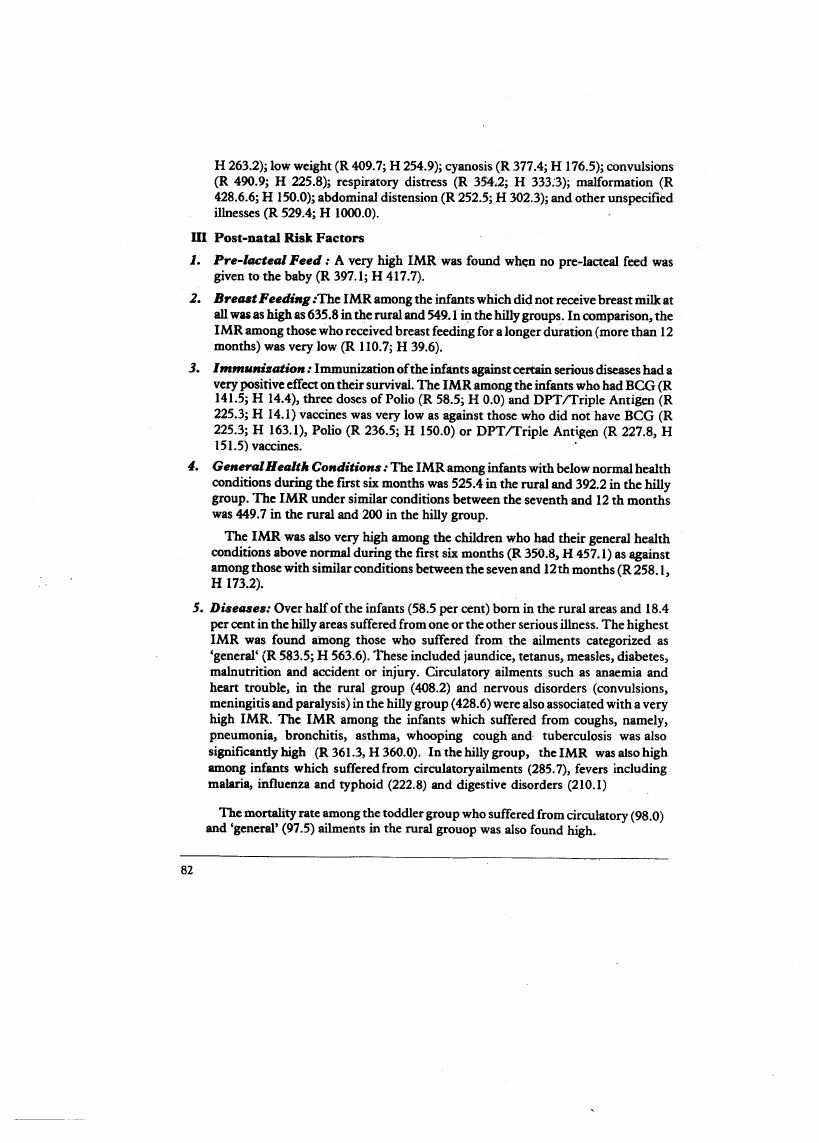

9.2 Page 82 |

▲back to top |

|

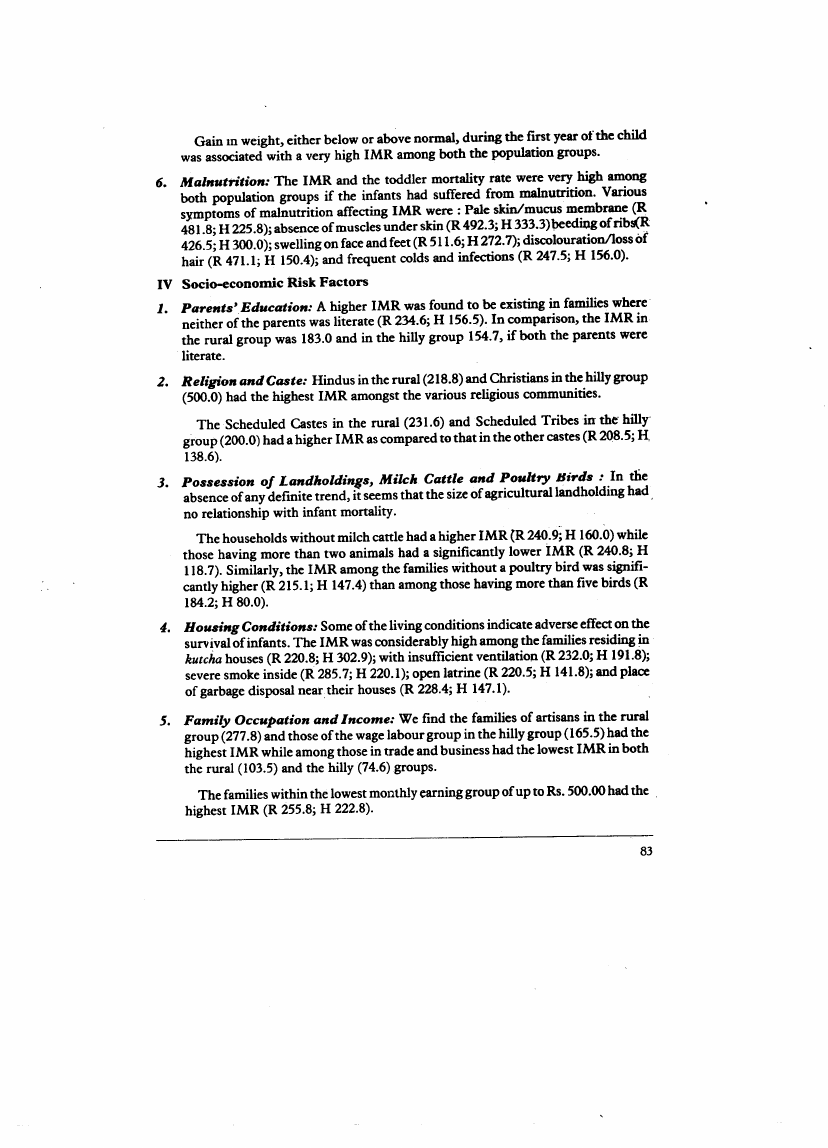

9.3 Page 83 |

▲back to top |

|

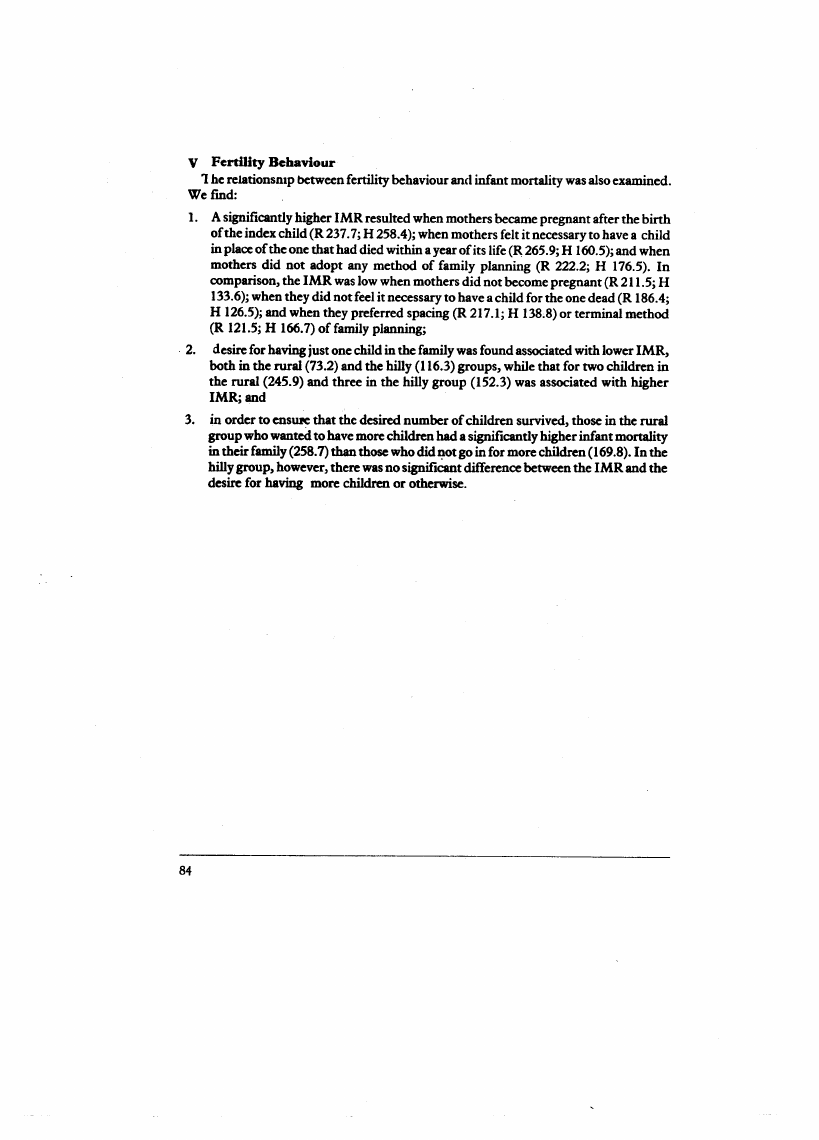

9.4 Page 84 |

▲back to top |

|

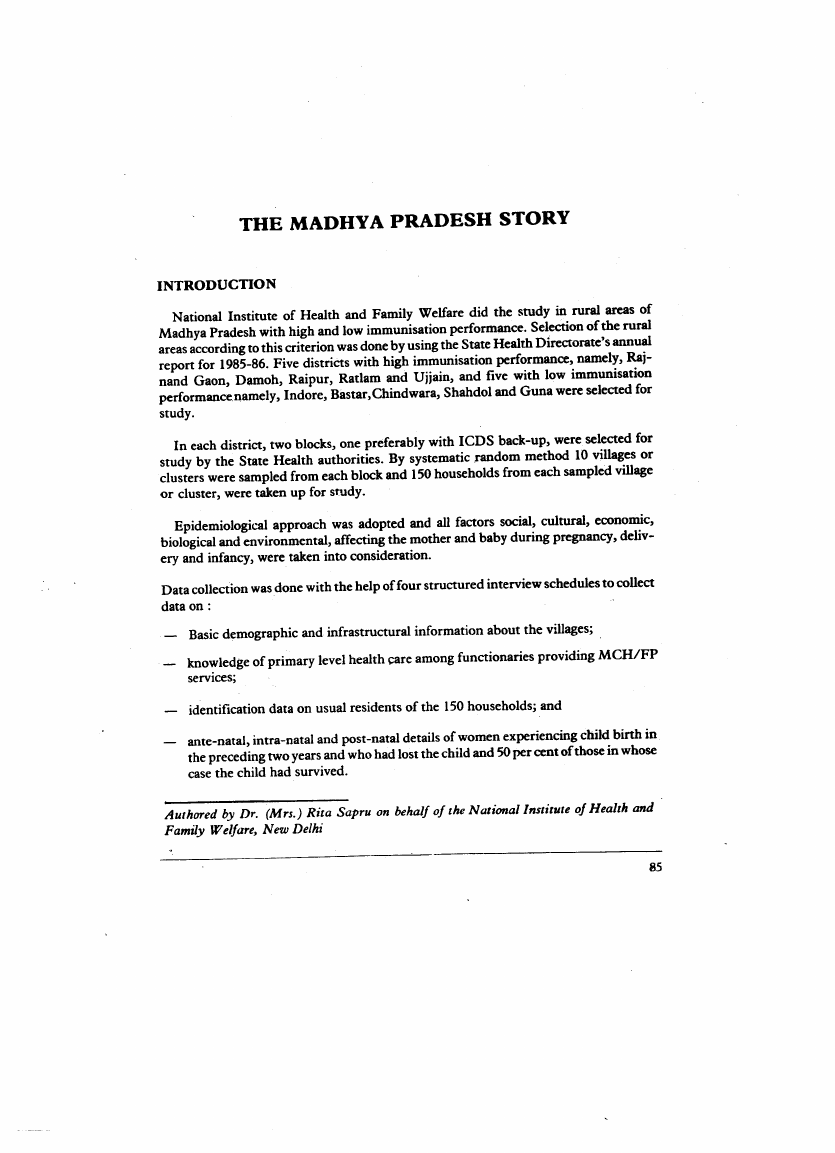

9.5 Page 85 |

▲back to top |

|

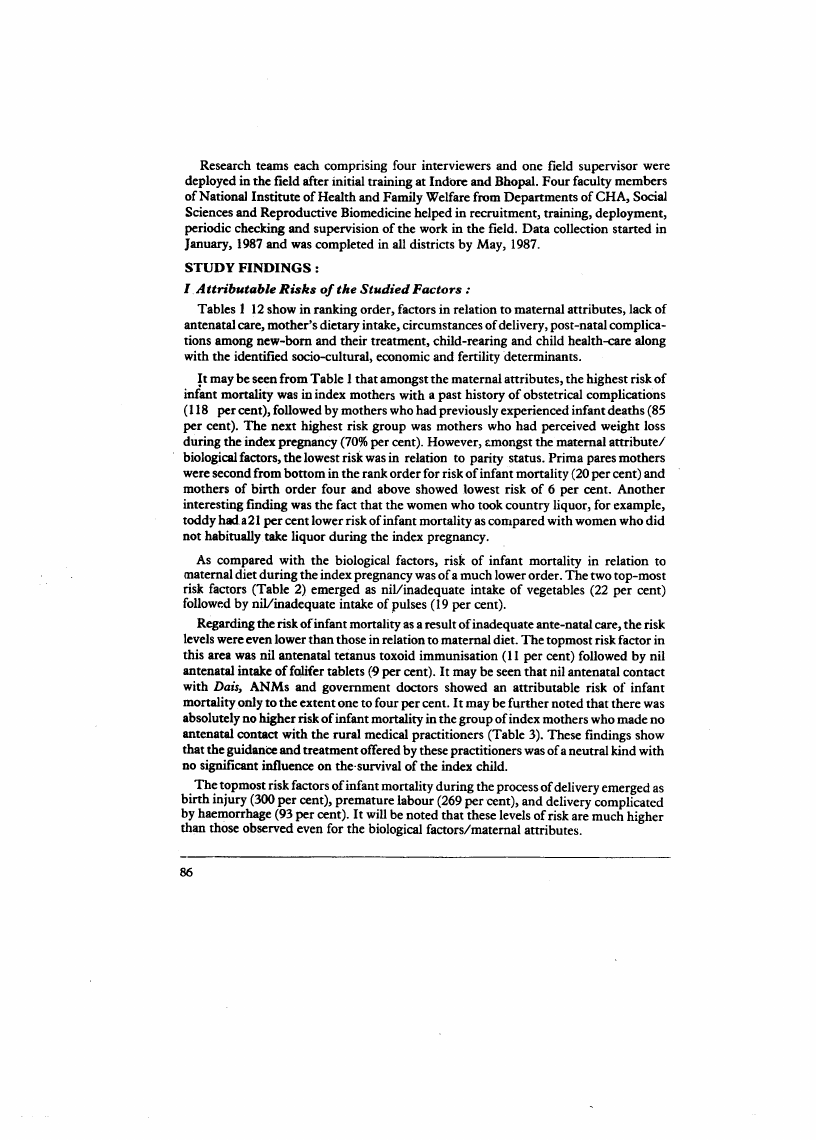

9.6 Page 86 |

▲back to top |

|

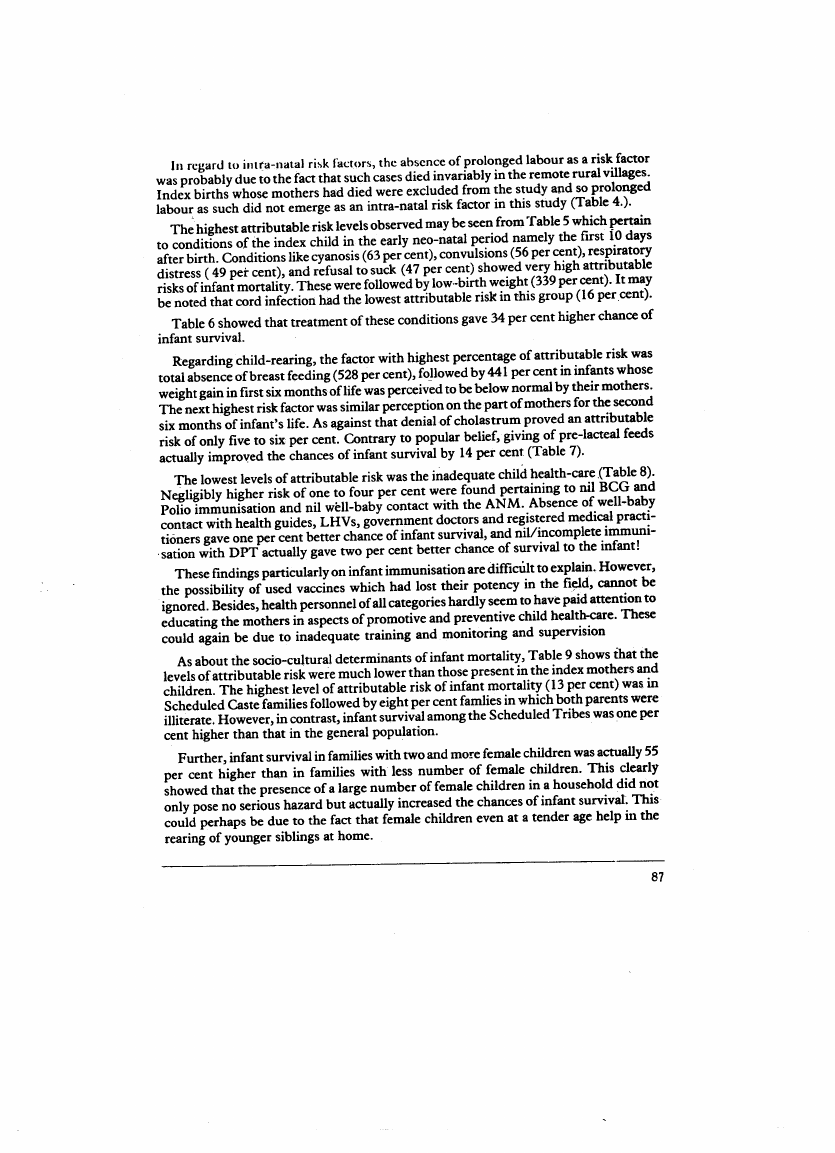

9.7 Page 87 |

▲back to top |

|

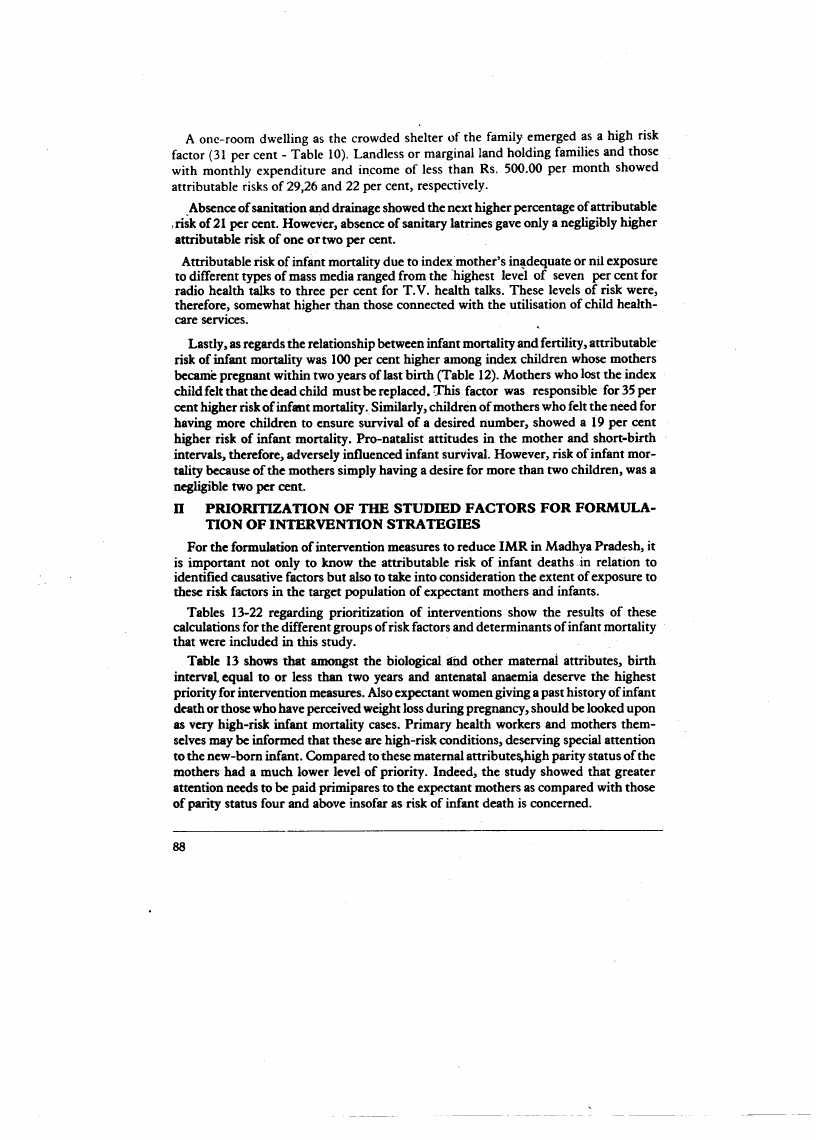

9.8 Page 88 |

▲back to top |

|

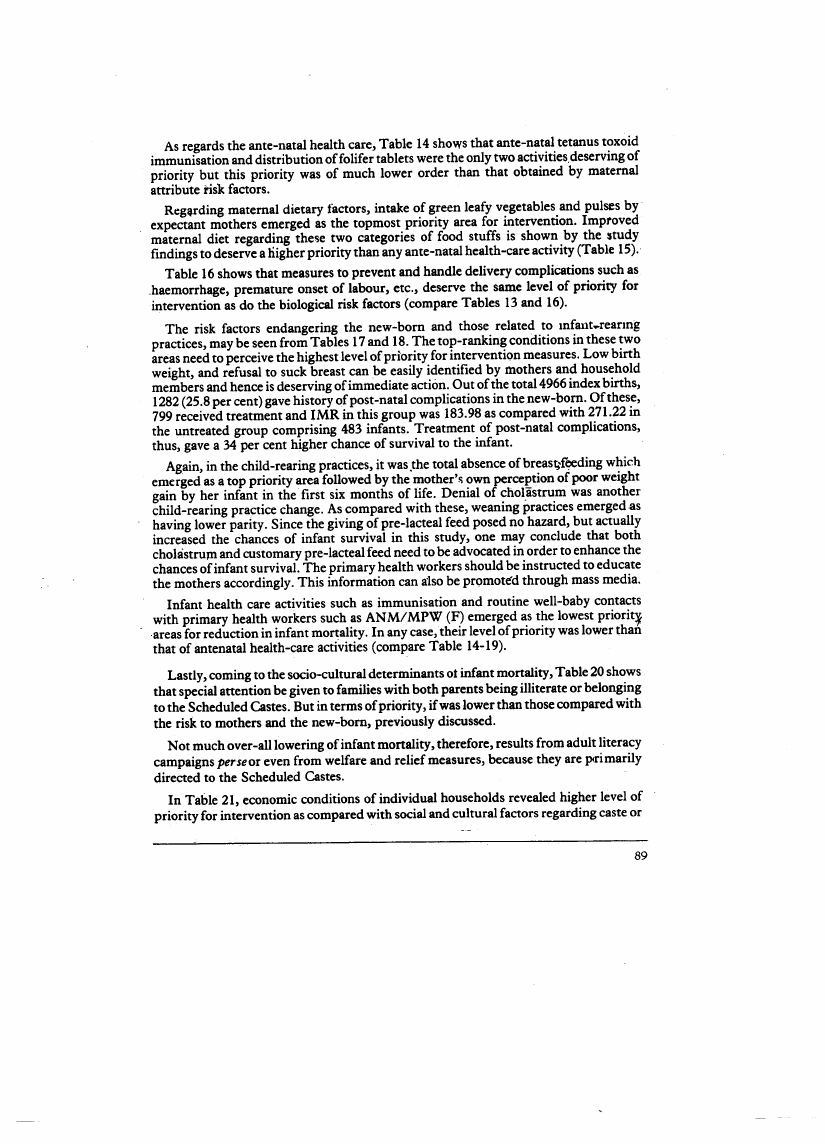

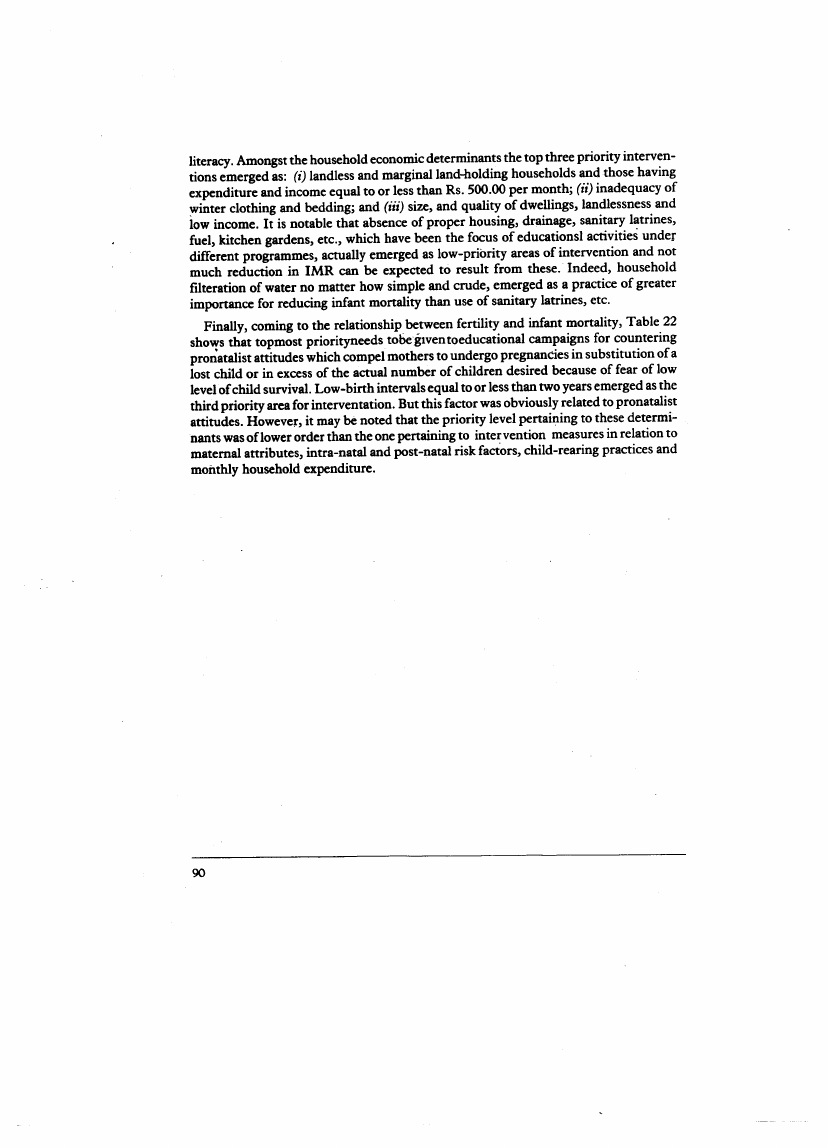

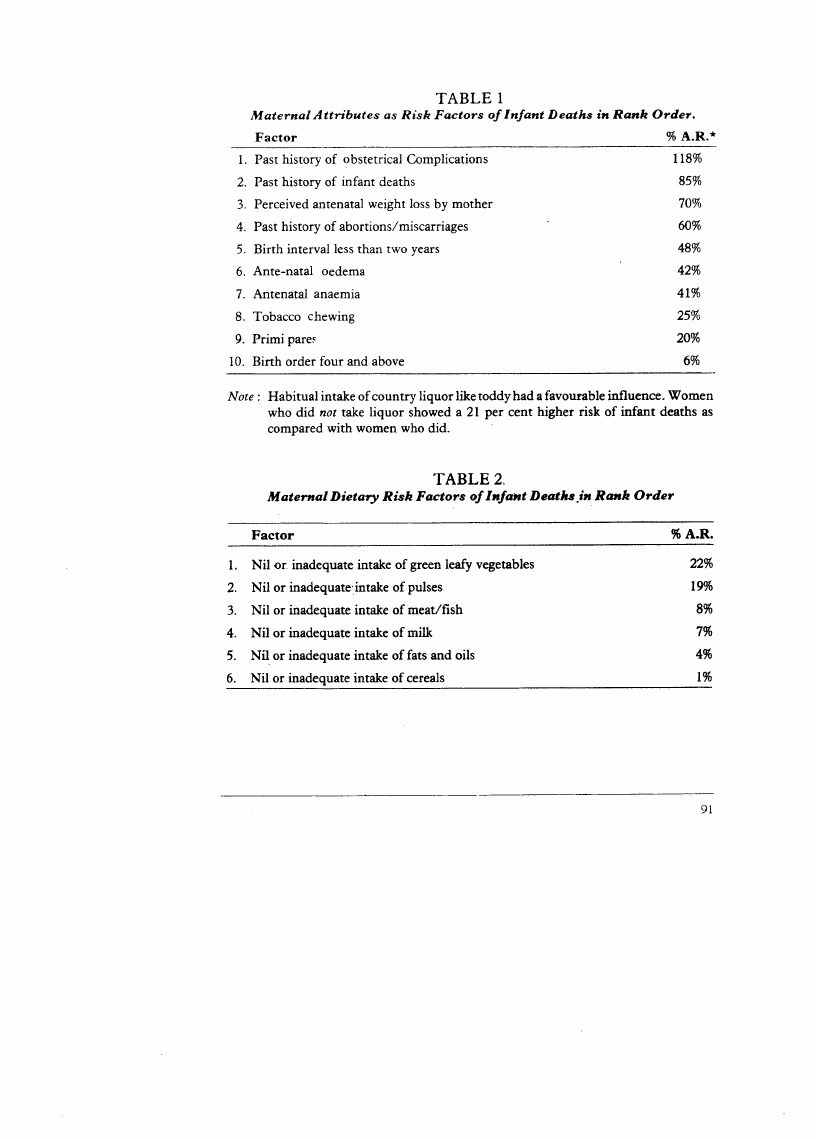

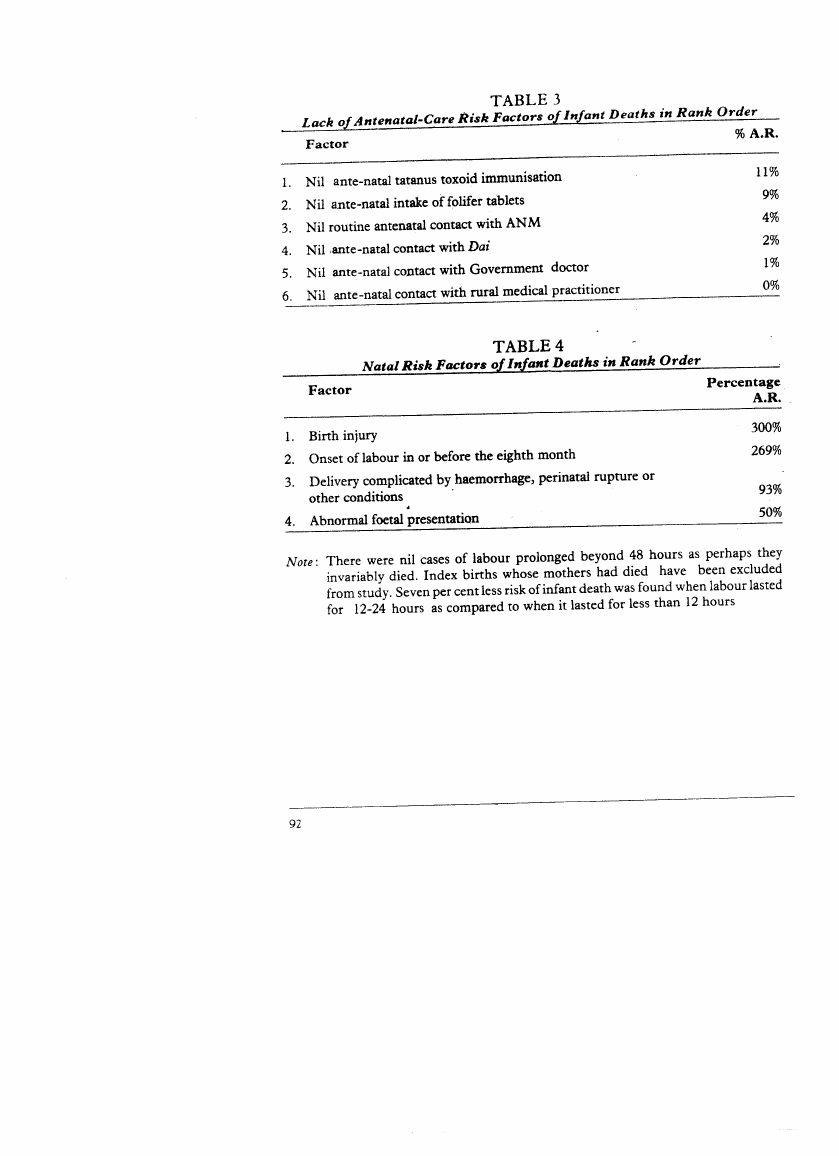

9.9 Page 89 |

▲back to top |

|

9.10 Page 90 |

▲back to top |

|

10 Pages 91-100 |

▲back to top |

|

10.1 Page 91 |

▲back to top |

|

10.2 Page 92 |

▲back to top |

|

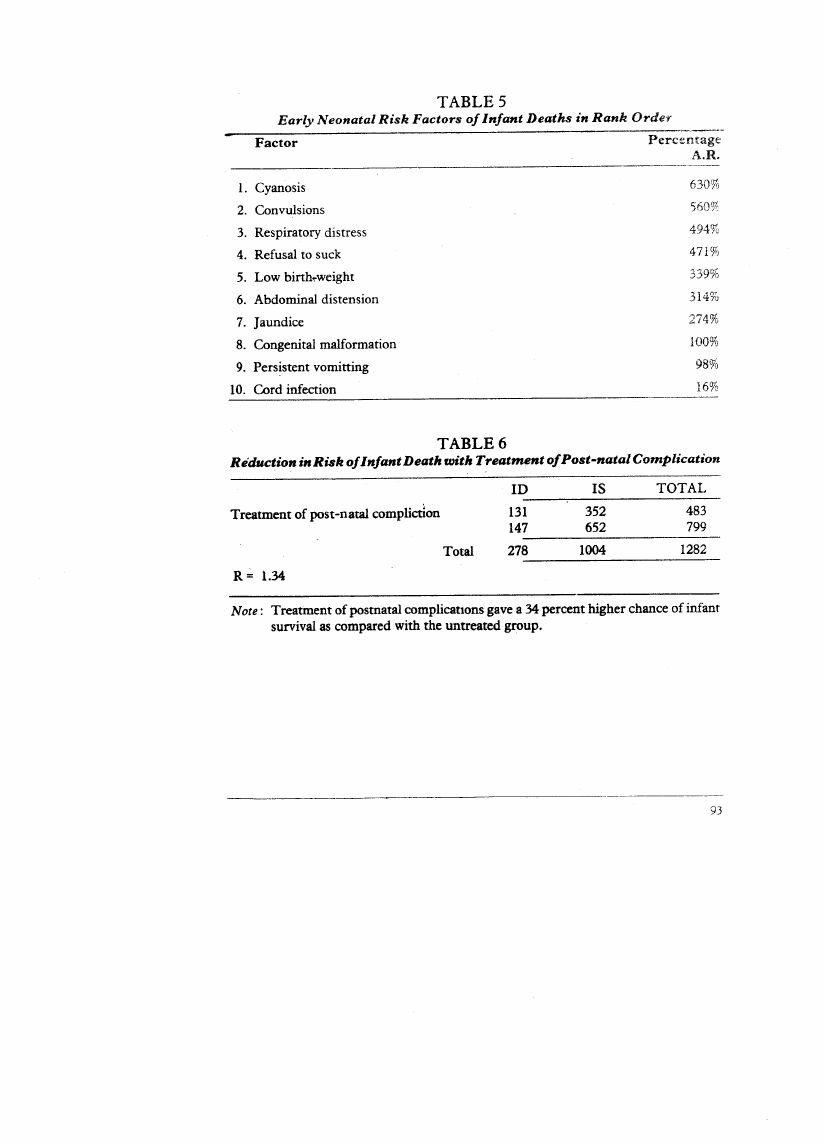

10.3 Page 93 |

▲back to top |

|

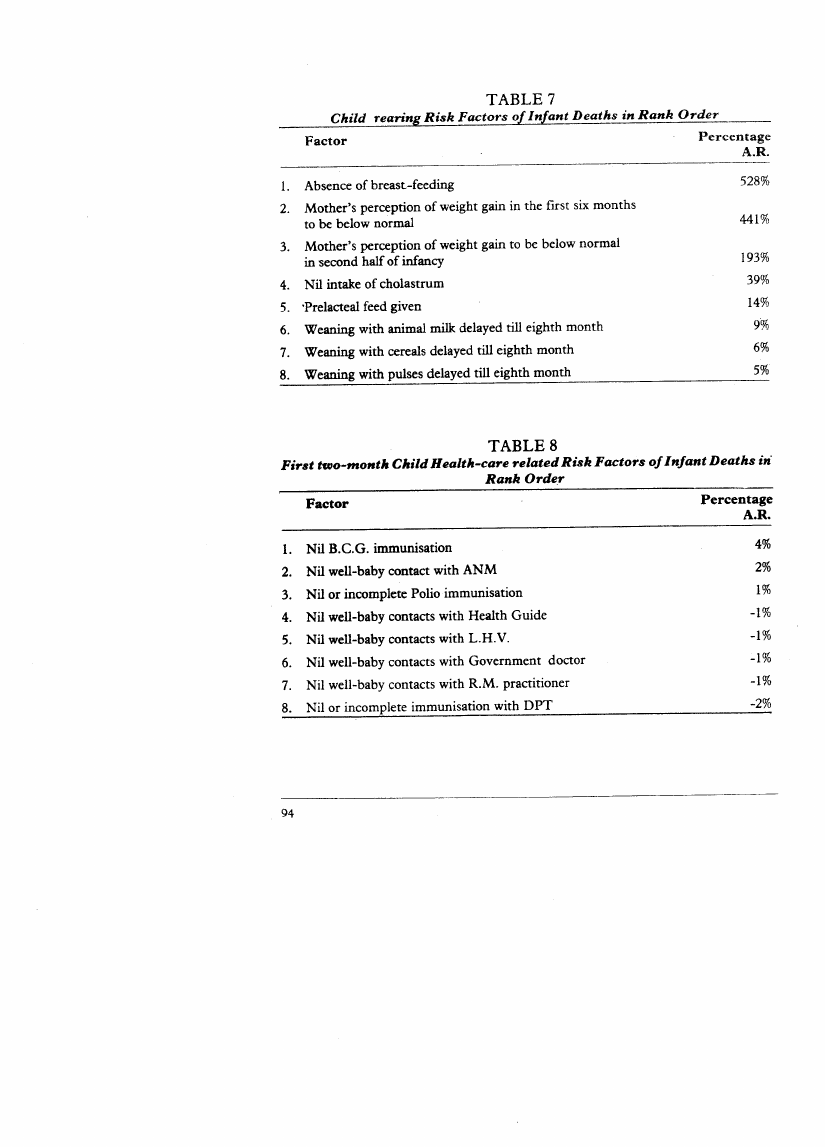

10.4 Page 94 |

▲back to top |

|

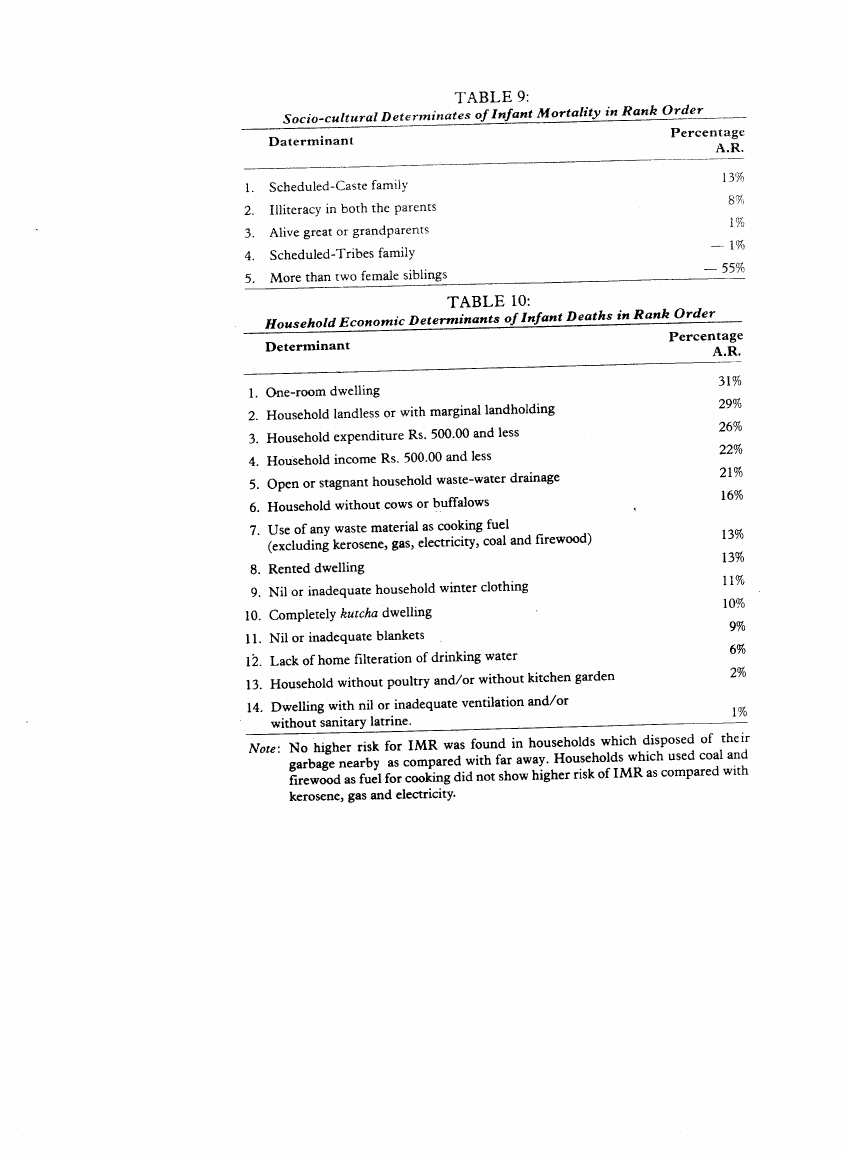

10.5 Page 95 |

▲back to top |

|

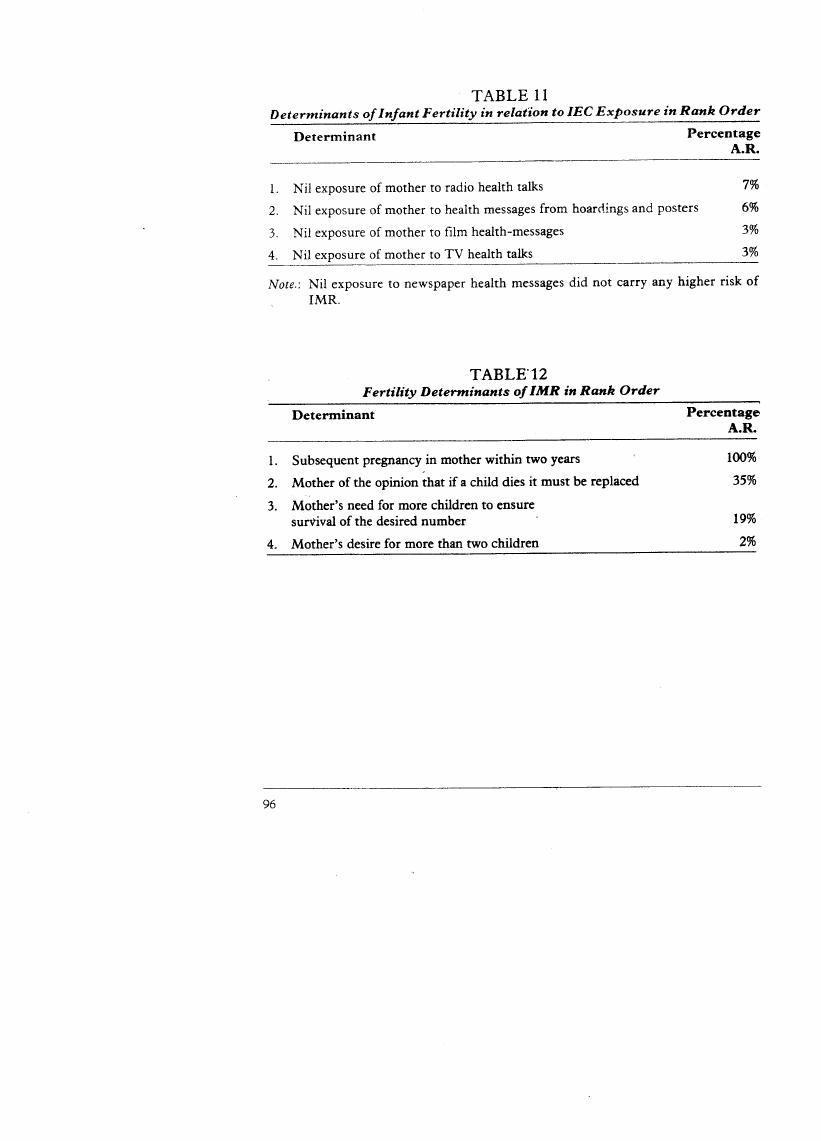

10.6 Page 96 |

▲back to top |

|

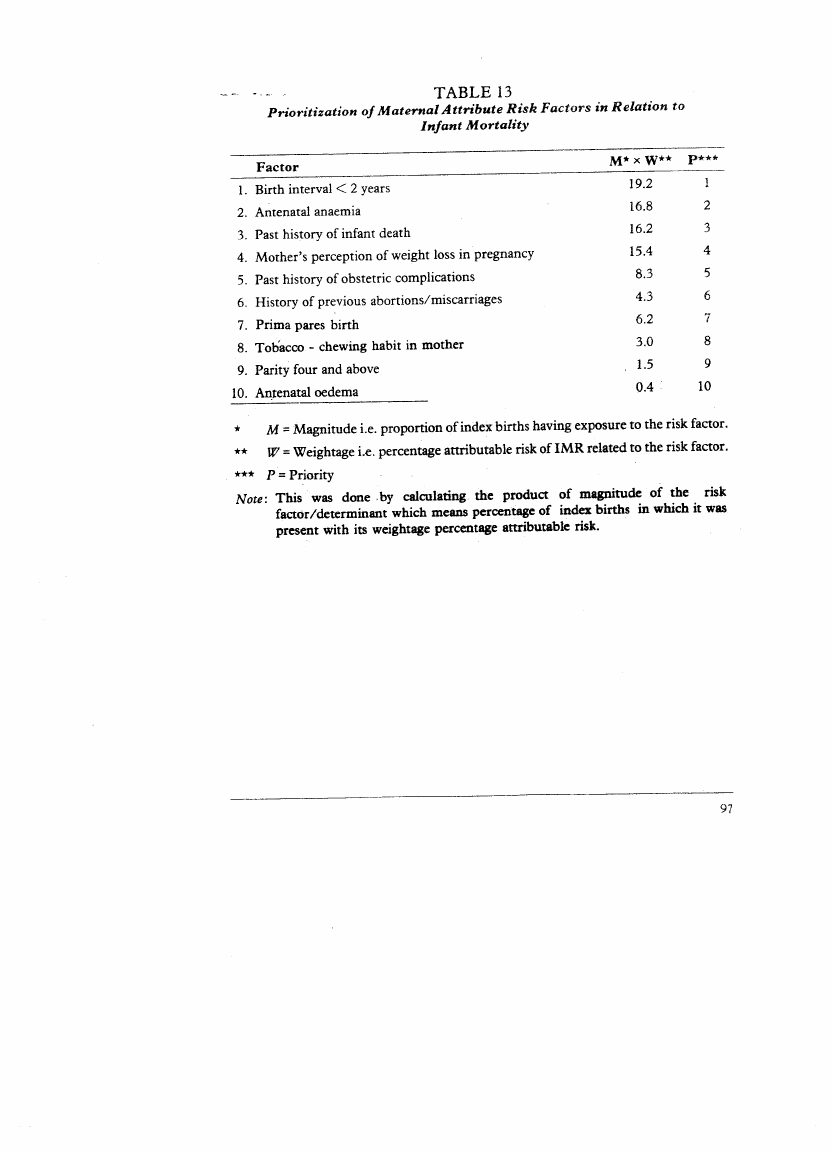

10.7 Page 97 |

▲back to top |

|

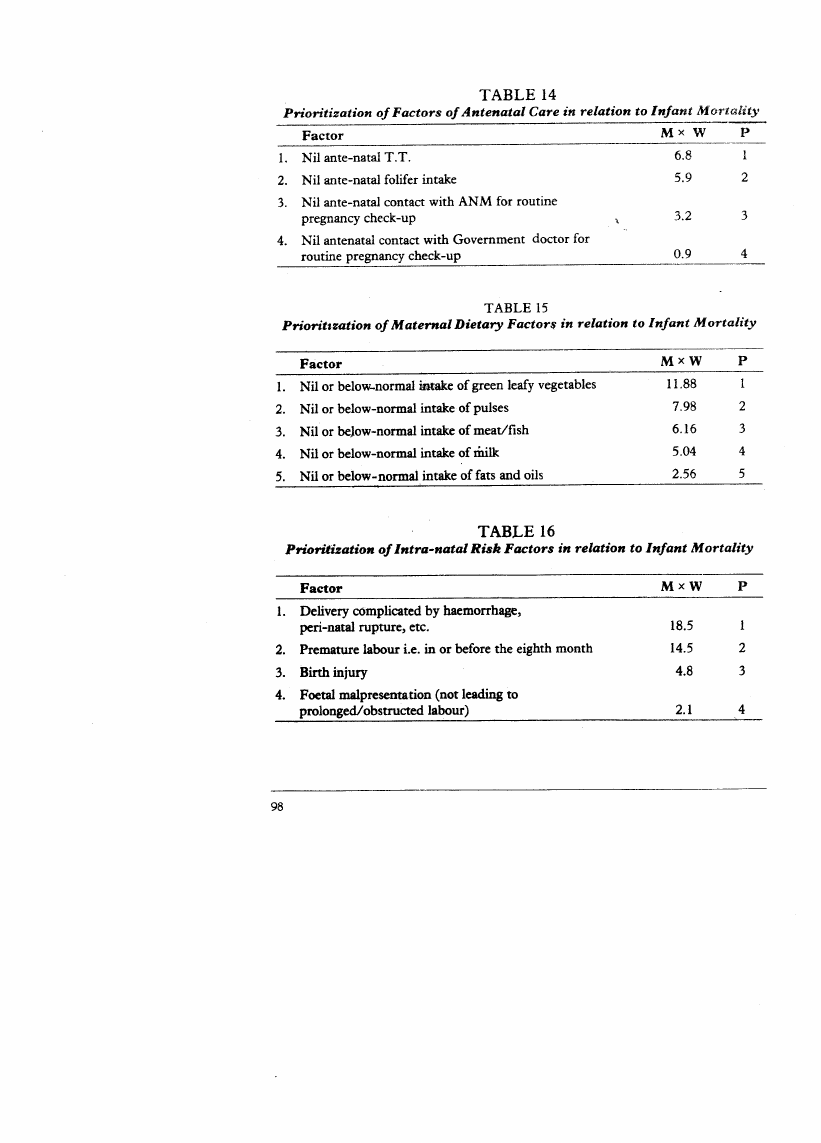

10.8 Page 98 |

▲back to top |

|

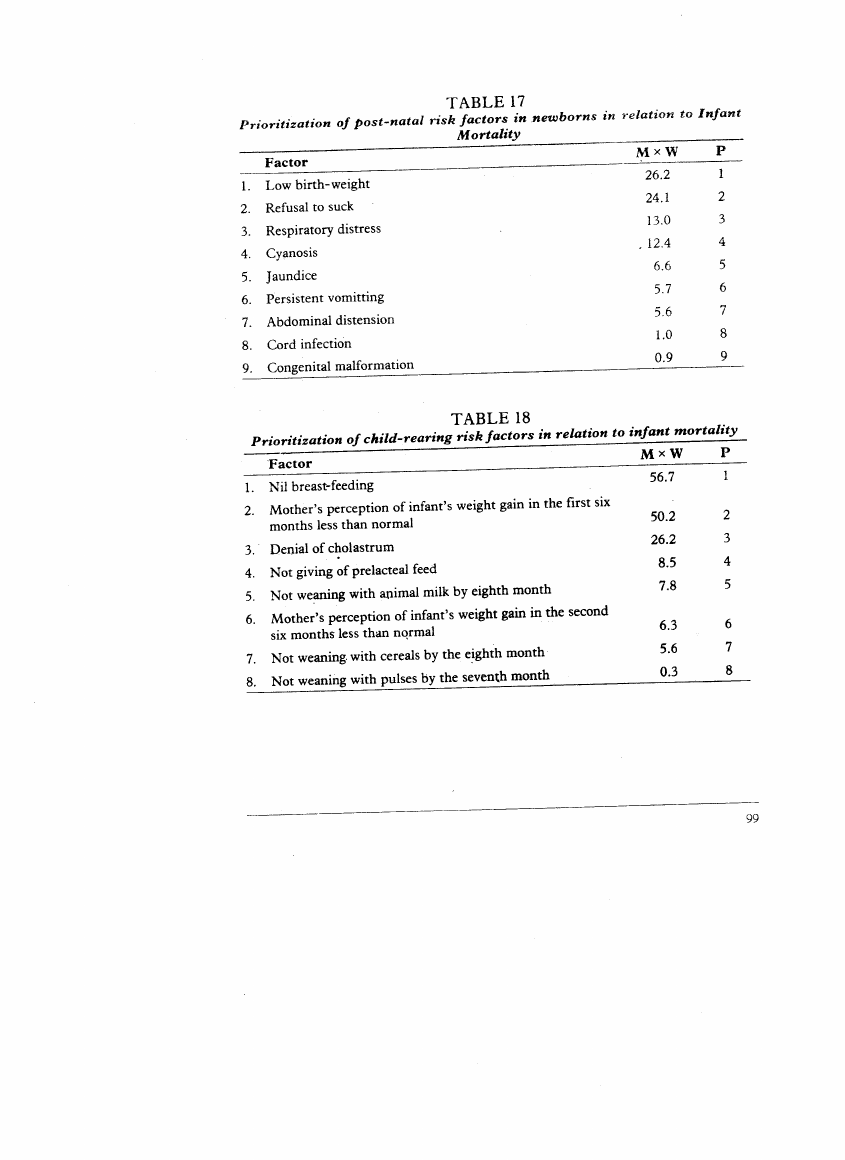

10.9 Page 99 |

▲back to top |

|

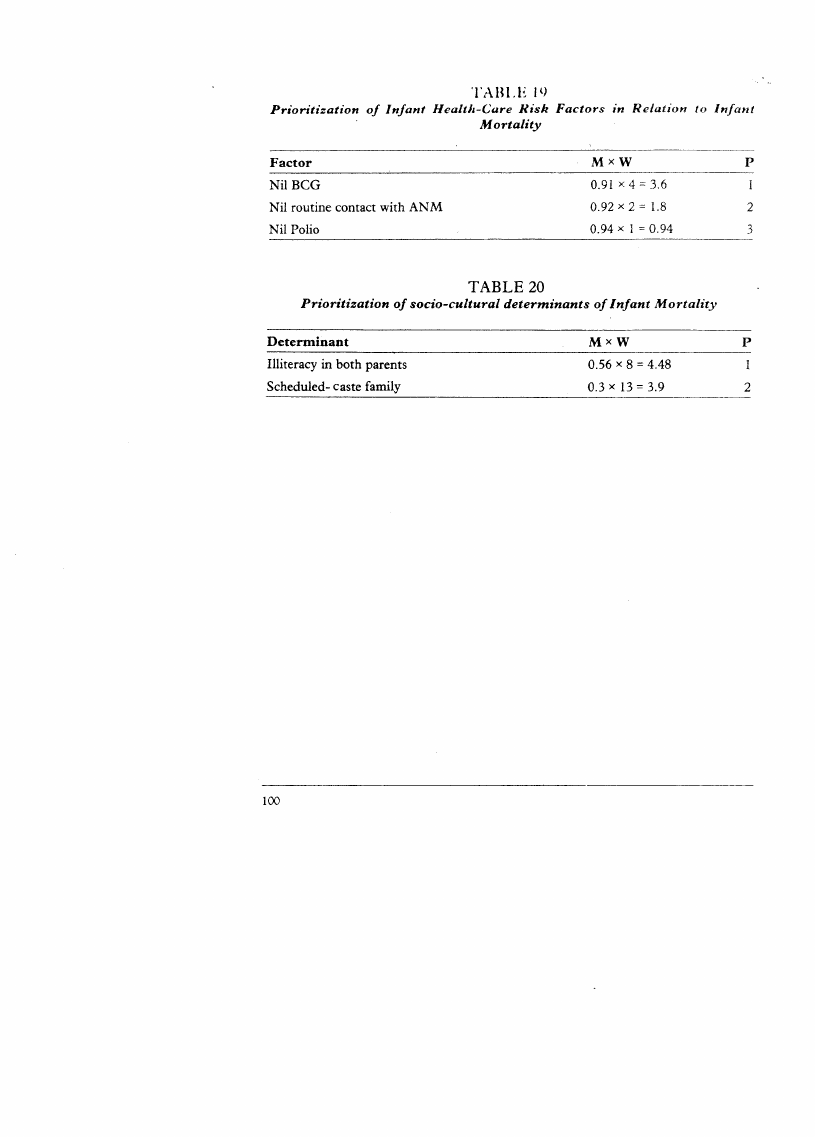

10.10 Page 100 |

▲back to top |

|

11 Pages 101-110 |

▲back to top |

|

11.1 Page 101 |

▲back to top |

|

11.2 Page 102 |

▲back to top |

|

11.3 Page 103 |

▲back to top |

|

11.4 Page 104 |

▲back to top |

|

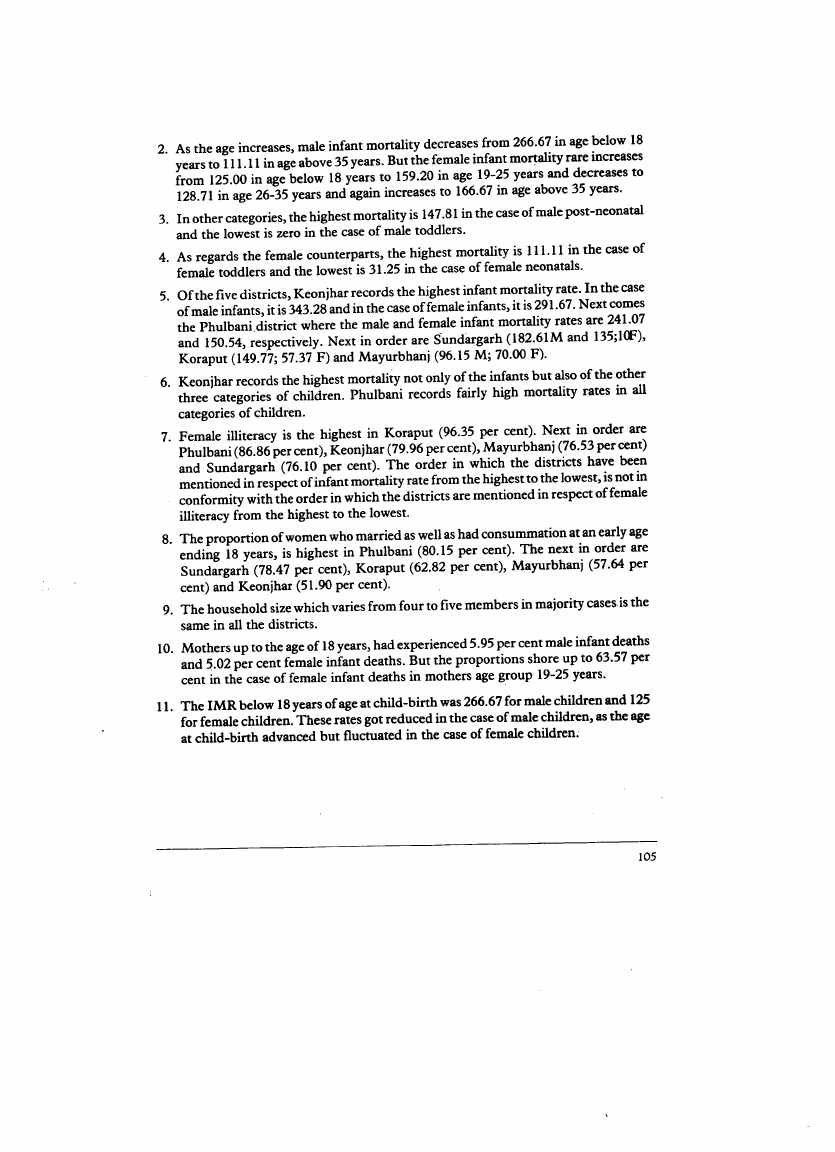

11.5 Page 105 |

▲back to top |

|

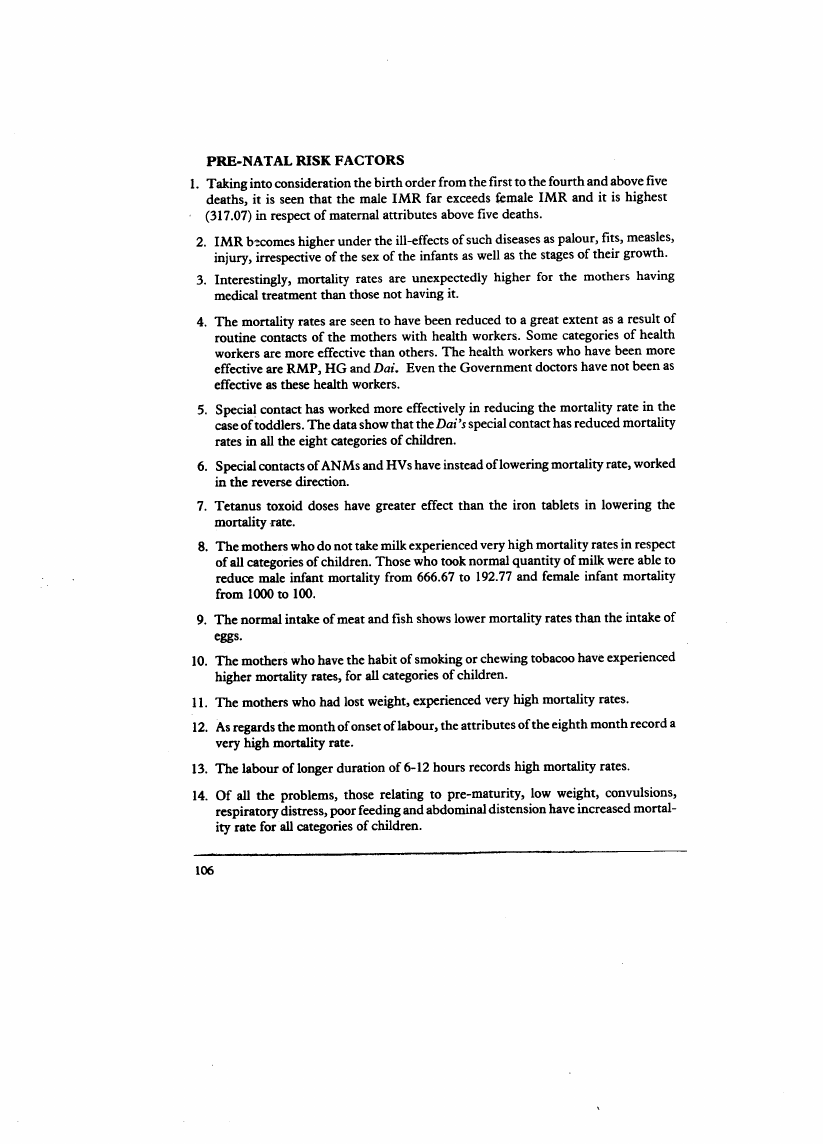

11.6 Page 106 |

▲back to top |

|

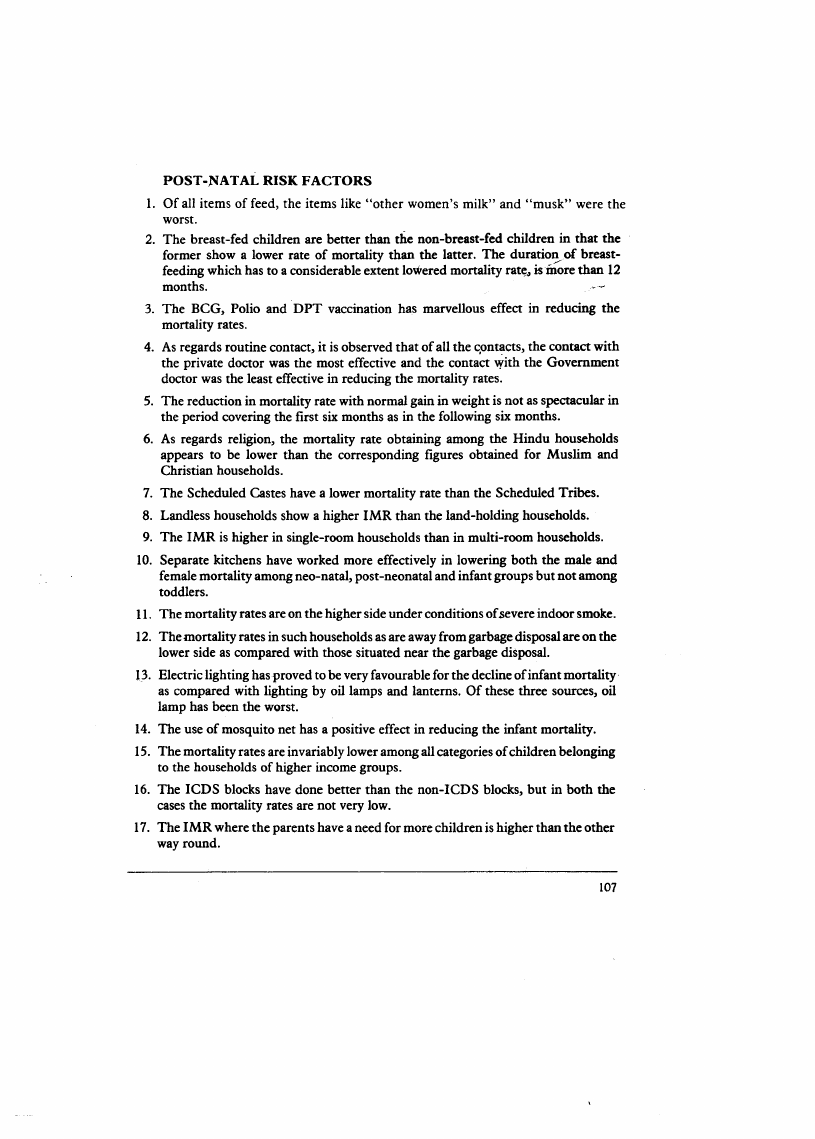

11.7 Page 107 |

▲back to top |

|

11.8 Page 108 |

▲back to top |

|

11.9 Page 109 |

▲back to top |

|

11.10 Page 110 |

▲back to top |

|

12 Pages 111-120 |

▲back to top |

|

12.1 Page 111 |

▲back to top |

|

12.2 Page 112 |

▲back to top |

|

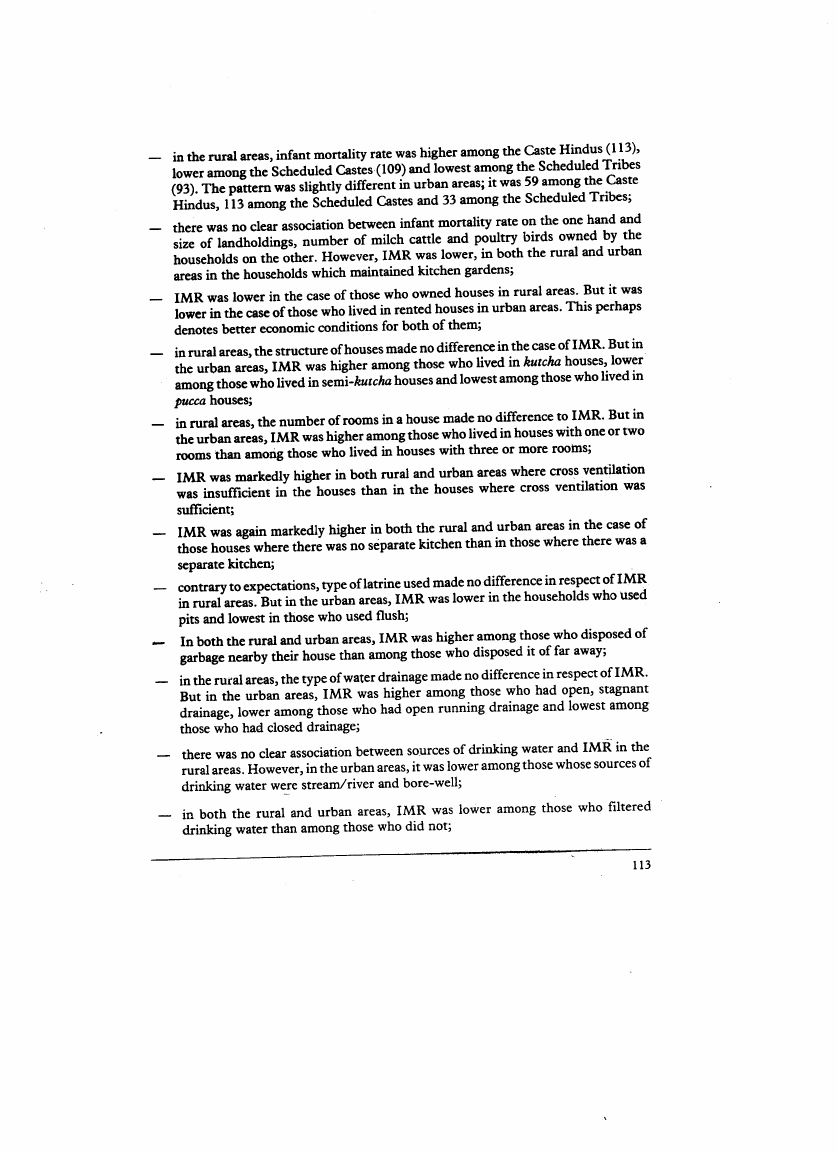

12.3 Page 113 |

▲back to top |

|

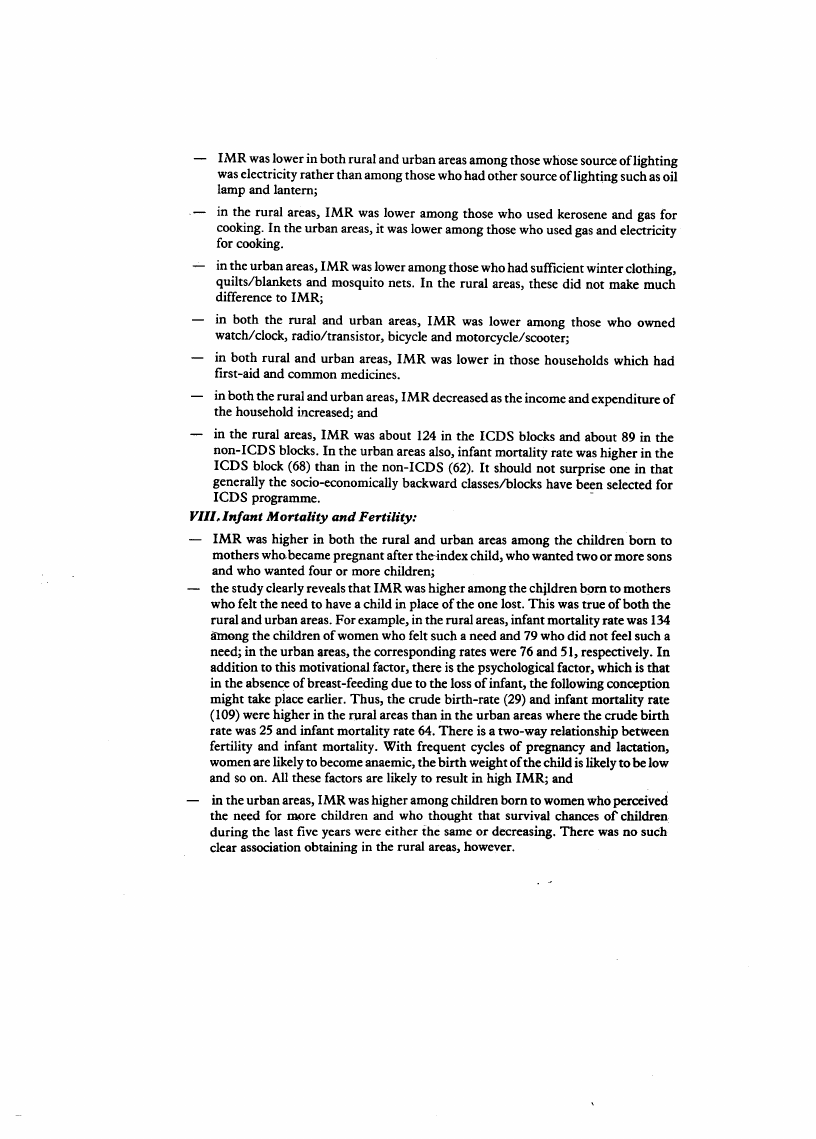

12.4 Page 114 |

▲back to top |

|

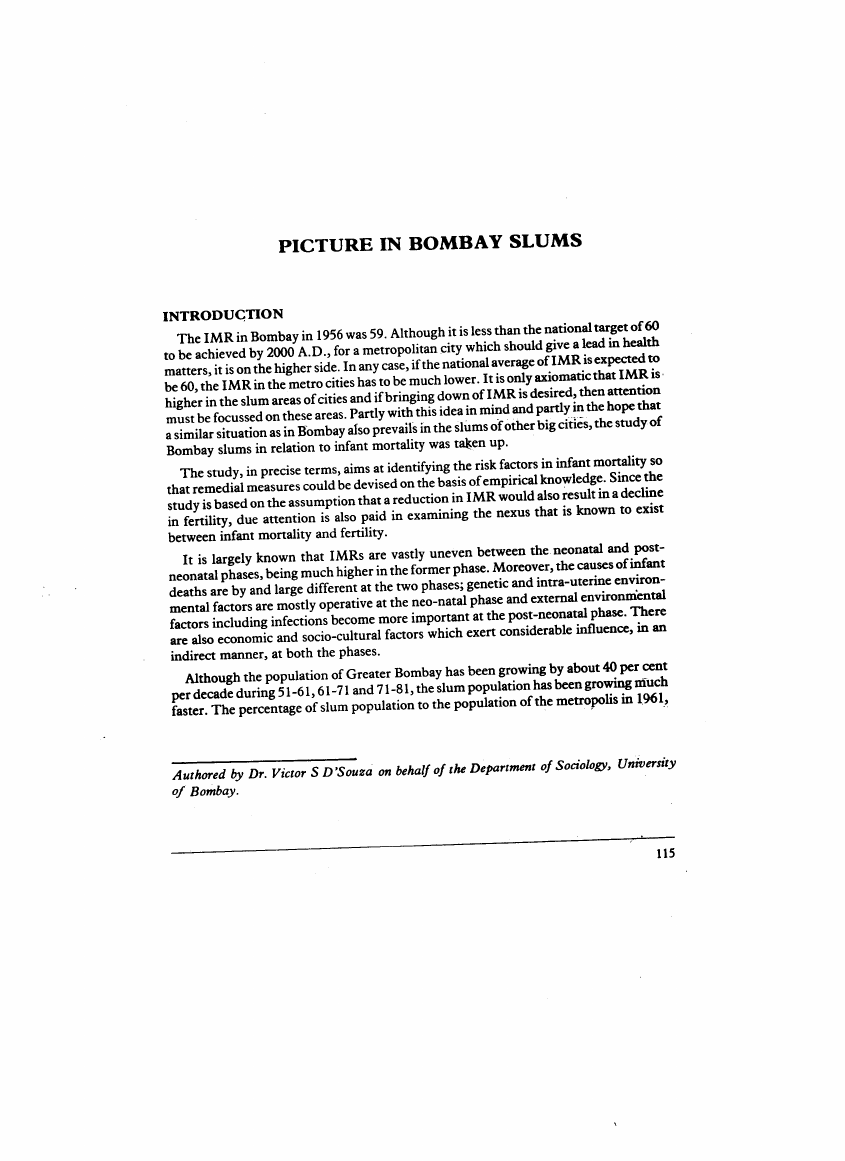

12.5 Page 115 |

▲back to top |

|

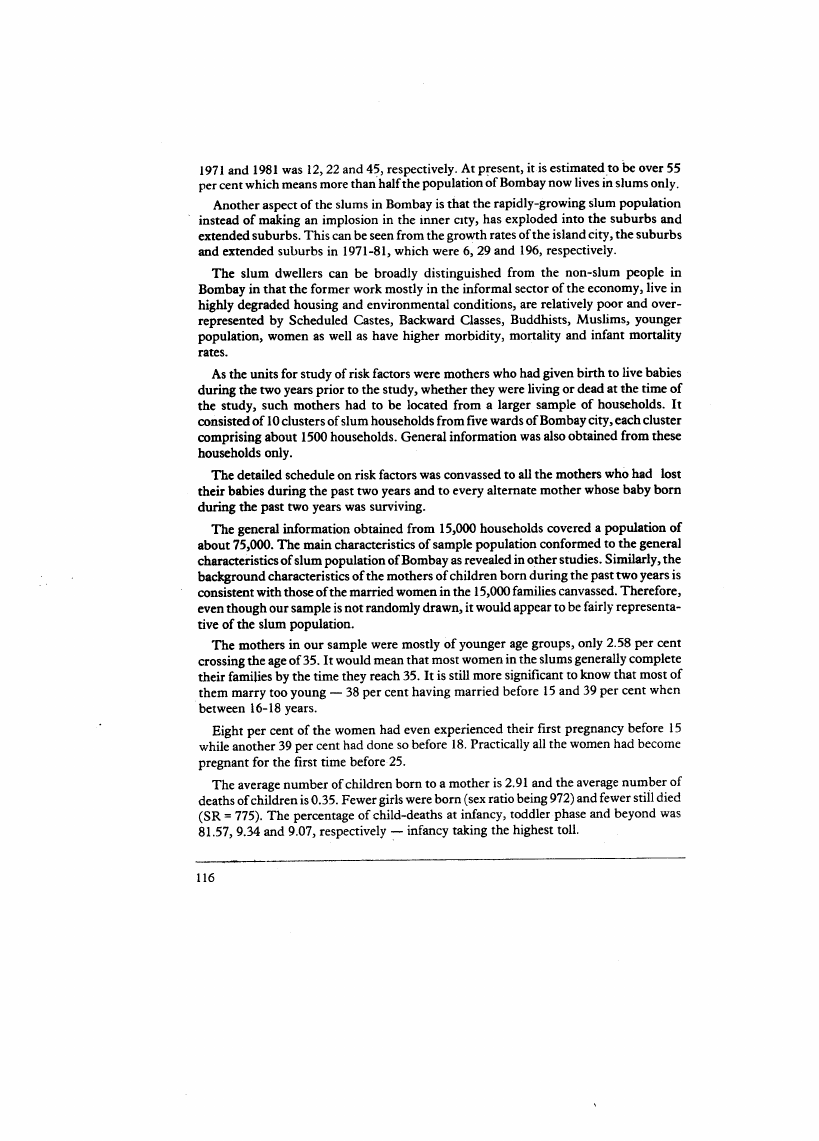

12.6 Page 116 |

▲back to top |

|

12.7 Page 117 |

▲back to top |

|

12.8 Page 118 |

▲back to top |

|

12.9 Page 119 |

▲back to top |

|

12.10 Page 120 |

▲back to top |

|

13 Pages 121-130 |

▲back to top |

|

13.1 Page 121 |

▲back to top |

|

13.2 Page 122 |

▲back to top |

|

13.3 Page 123 |

▲back to top |

|

13.4 Page 124 |

▲back to top |

|

13.5 Page 125 |

▲back to top |

|

13.6 Page 126 |

▲back to top |

|

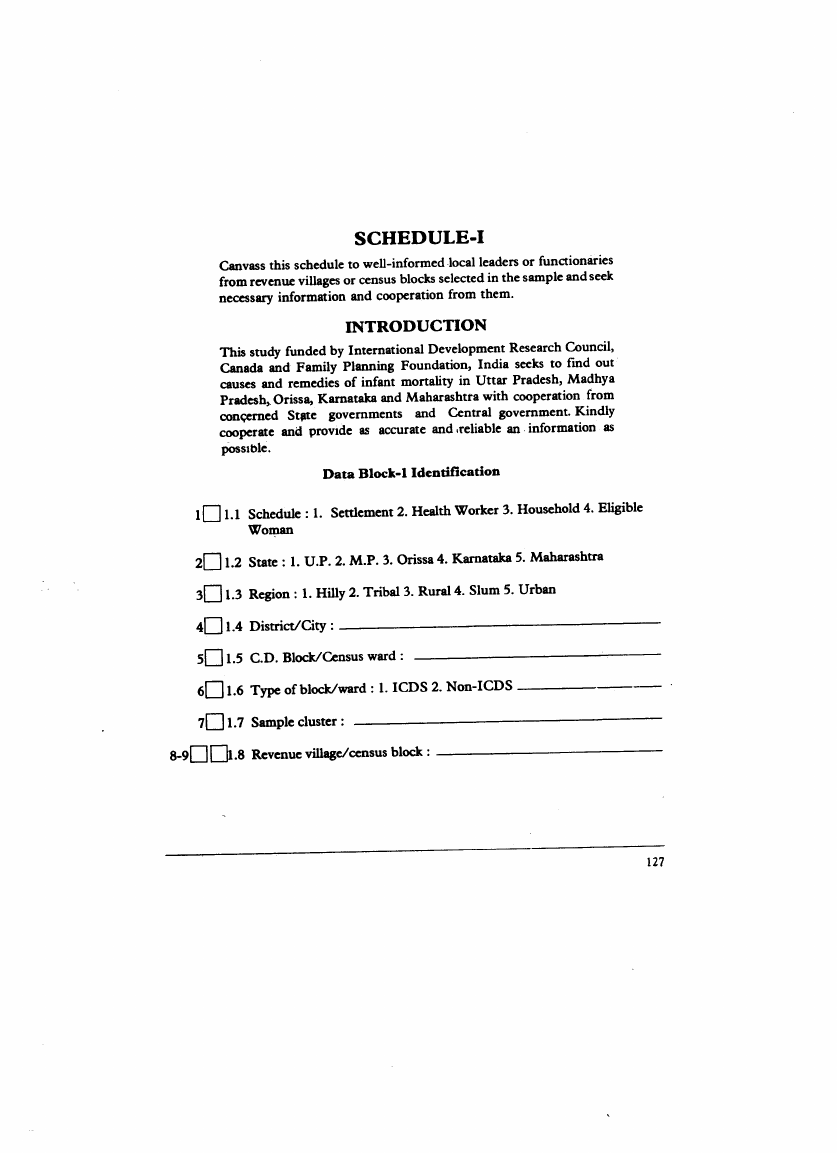

13.7 Page 127 |

▲back to top |

|

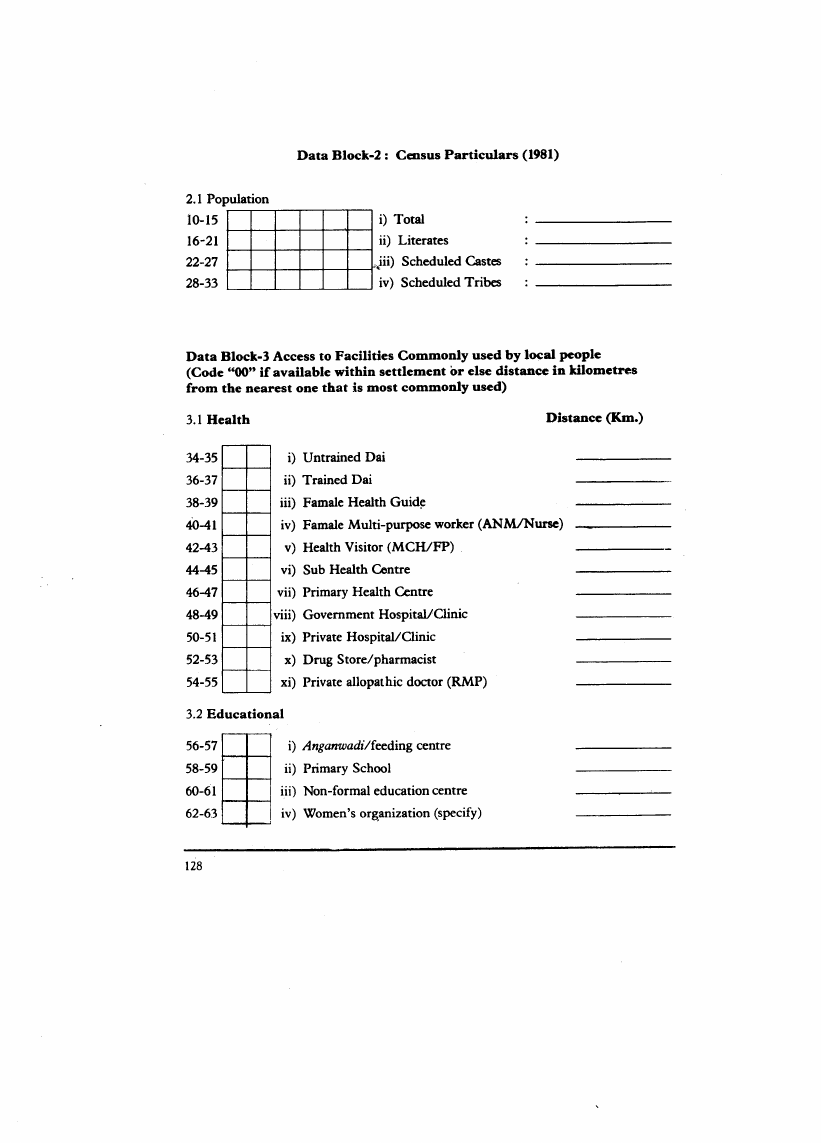

13.8 Page 128 |

▲back to top |

|

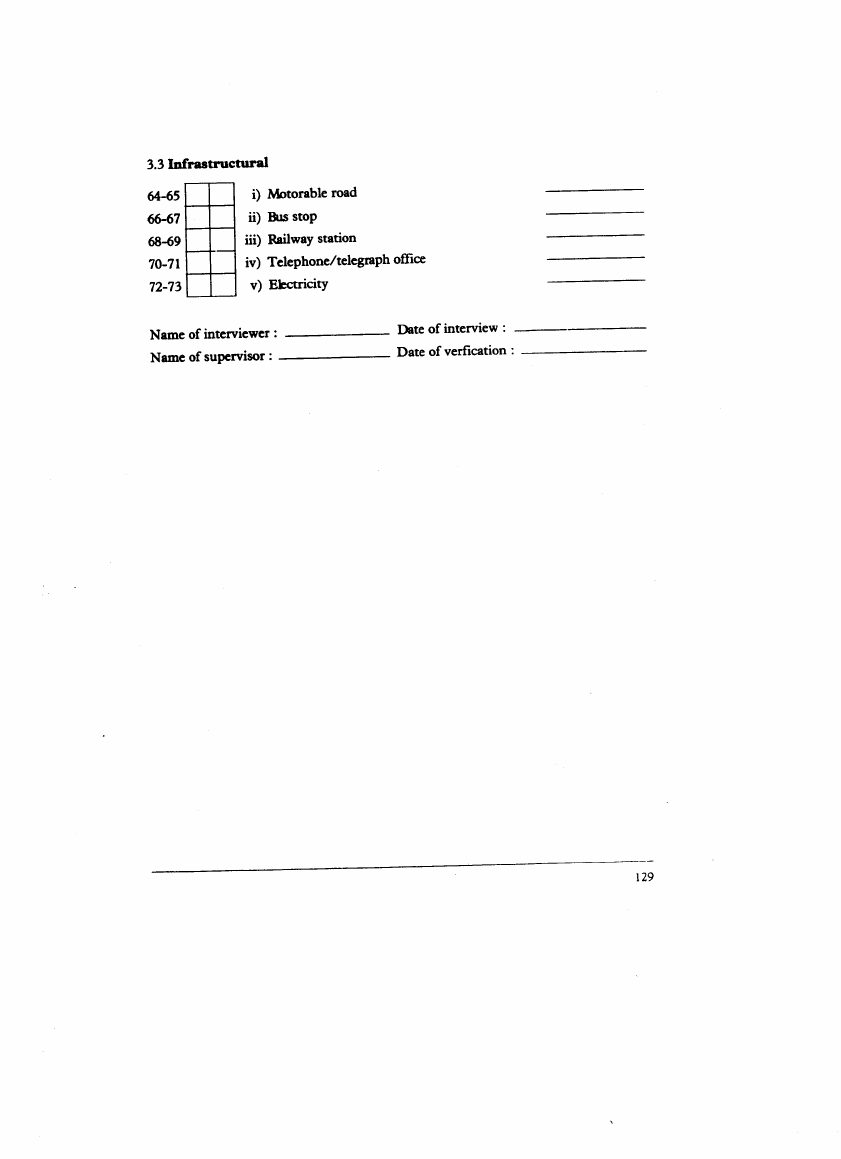

13.9 Page 129 |

▲back to top |

|

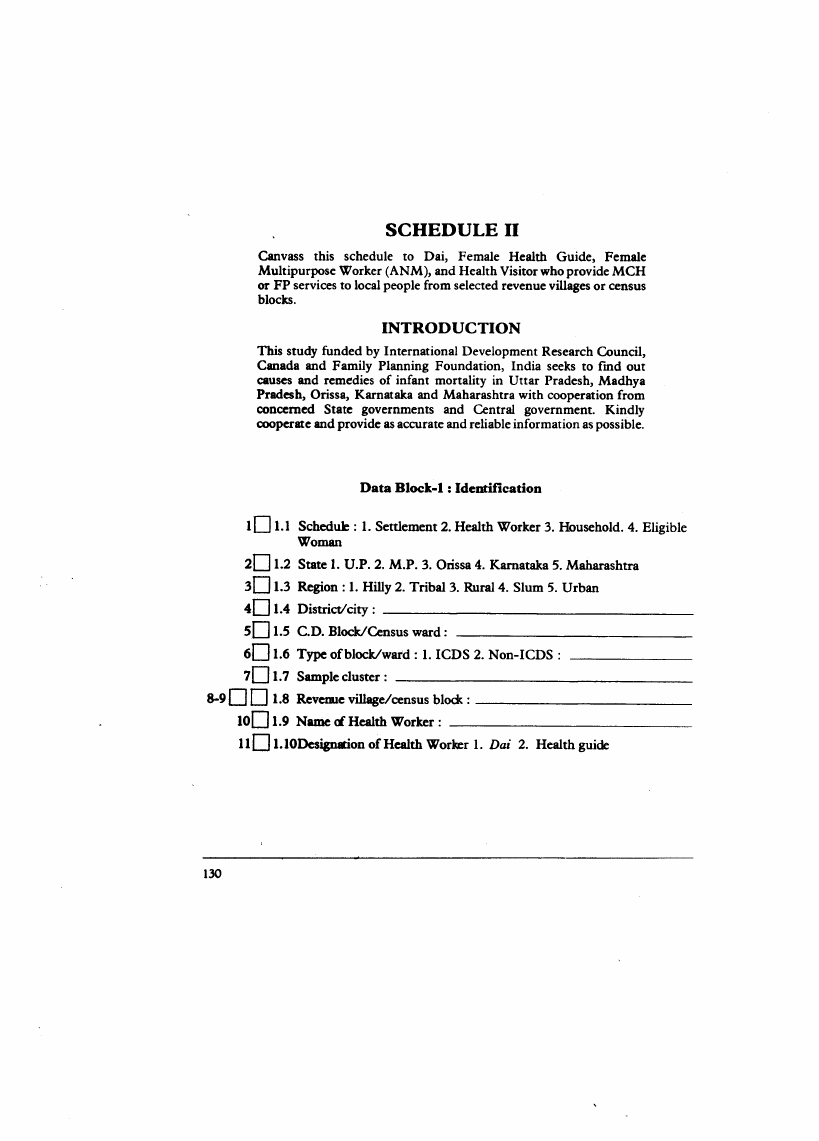

13.10 Page 130 |

▲back to top |

|

14 Pages 131-140 |

▲back to top |

|

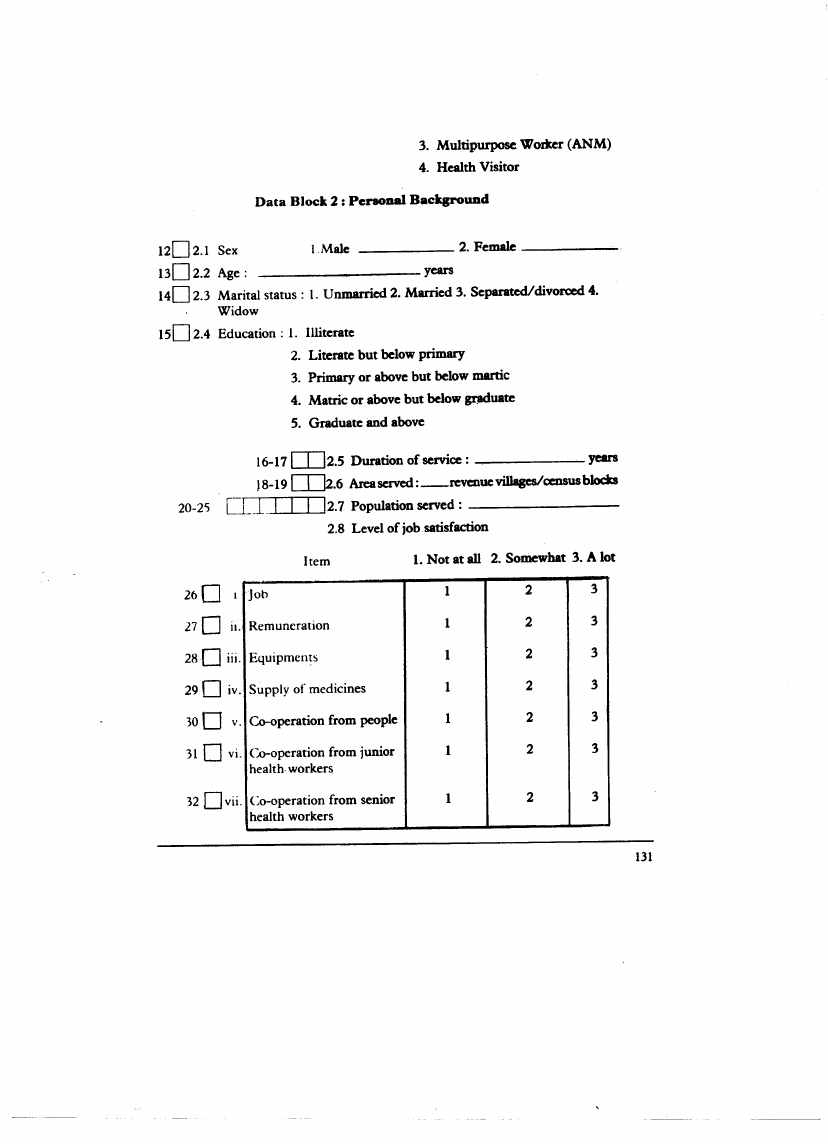

14.1 Page 131 |

▲back to top |

|

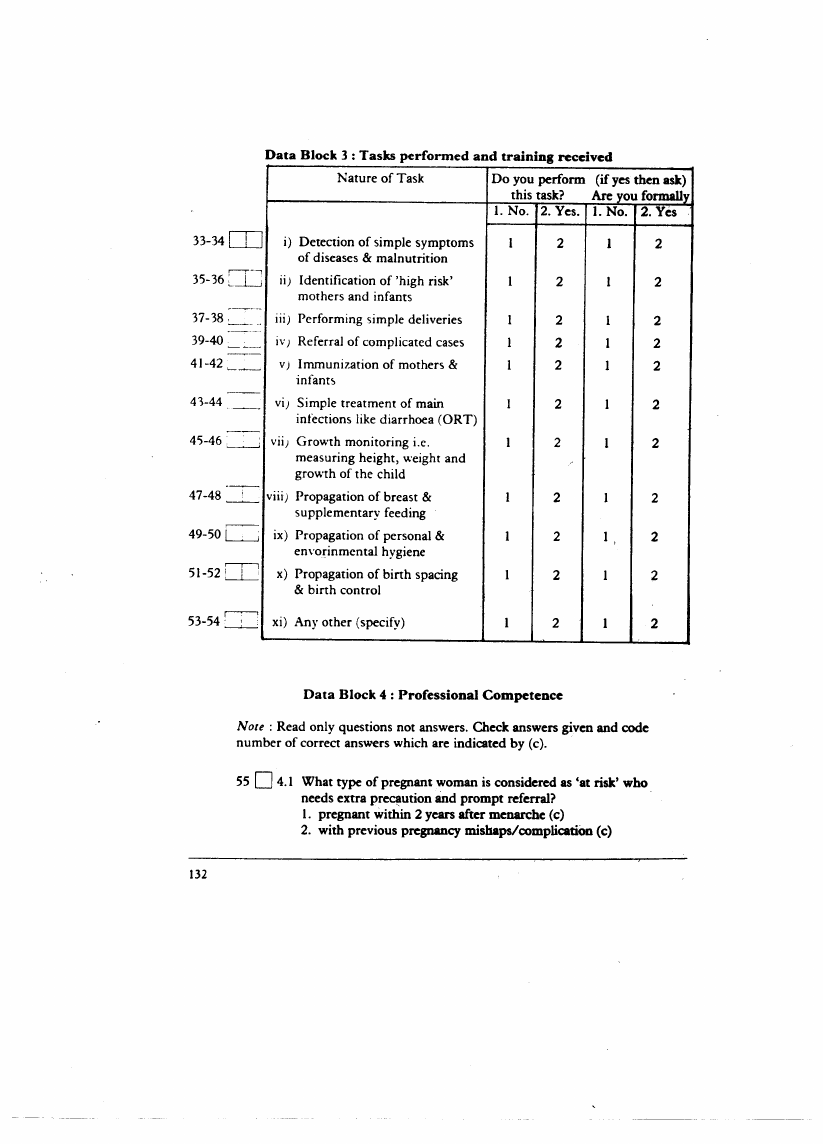

14.2 Page 132 |

▲back to top |

|

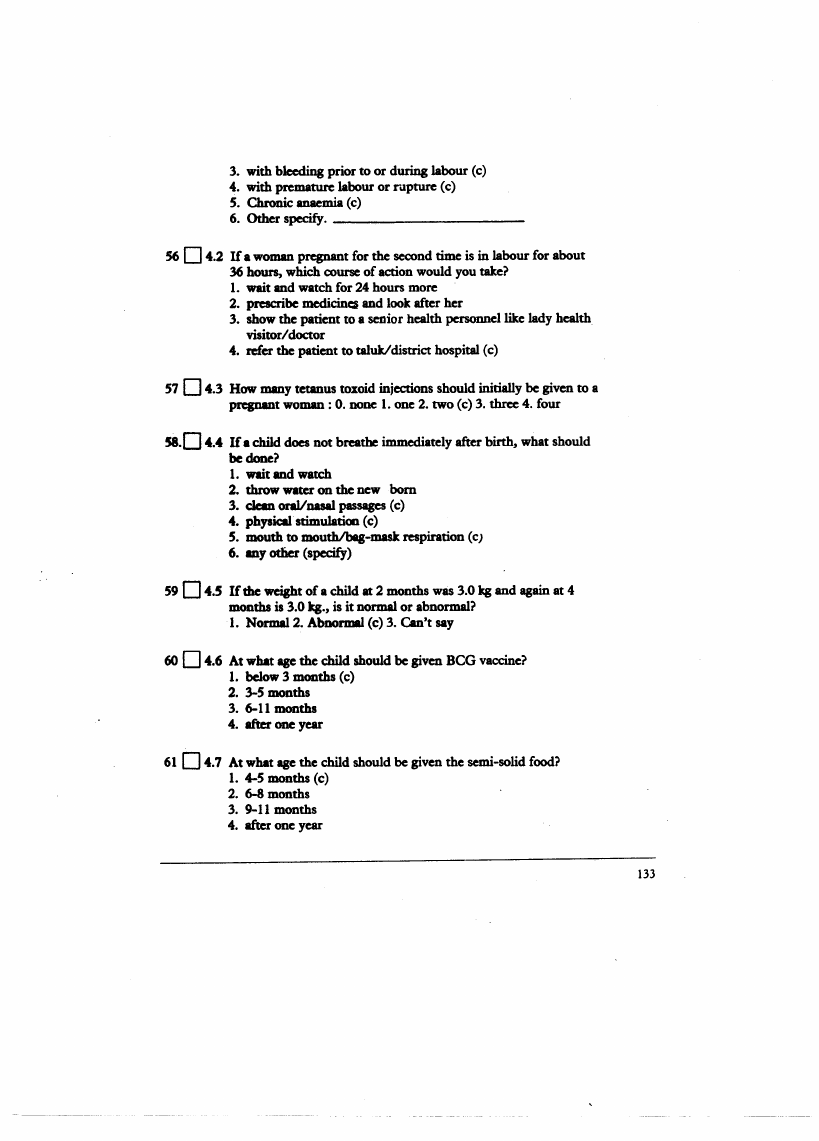

14.3 Page 133 |

▲back to top |

|

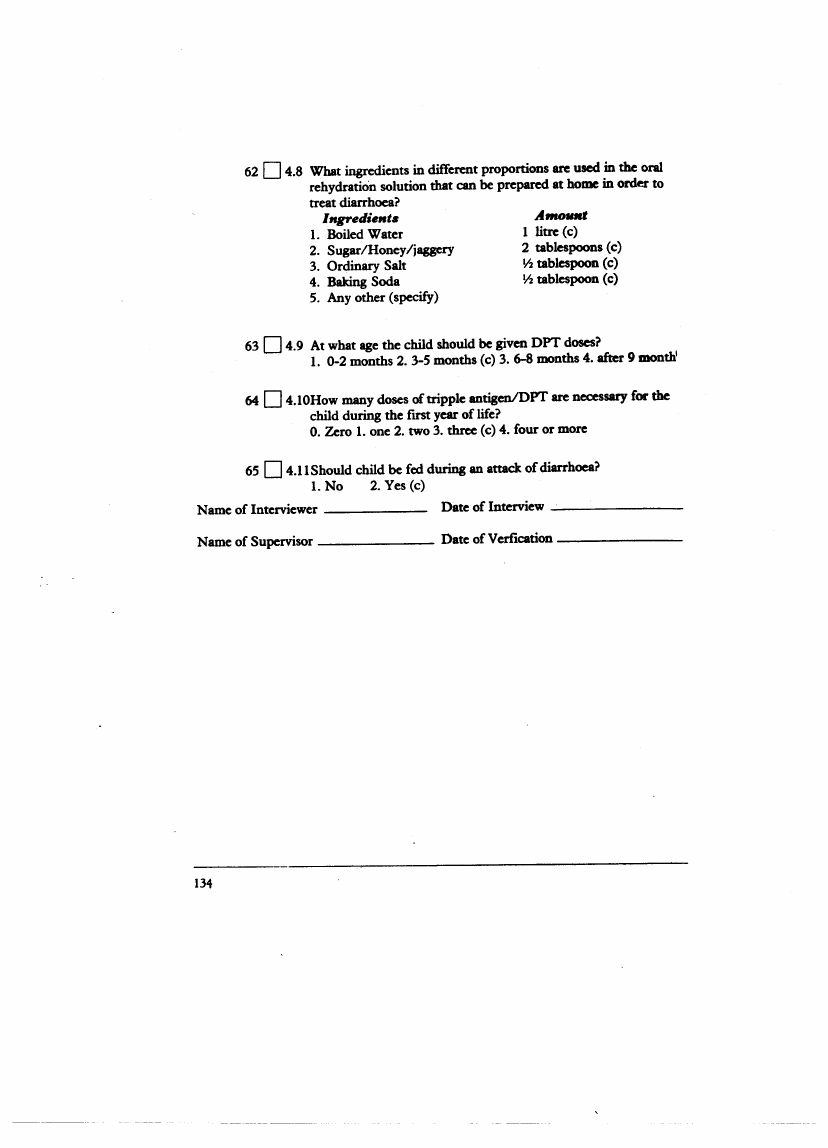

14.4 Page 134 |

▲back to top |

|

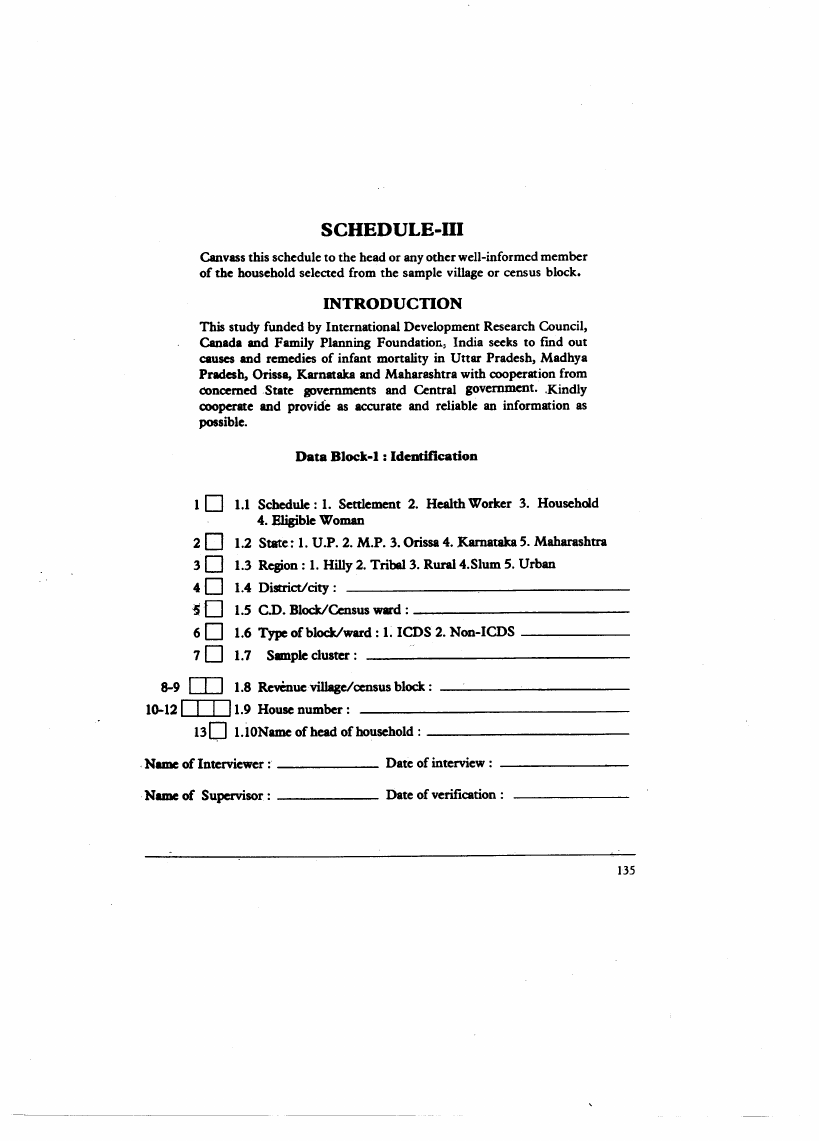

14.5 Page 135 |

▲back to top |

|

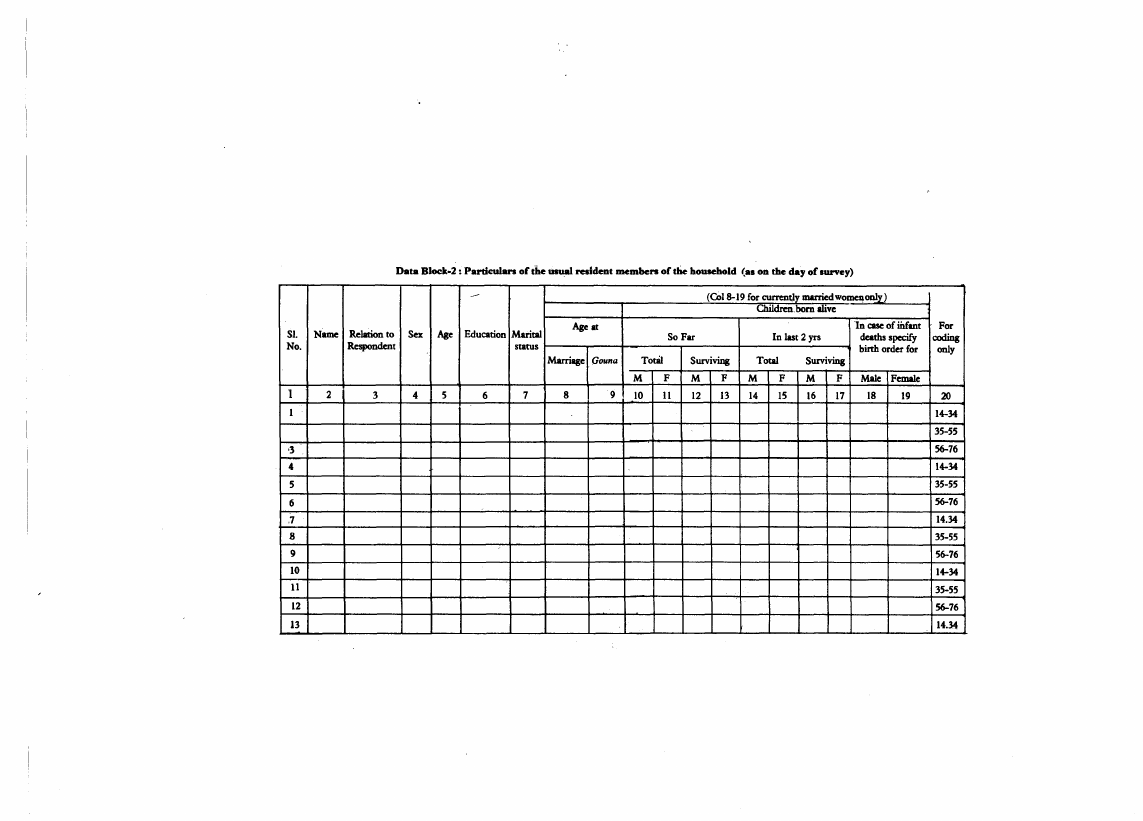

14.6 Page 136 |

▲back to top |

|

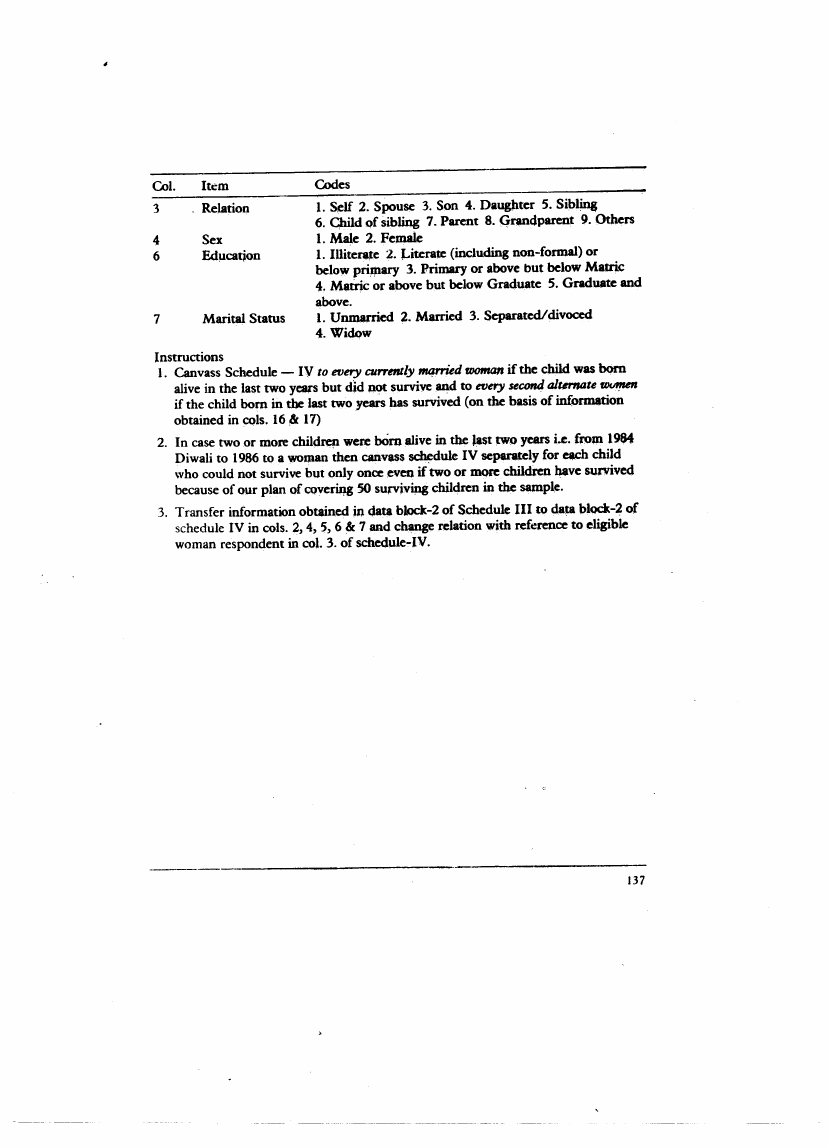

14.7 Page 137 |

▲back to top |

|

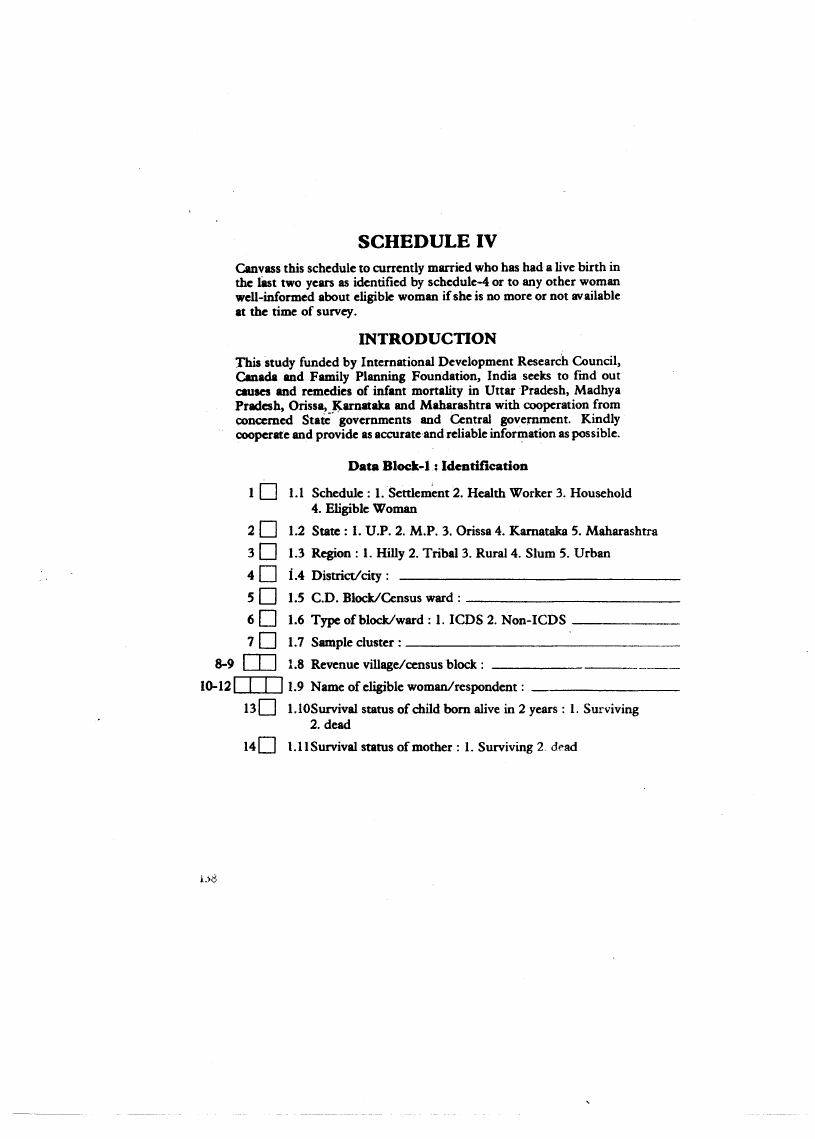

14.8 Page 138 |

▲back to top |

|

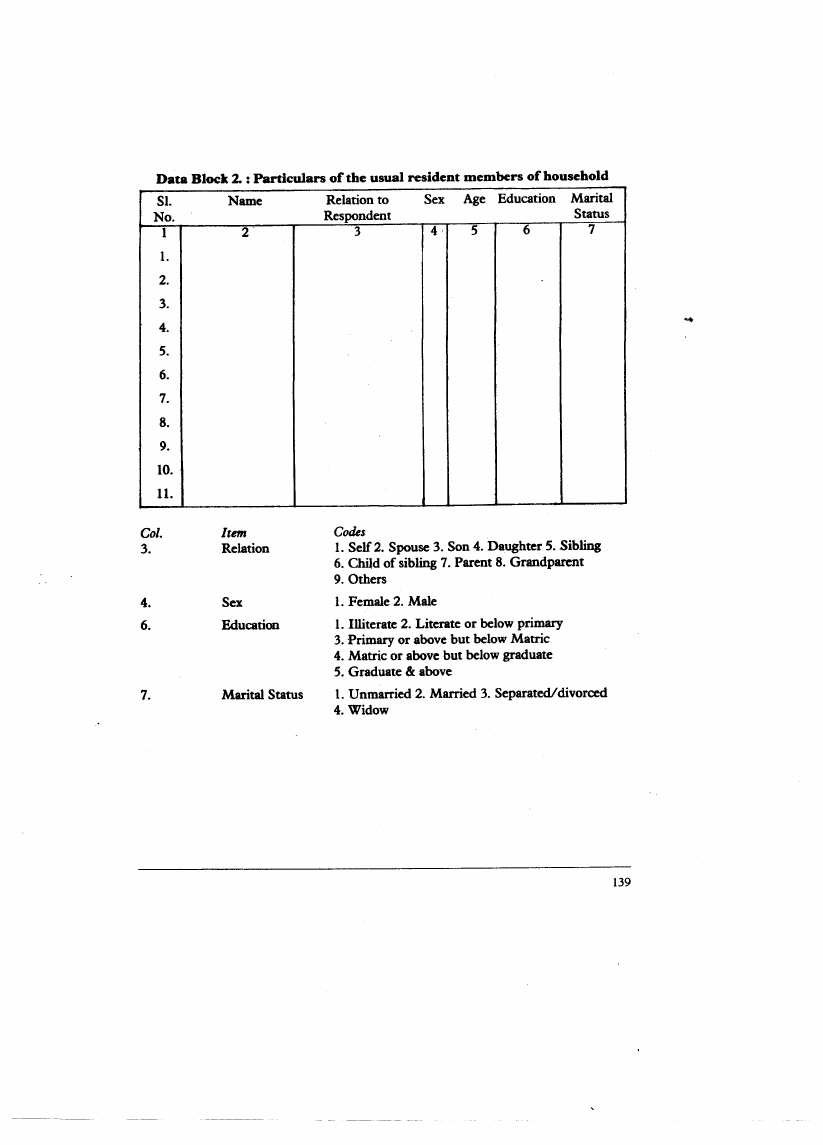

14.9 Page 139 |

▲back to top |

|

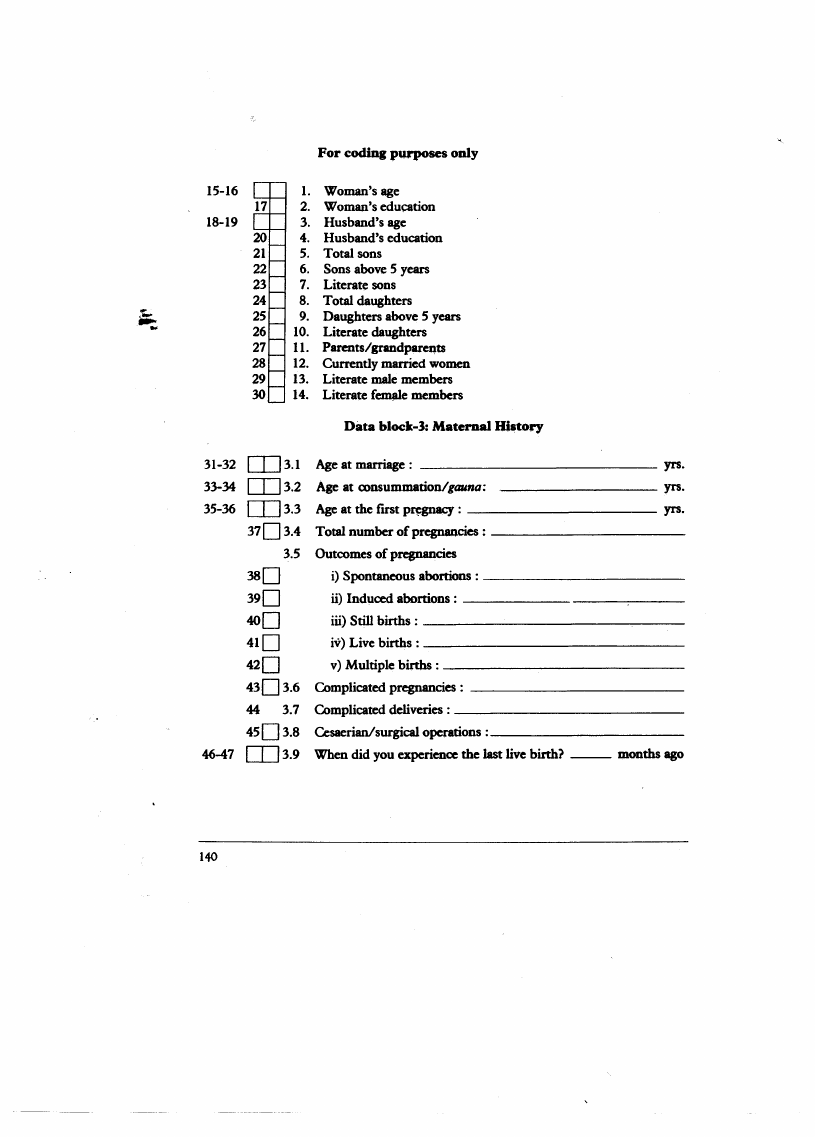

14.10 Page 140 |

▲back to top |

|

15 Pages 141-150 |

▲back to top |

|

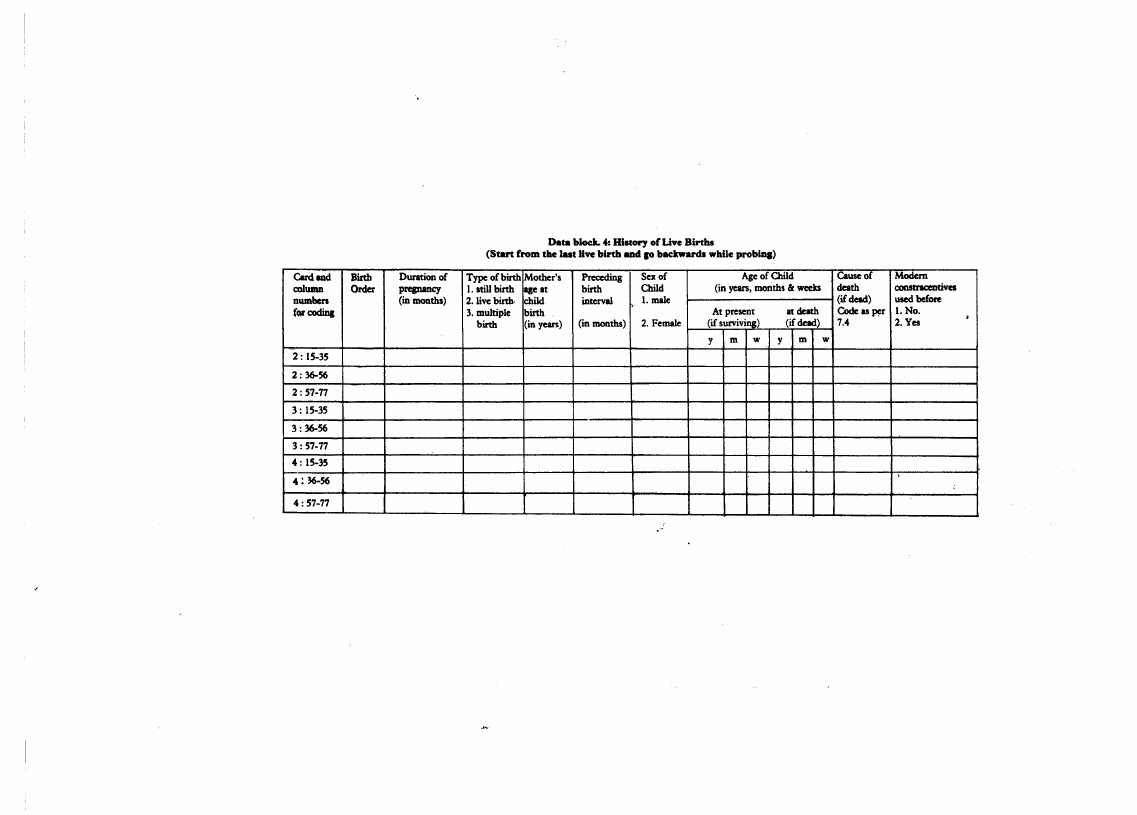

15.1 Page 141 |

▲back to top |

|

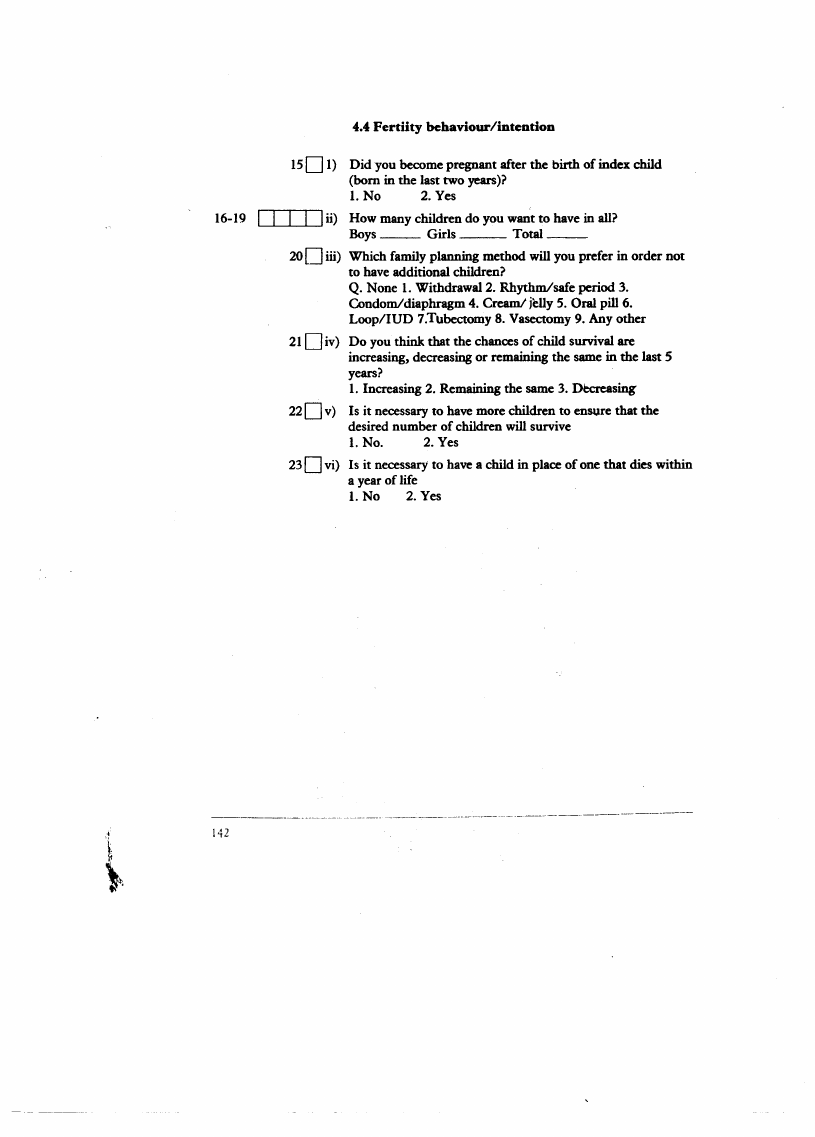

15.2 Page 142 |

▲back to top |

|

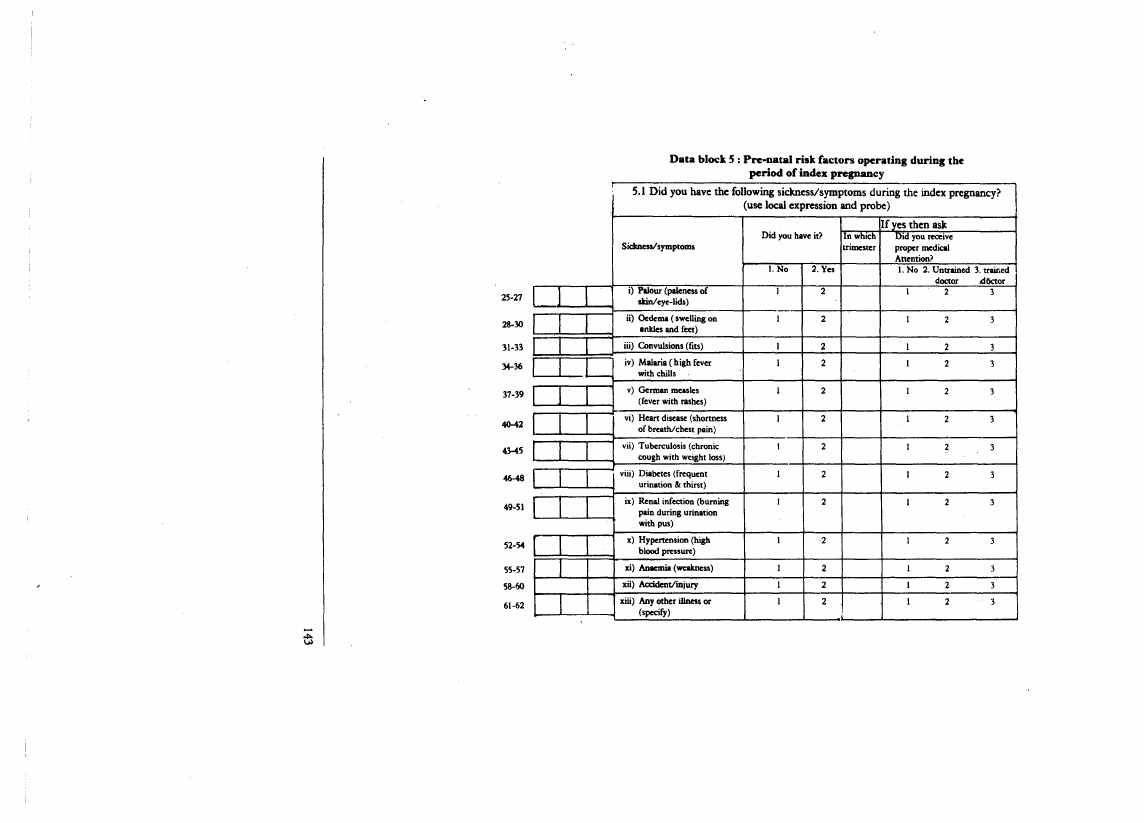

15.3 Page 143 |

▲back to top |

|

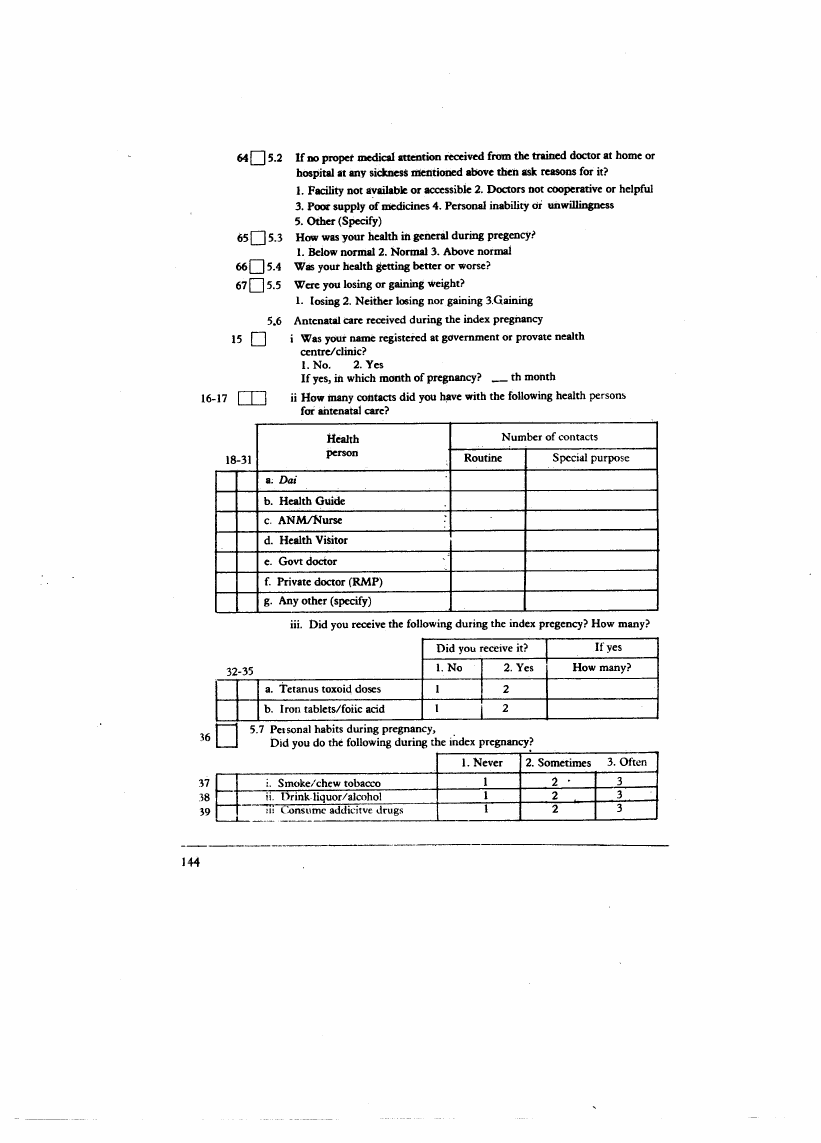

15.4 Page 144 |

▲back to top |

|

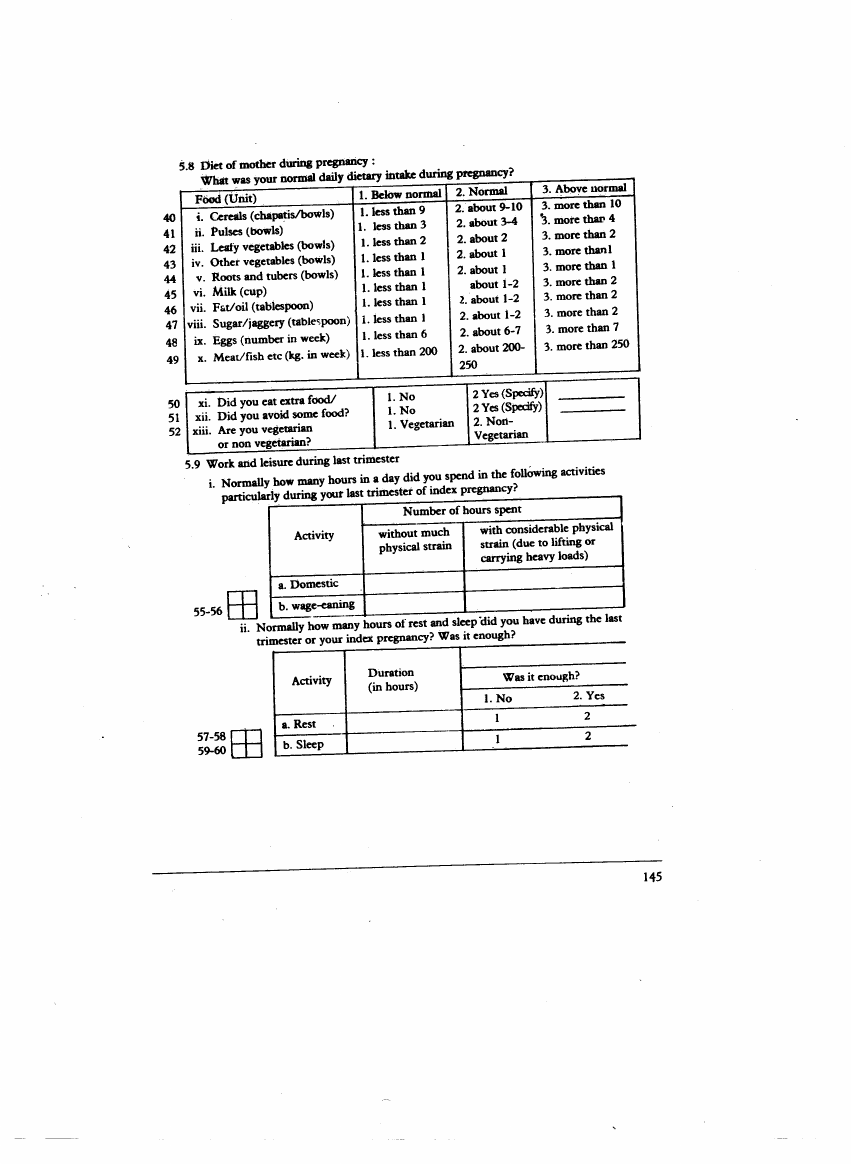

15.5 Page 145 |

▲back to top |

|

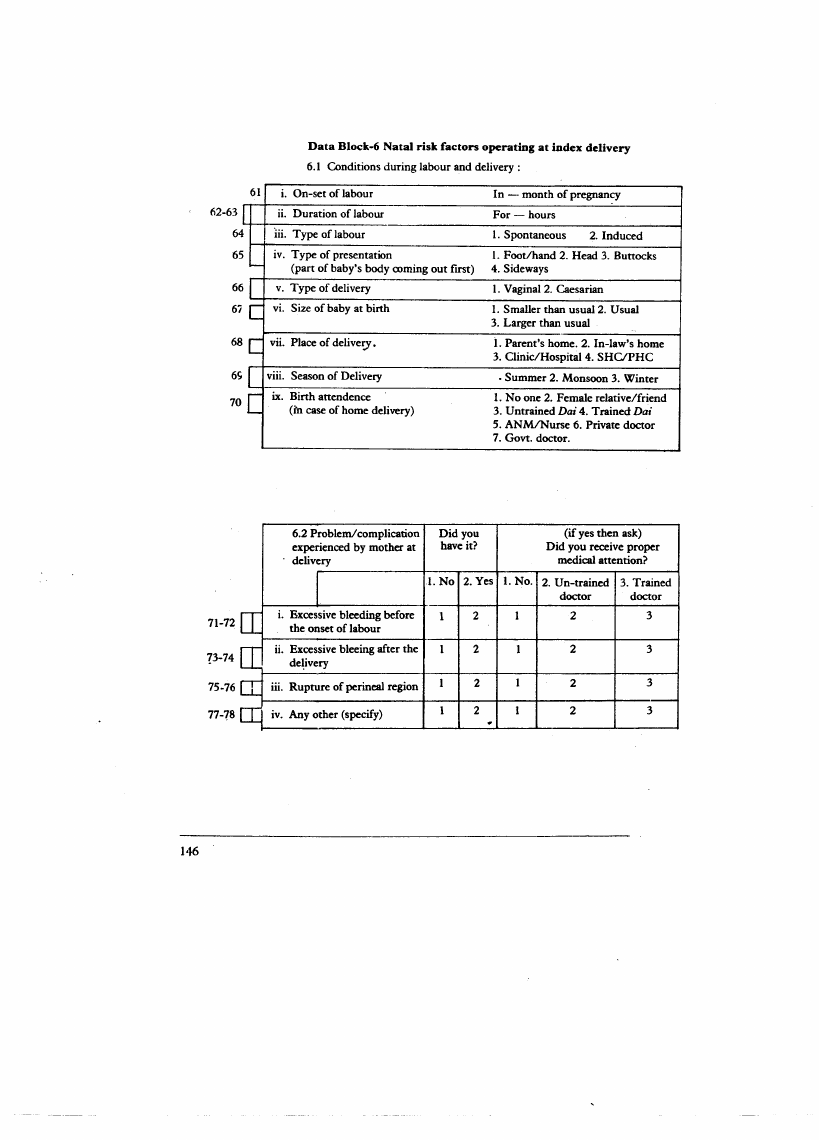

15.6 Page 146 |

▲back to top |

|

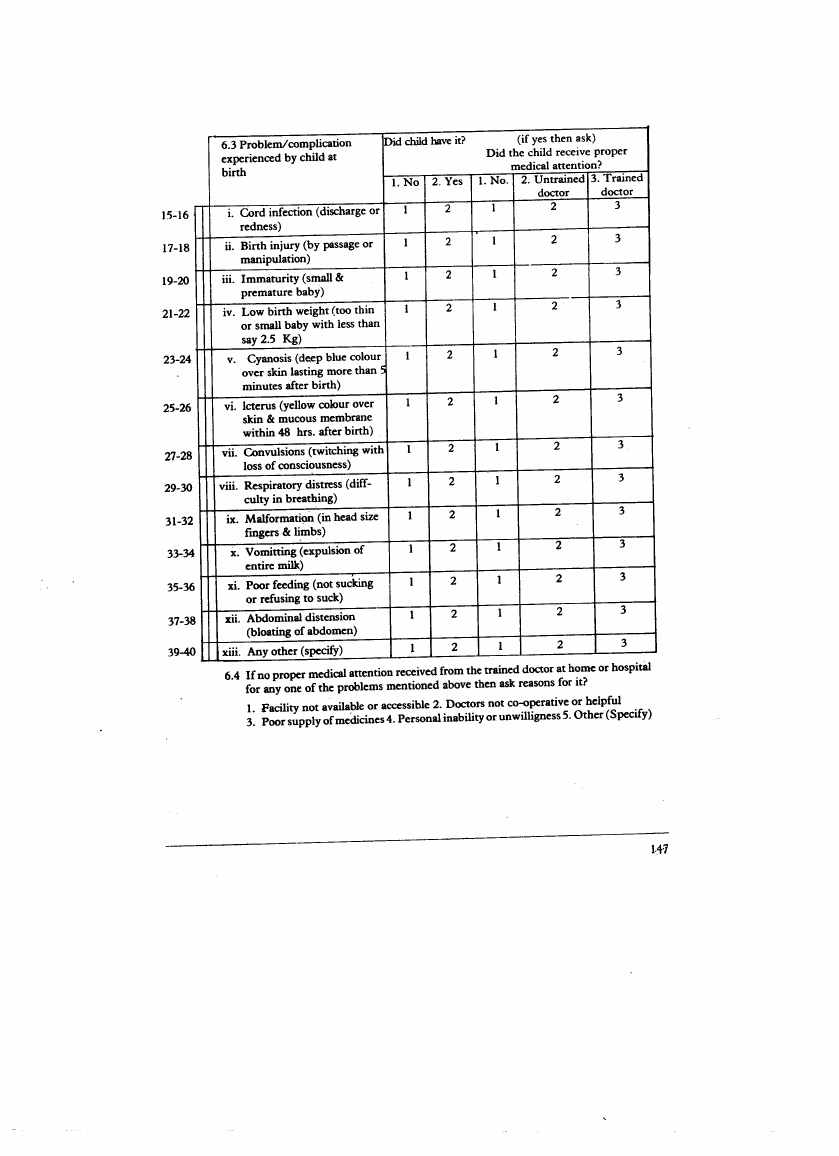

15.7 Page 147 |

▲back to top |

|

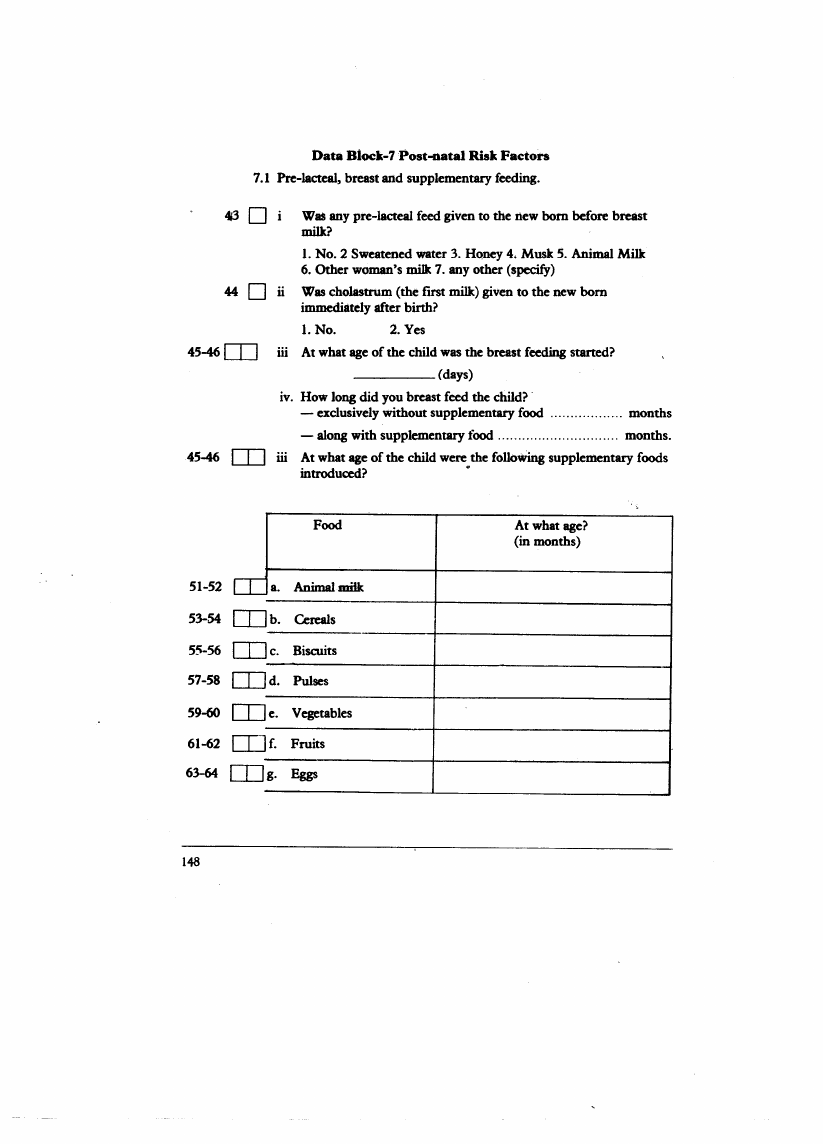

15.8 Page 148 |

▲back to top |

|

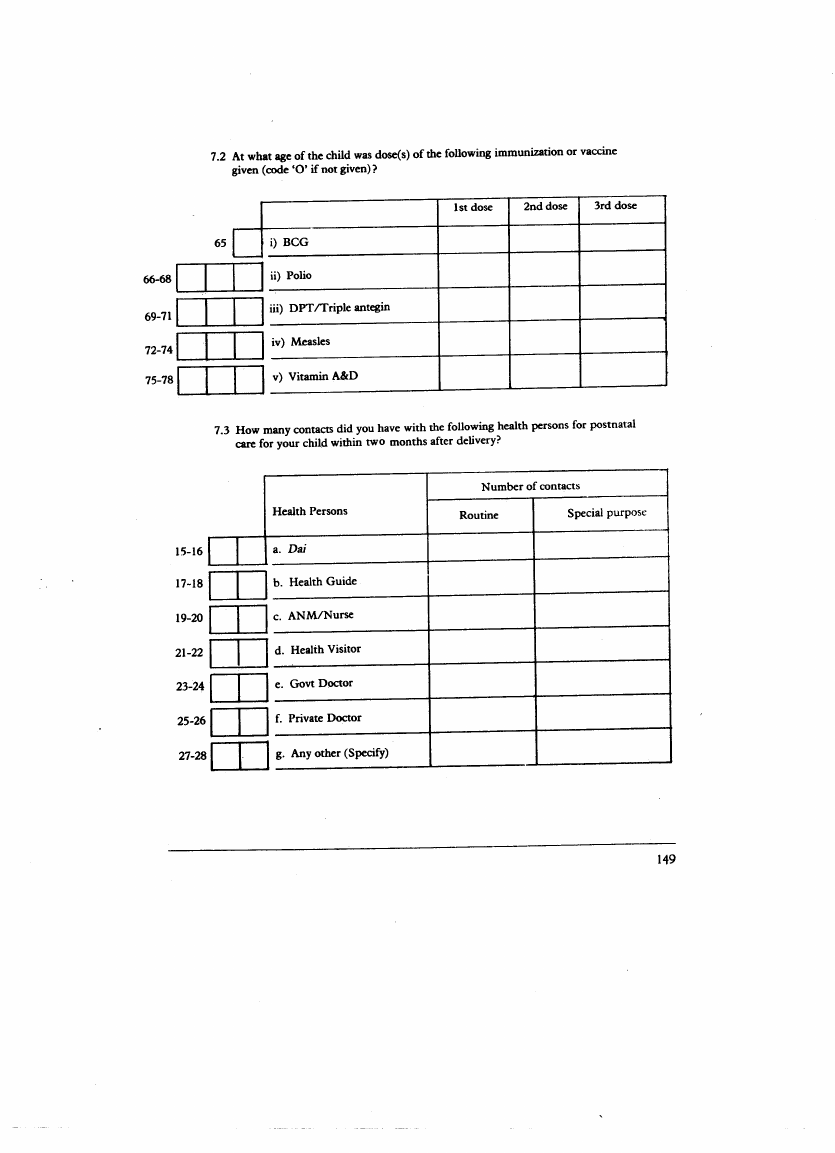

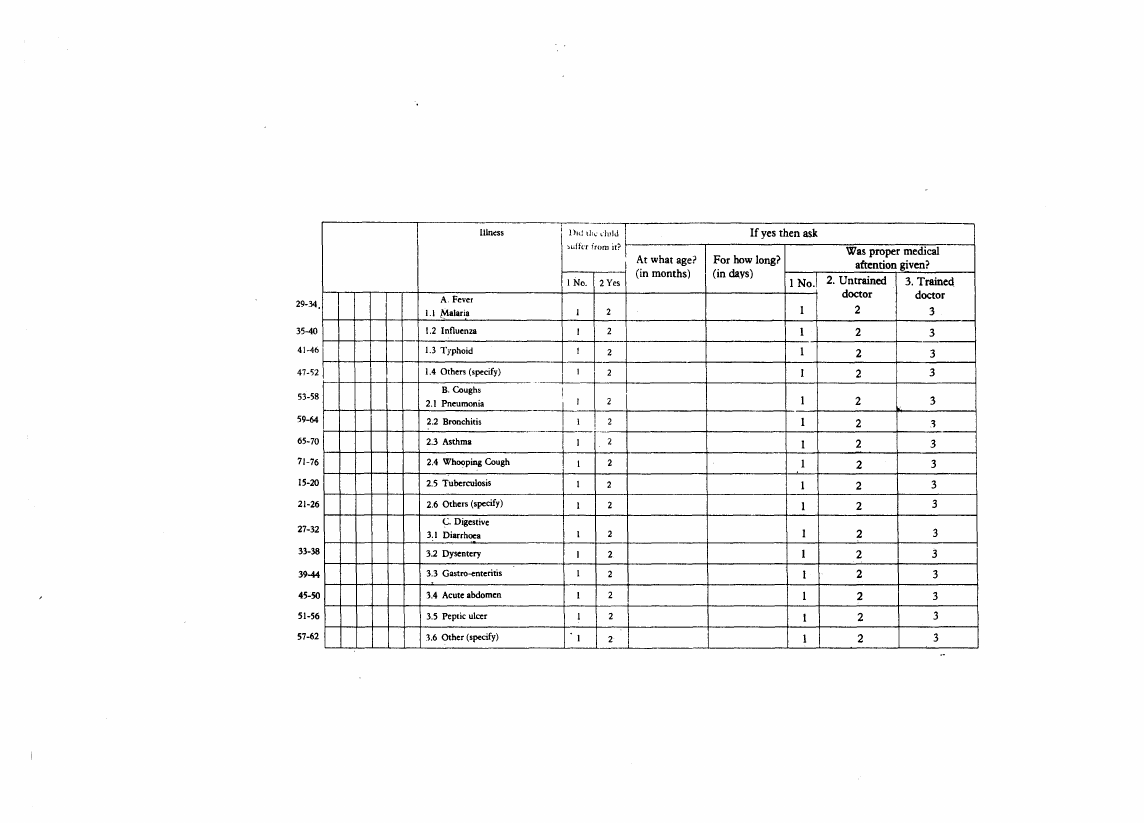

15.9 Page 149 |

▲back to top |

|

15.10 Page 150 |

▲back to top |

|

16 Pages 151-160 |

▲back to top |

|

16.1 Page 151 |

▲back to top |

|

16.2 Page 152 |

▲back to top |

|

16.3 Page 153 |

▲back to top |

|

16.4 Page 154 |

▲back to top |

|

16.5 Page 155 |

▲back to top |

|

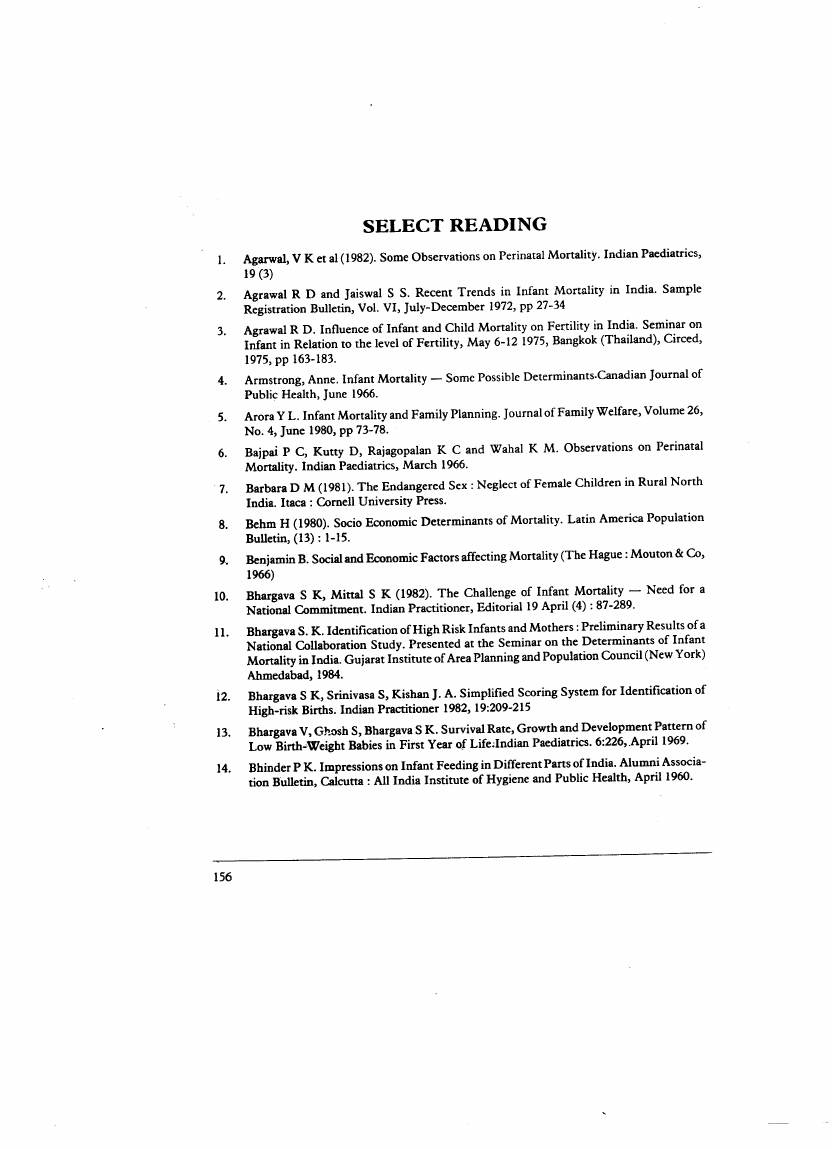

16.6 Page 156 |

▲back to top |

|

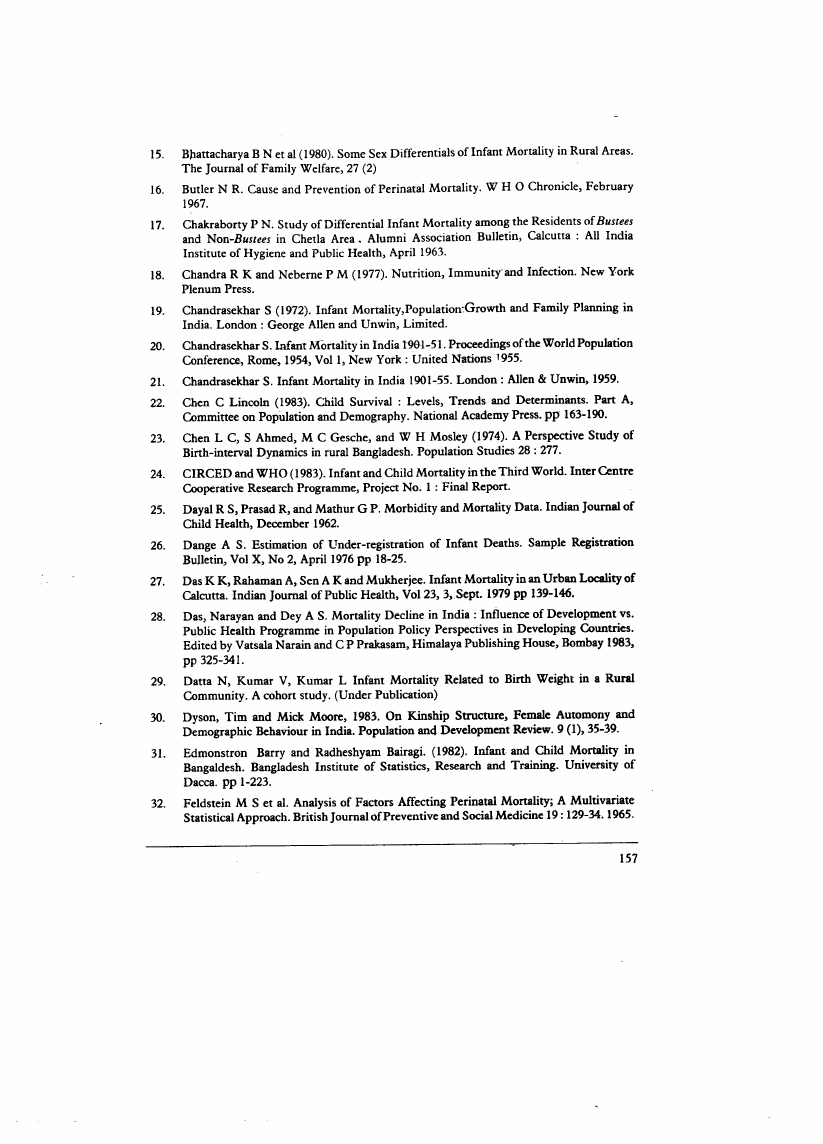

16.7 Page 157 |

▲back to top |

|

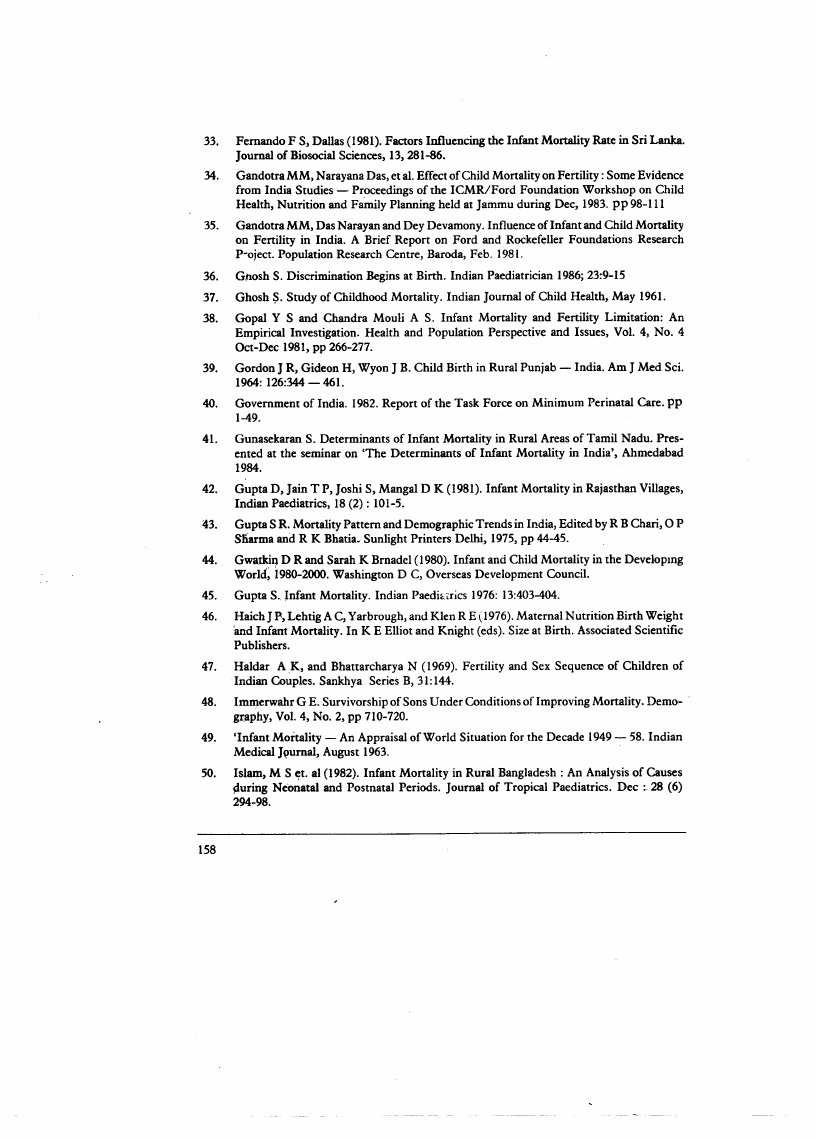

16.8 Page 158 |

▲back to top |

|

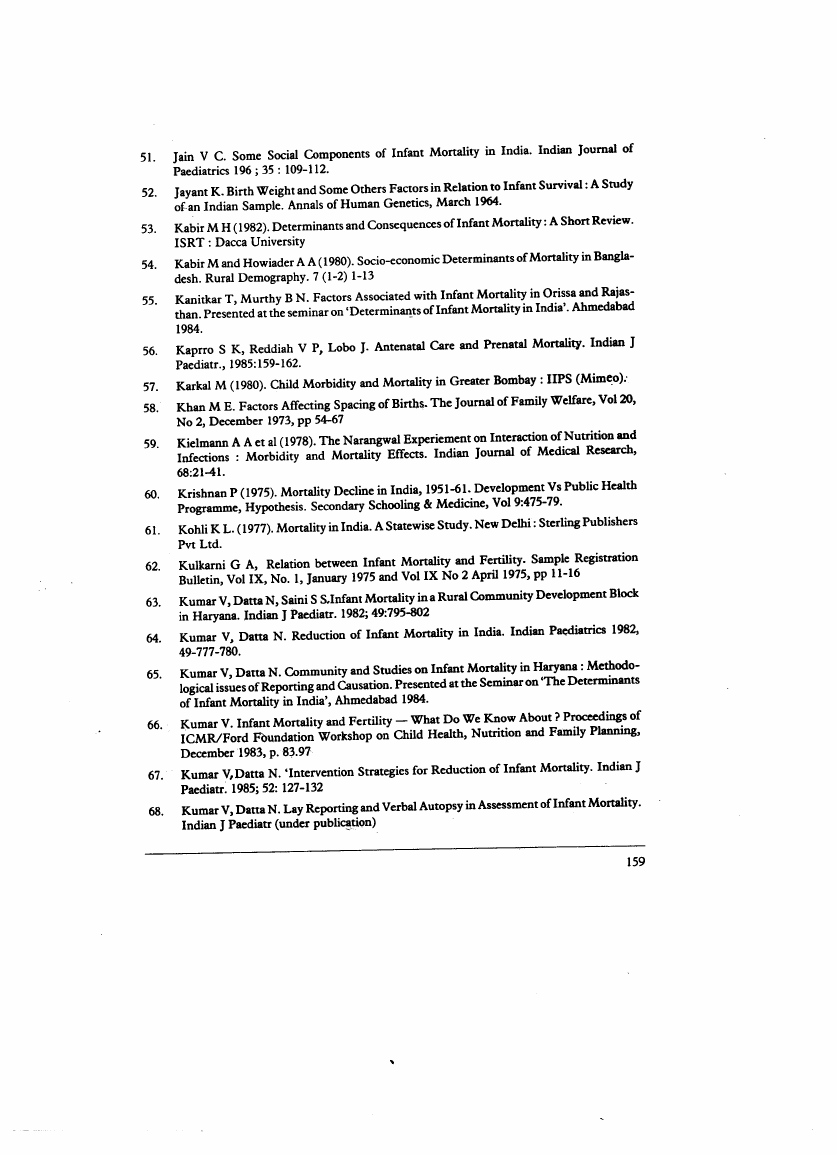

16.9 Page 159 |

▲back to top |

|

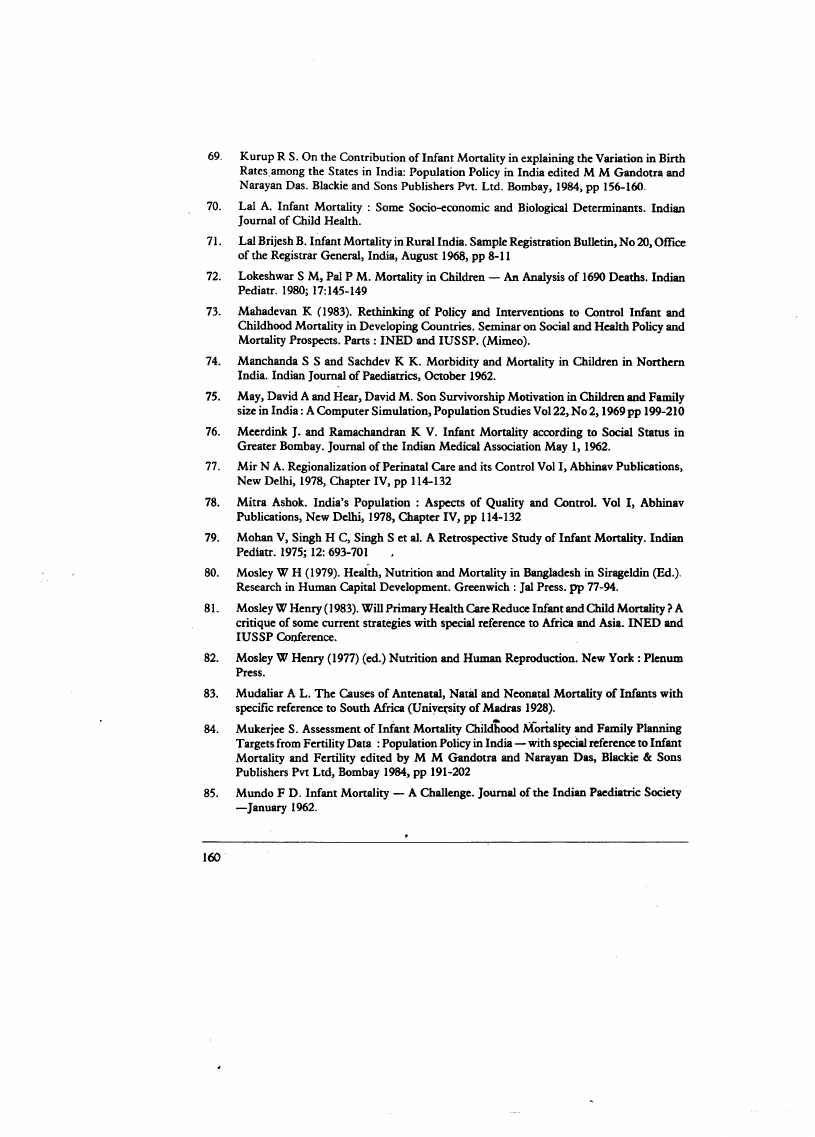

16.10 Page 160 |

▲back to top |

|

17 Pages 161-170 |

▲back to top |

|

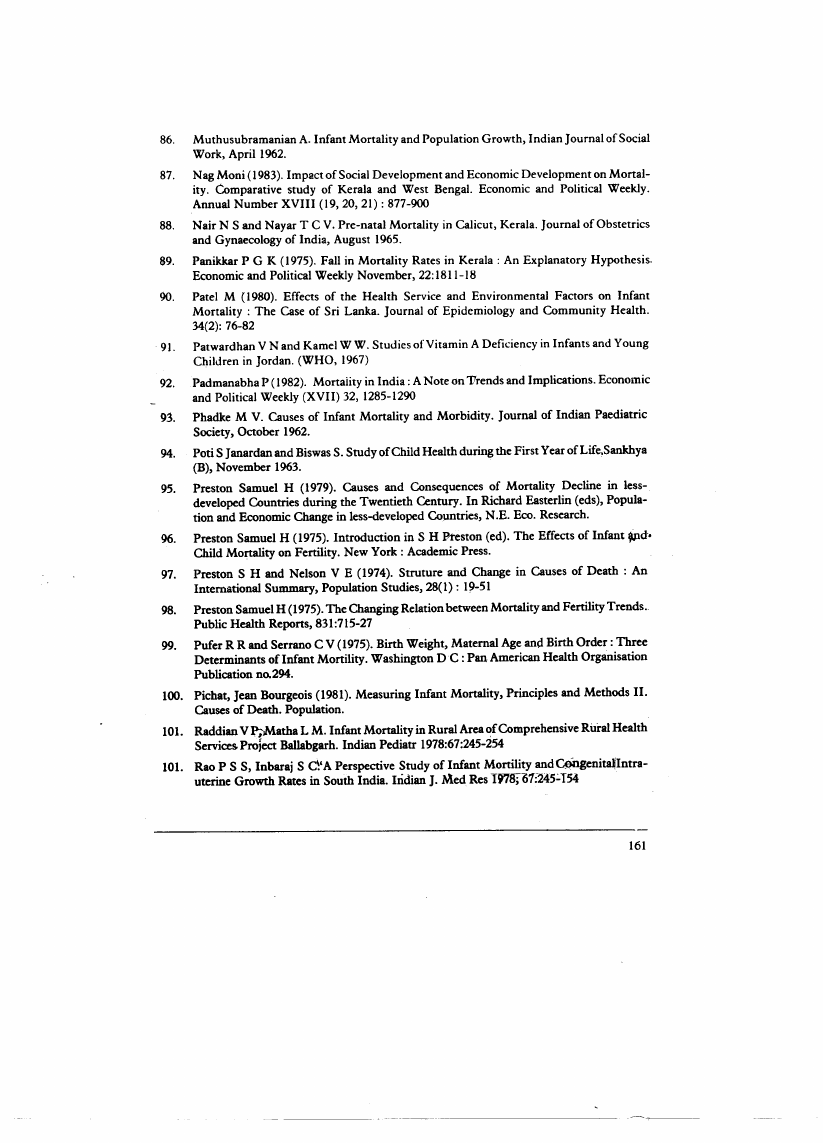

17.1 Page 161 |

▲back to top |

|

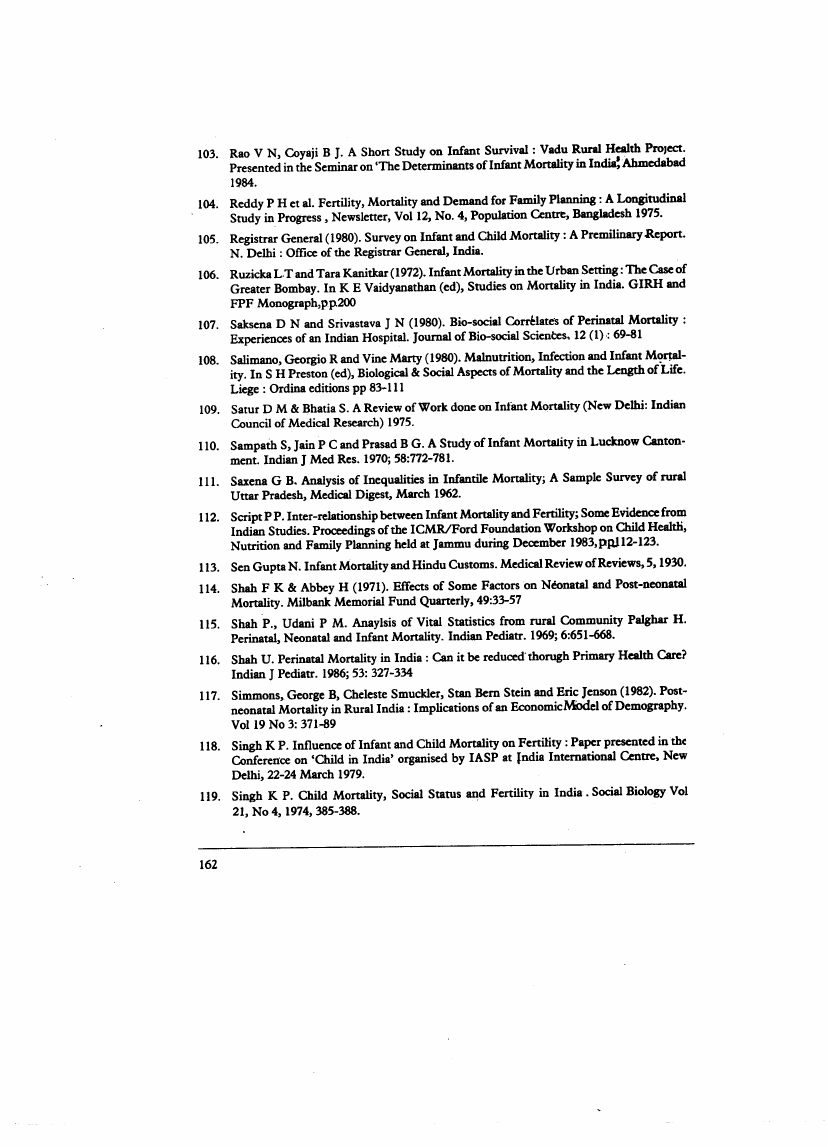

17.2 Page 162 |

▲back to top |

|

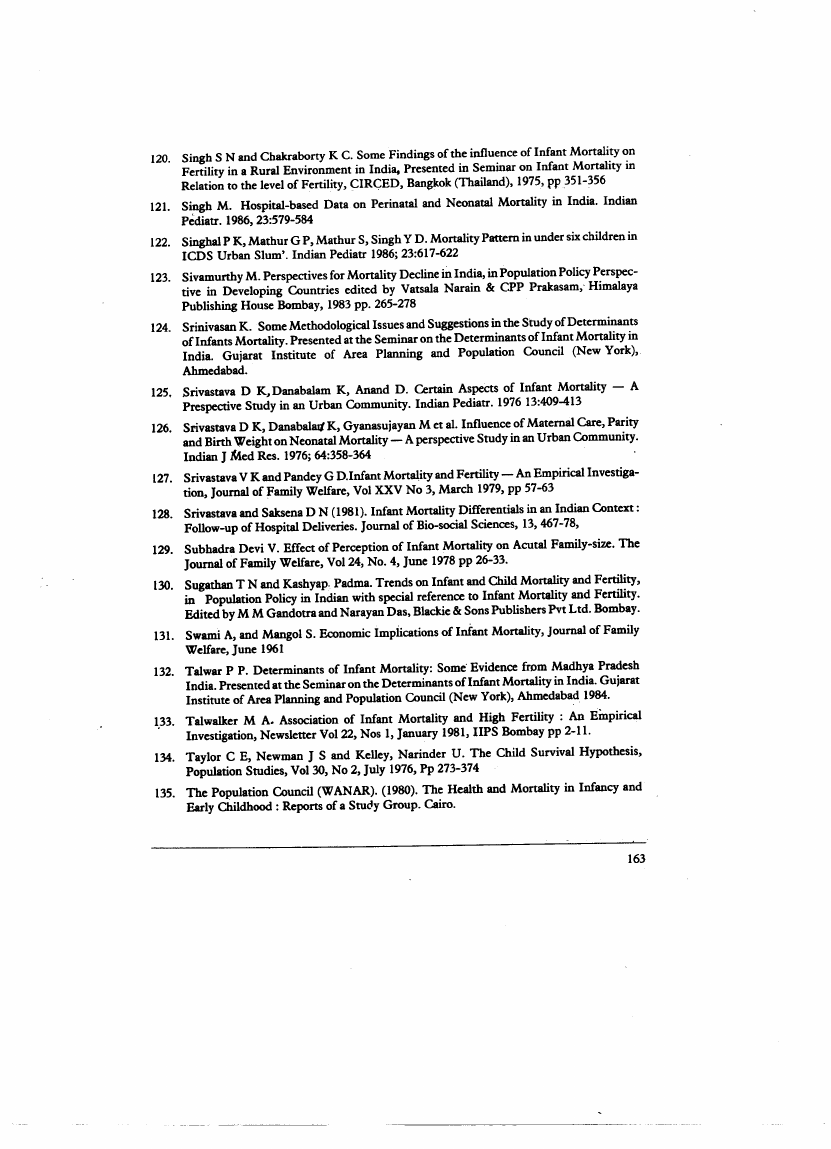

17.3 Page 163 |

▲back to top |

|

17.4 Page 164 |

▲back to top |

|

17.5 Page 165 |

▲back to top |

|

17.6 Page 166 |

▲back to top |

|

17.7 Page 167 |

▲back to top |

|

17.8 Page 168 |

▲back to top |

|

17.9 Page 169 |

▲back to top |