|

People Show the Way |

|

1 Pages 1-10 |

▲back to top |

|

1.1 Page 1 |

▲back to top |

|

1.2 Page 2 |

▲back to top |

|

1.3 Page 3 |

▲back to top |

|

1.4 Page 4 |

▲back to top |

|

1.5 Page 5 |

▲back to top |

|

1.6 Page 6 |

▲back to top |

|

1.7 Page 7 |

▲back to top |

|

1.8 Page 8 |

▲back to top |

|

1.9 Page 9 |

▲back to top |

|

1.10 Page 10 |

▲back to top |

|

2 Pages 11-20 |

▲back to top |

|

2.1 Page 11 |

▲back to top |

|

2.2 Page 12 |

▲back to top |

|

2.3 Page 13 |

▲back to top |

|

2.4 Page 14 |

▲back to top |

|

2.5 Page 15 |

▲back to top |

|

2.6 Page 16 |

▲back to top |

|

2.7 Page 17 |

▲back to top |

|

2.8 Page 18 |

▲back to top |

|

2.9 Page 19 |

▲back to top |

|

2.10 Page 20 |

▲back to top |

|

3 Pages 21-30 |

▲back to top |

|

3.1 Page 21 |

▲back to top |

|

3.2 Page 22 |

▲back to top |

|

3.3 Page 23 |

▲back to top |

|

3.4 Page 24 |

▲back to top |

|

3.5 Page 25 |

▲back to top |

|

3.6 Page 26 |

▲back to top |

|

3.7 Page 27 |

▲back to top |

|

3.8 Page 28 |

▲back to top |

|

3.9 Page 29 |

▲back to top |

|

3.10 Page 30 |

▲back to top |

|

4 Pages 31-40 |

▲back to top |

|

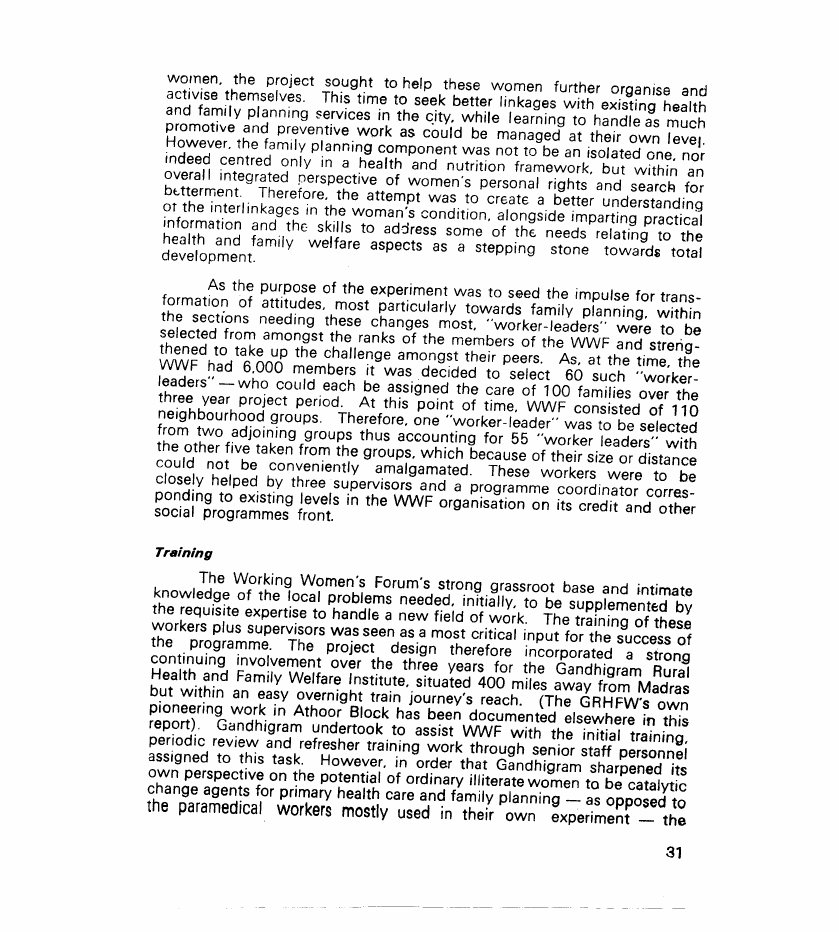

4.1 Page 31 |

▲back to top |

|

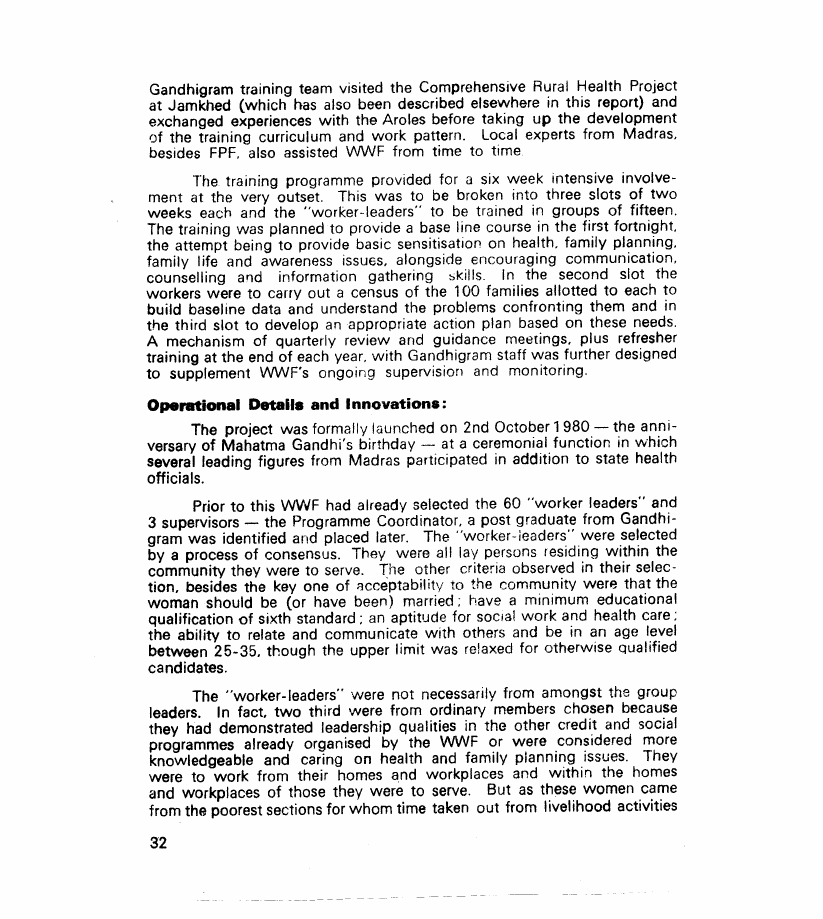

4.2 Page 32 |

▲back to top |

|

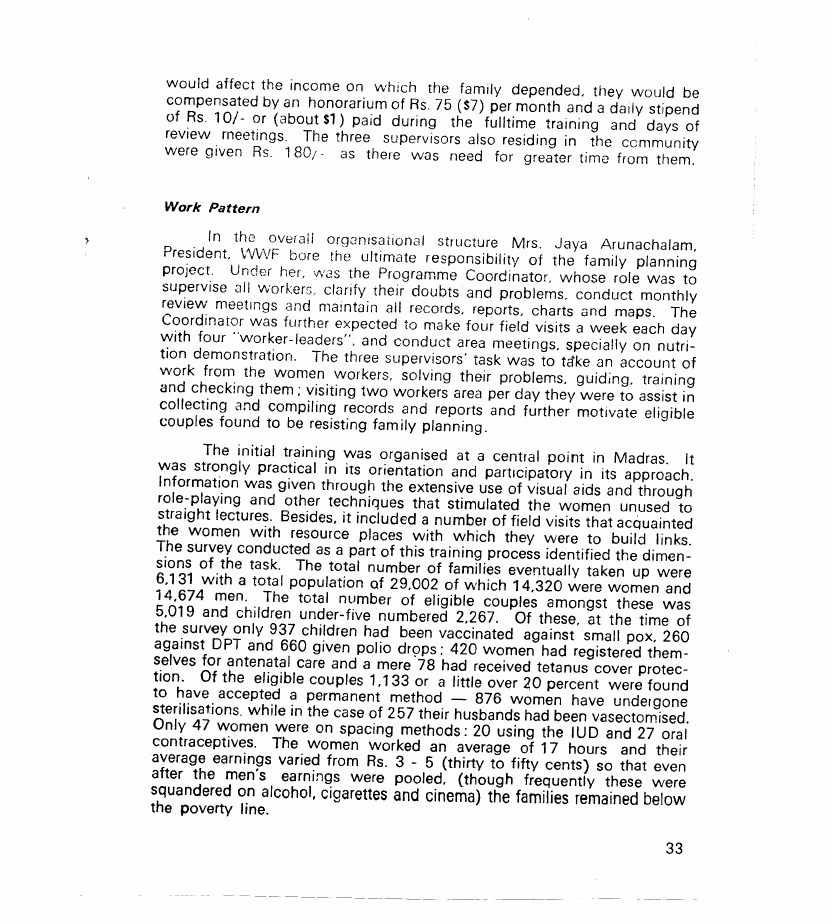

4.3 Page 33 |

▲back to top |

|

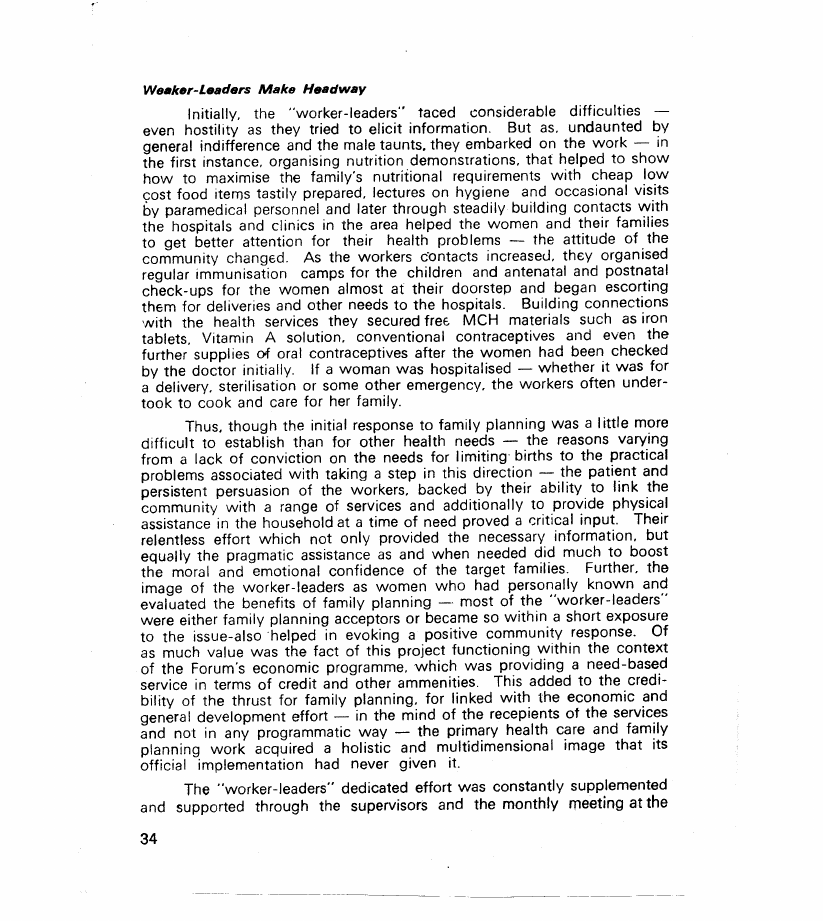

4.4 Page 34 |

▲back to top |

|

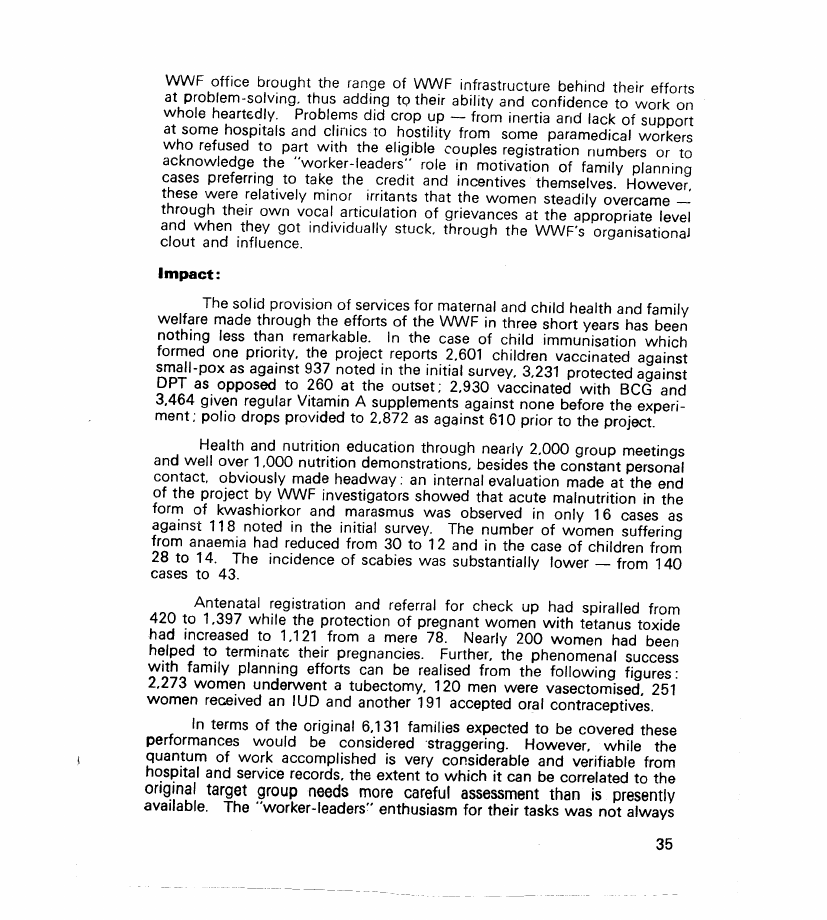

4.5 Page 35 |

▲back to top |

|

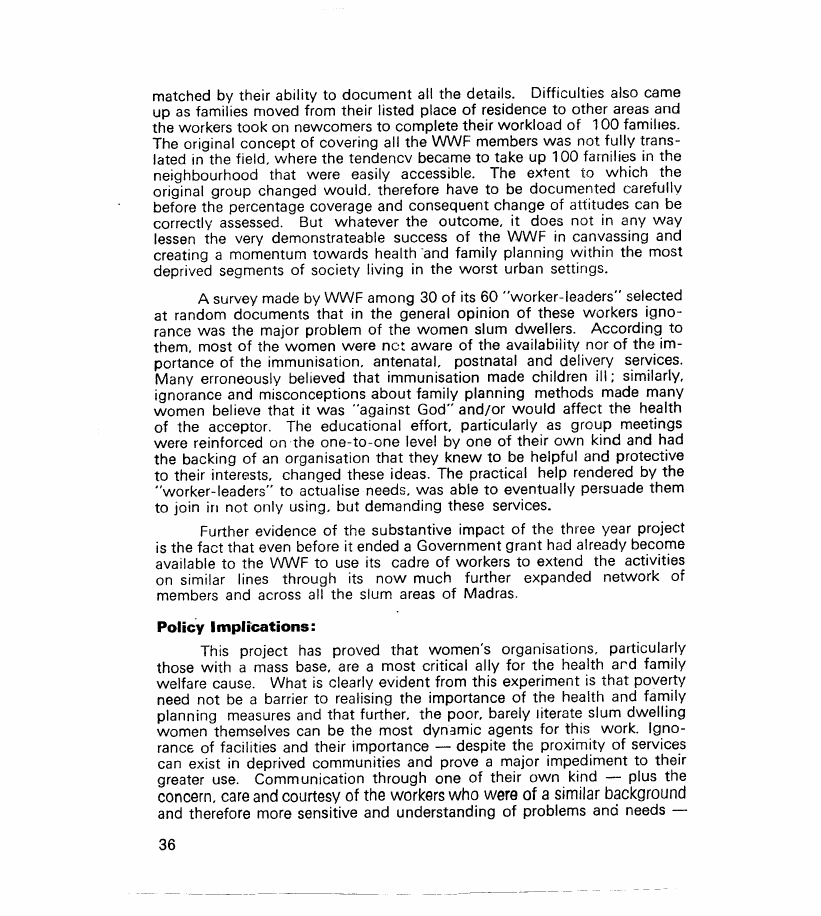

4.6 Page 36 |

▲back to top |

|

4.7 Page 37 |

▲back to top |

|

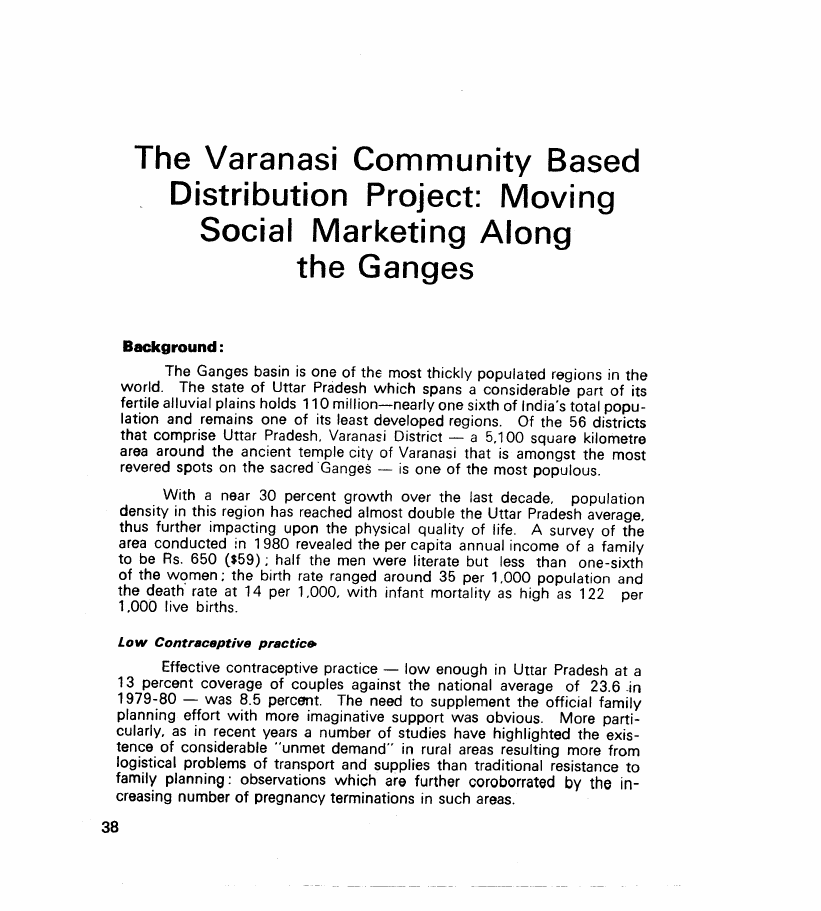

4.8 Page 38 |

▲back to top |

|

4.9 Page 39 |

▲back to top |

|

4.10 Page 40 |

▲back to top |

|

5 Pages 41-50 |

▲back to top |

|

5.1 Page 41 |

▲back to top |

|

5.2 Page 42 |

▲back to top |

|

5.3 Page 43 |

▲back to top |

|

5.4 Page 44 |

▲back to top |

|

5.5 Page 45 |

▲back to top |

|

5.6 Page 46 |

▲back to top |

|

5.7 Page 47 |

▲back to top |

|

5.8 Page 48 |

▲back to top |

|

5.9 Page 49 |

▲back to top |

|

5.10 Page 50 |

▲back to top |

|

6 Pages 51-60 |

▲back to top |

|

6.1 Page 51 |

▲back to top |

|

6.2 Page 52 |

▲back to top |

|

6.3 Page 53 |

▲back to top |

|

6.4 Page 54 |

▲back to top |

|

6.5 Page 55 |

▲back to top |

|

6.6 Page 56 |

▲back to top |

|

6.7 Page 57 |

▲back to top |

|

6.8 Page 58 |

▲back to top |

|

6.9 Page 59 |

▲back to top |

|

6.10 Page 60 |

▲back to top |

|

7 Pages 61-70 |

▲back to top |

|

7.1 Page 61 |

▲back to top |

|

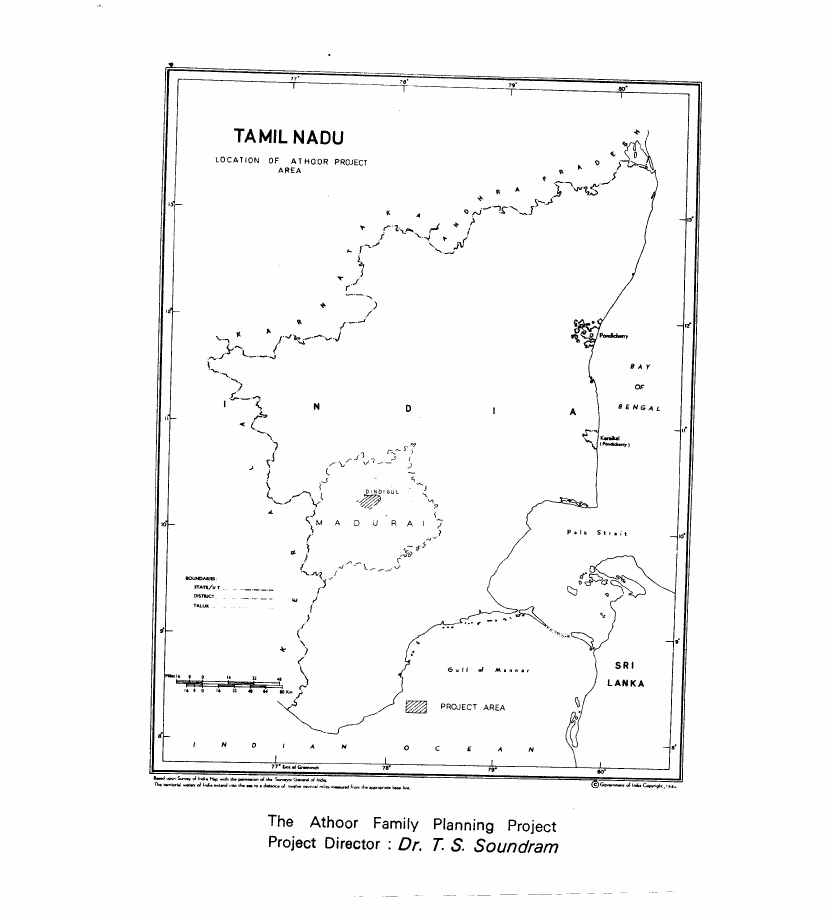

7.2 Page 62 |

▲back to top |

|

7.3 Page 63 |

▲back to top |

|

7.4 Page 64 |

▲back to top |

|

7.5 Page 65 |

▲back to top |

|

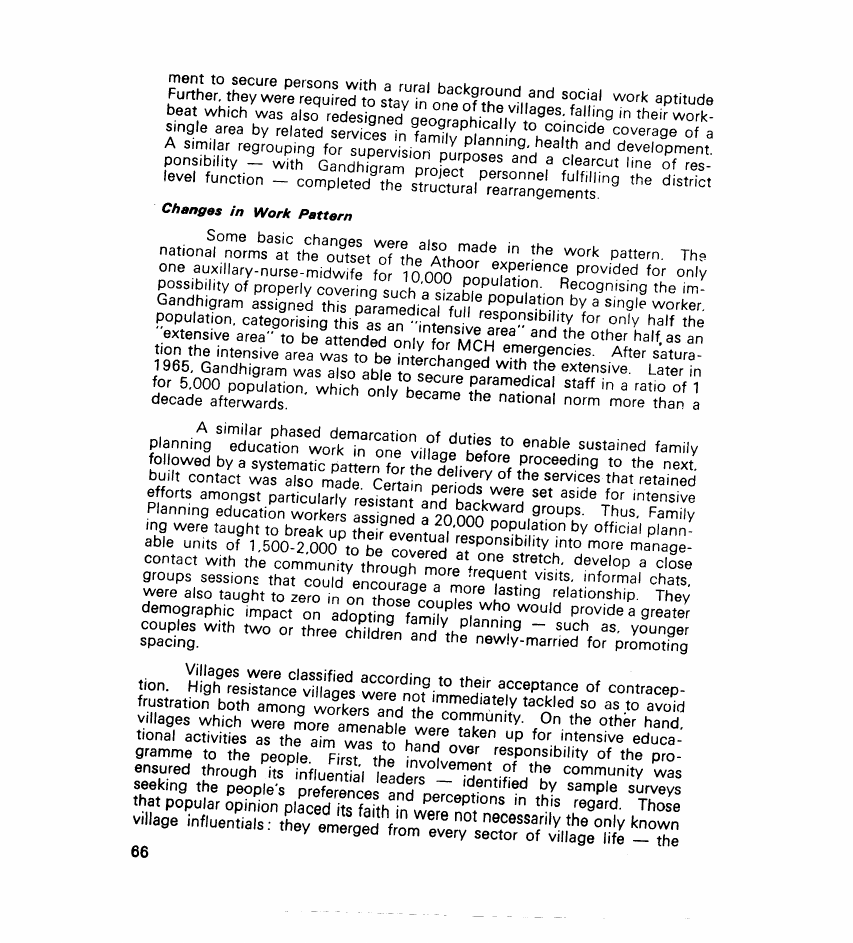

7.6 Page 66 |

▲back to top |

|

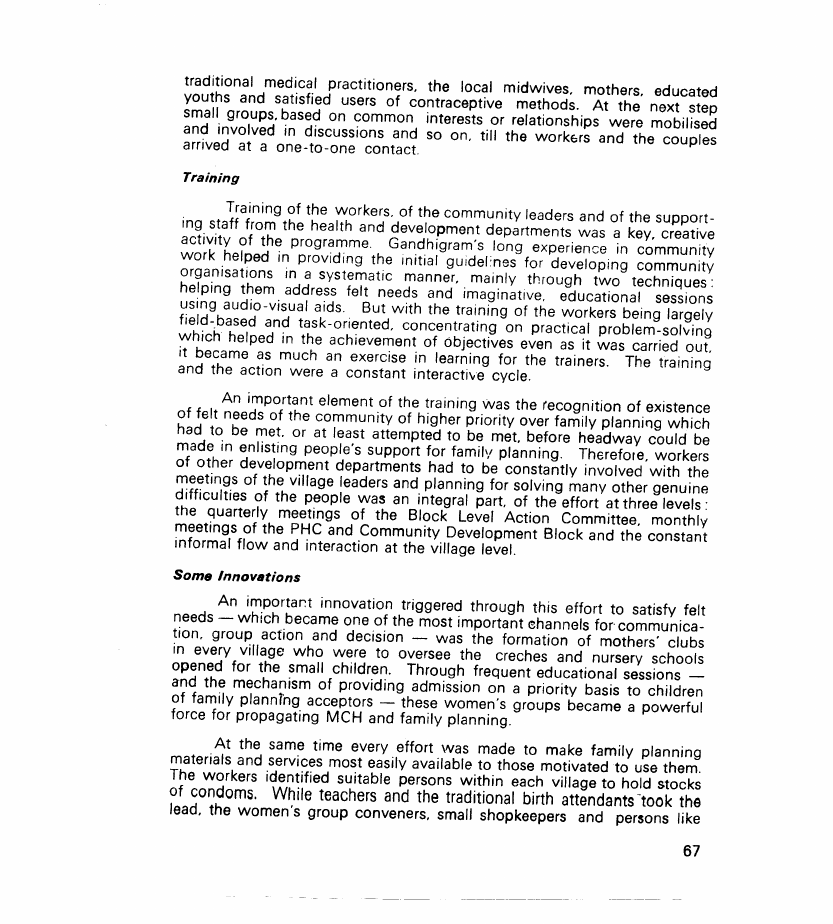

7.7 Page 67 |

▲back to top |

|

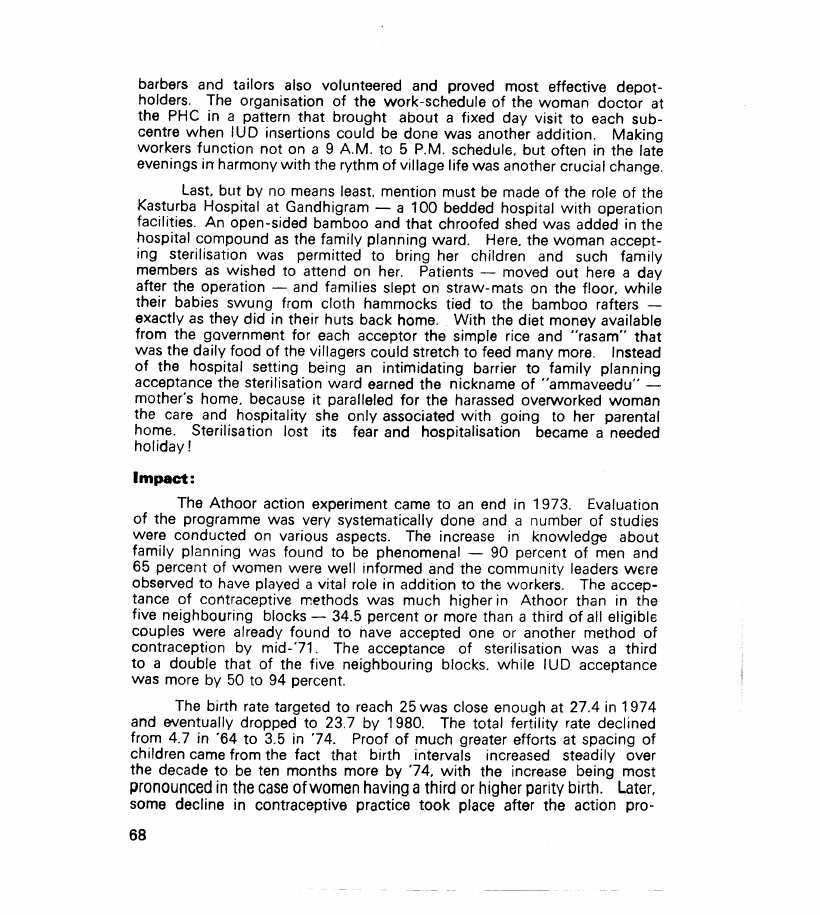

7.8 Page 68 |

▲back to top |

|

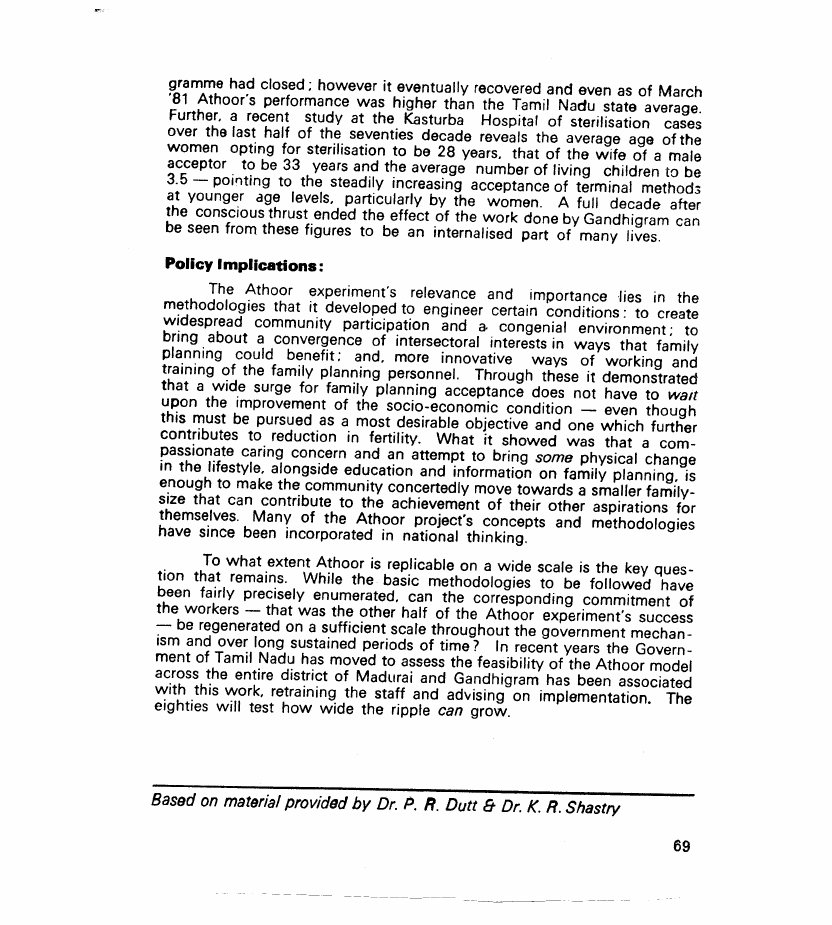

7.9 Page 69 |

▲back to top |

|

7.10 Page 70 |

▲back to top |

|

8 Pages 71-80 |

▲back to top |

|

8.1 Page 71 |

▲back to top |

|

8.2 Page 72 |

▲back to top |

|

8.3 Page 73 |

▲back to top |

|

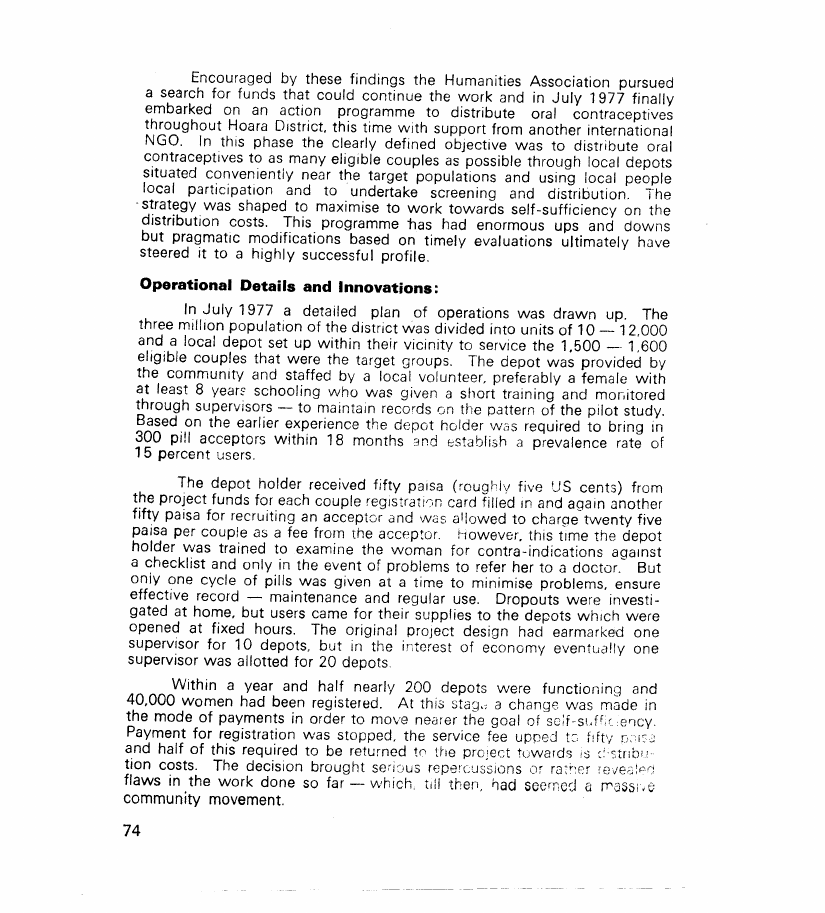

8.4 Page 74 |

▲back to top |

|

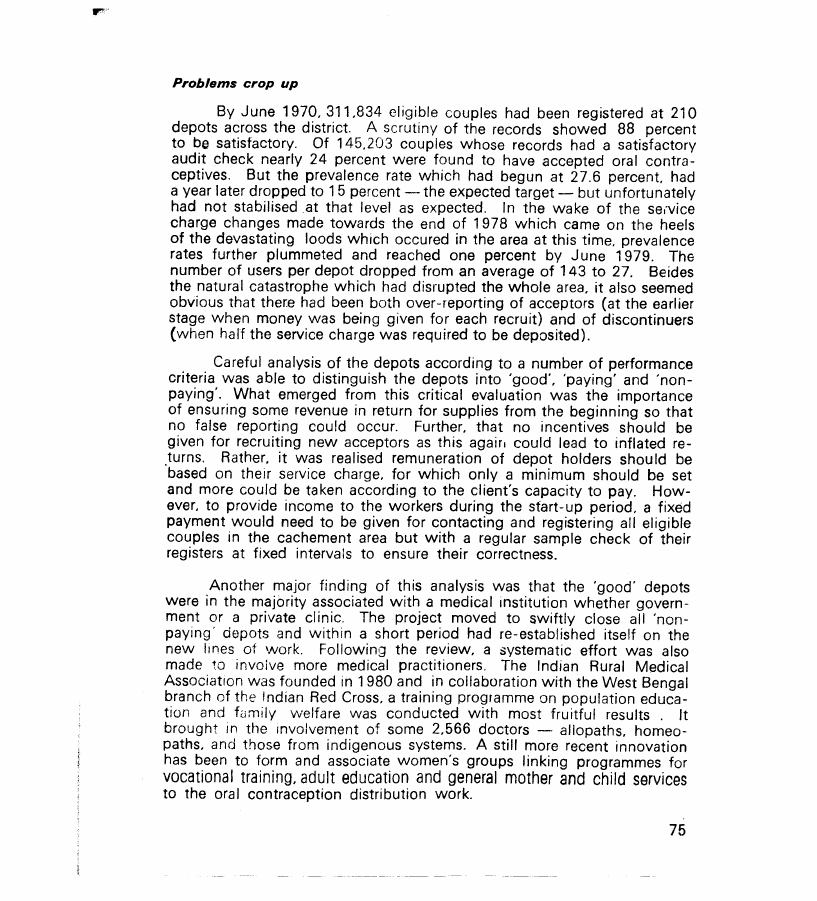

8.5 Page 75 |

▲back to top |

|

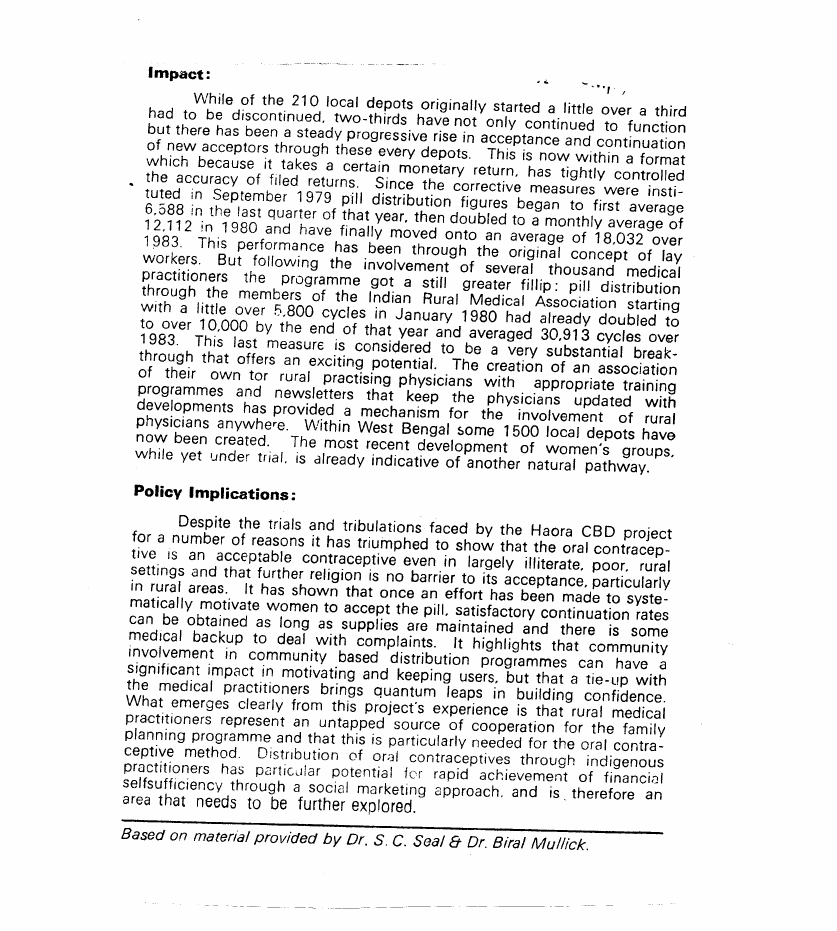

8.6 Page 76 |

▲back to top |

|

8.7 Page 77 |

▲back to top |

|

8.8 Page 78 |

▲back to top |

|

8.9 Page 79 |

▲back to top |

|

8.10 Page 80 |

▲back to top |

|

9 Pages 81-90 |

▲back to top |

|

9.1 Page 81 |

▲back to top |